Chapter 7 Module 4: Core Issues on Development

Figure 7.1: L’Hypnose, Lubumbashi DRC (2018)

In previous sessions, we have examined what development is and the general context that has set the ground to the current conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa. We now know that development goes beyond economic growth and that it is multidimensional. In the previous Module, we examined how history and the political background can impact development in the region.

In this Module, we will look at how different economic activities affect and promote development and provide opportunities to improve the population’s livelihoods.

Topics Covered:

- Structure of the economy: Agriculture; industrial policy

- International trade

- Investment and financial development

- Foreign aid

7.1 Structuring the Economy

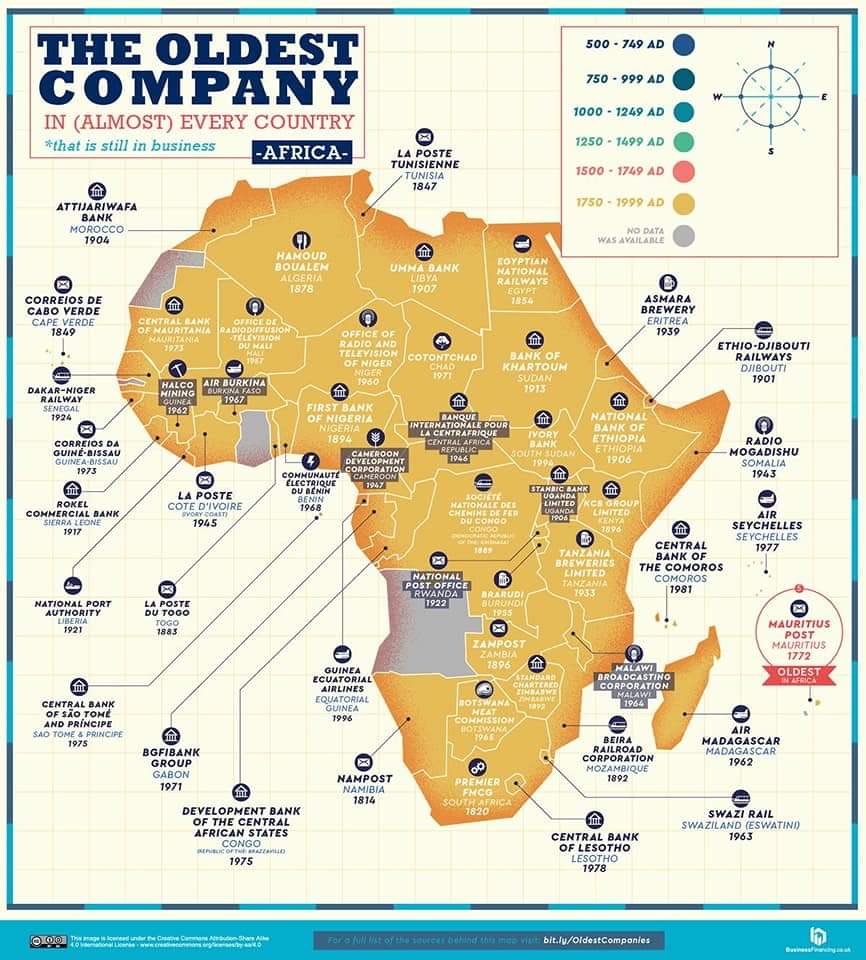

Figure 7.2: Source: Ghosh, I. (2020) https://www.visualcapitalist.com/oldest-companies/

According to the Neoclassical growth theory, two central elements support economic growth: capital per worker and technological innovation.

When we talk about capital per worker, there are two important definitions.

Capital, which refers to the assets (or instruments) that can allow us to perform our tasks. These tools can be as simple as an arrow used by a hunter, or as sophisticated as a complex machine.

These tools are used by workers, which correspond to the persons who participate in the economy’s production side. The amount of workers that a country has depends on its population and its age structure.

Technological innovation refers to processes that make us more productive. It helps us to produce more with the tools and workers that we have. This is one of the critical concepts in growth theory. How do countries become more productive is an essential question in macroeconomics, and it is one of the hardest ones to answer. However, there are a few ideas that we will see in class that can help us to, partially, respond to this.

7.1.1 Agriculture

Half of the world’s land is used for agriculture, according to Our World in Data (2019). Although the share of the population that works in agriculture has steadily decreased in many parts of the world, it is still the source of employment of large shares of the working population in low-income countries.

Can agriculture be a source of development? If you remember, the Green Revolution referred to the set of policies implemented to solve famine and find ways to feed a rapidly increasing world population. This led to the adoption of high-yield crop varieties (HYV), mostly in Latin America and Asian countries12. In general, the adoption of these HYV led to a rapid increase in productivity. A paper from 2018 by Gollin, Worm Hansen, and Wingender finds that at least part of East Asia’s rapid growth could have come from HVY adoption. The authors find that, over a sample of 84 countries, a ten percentage points increase in HYV adoption increased GDP per capita by about 15 percent.

Thus, the Green Revolution led to important innovations for developing countries. However, as mentioned before, it also had unintended consequences, such as an increase in inequality (remember the case of Mexican farmers?), and certain practices are not suitable for small farmers 13. In economics, we would think about sustainable agriculture as the practice that would promote development for the population today and for future generations.

In that regard, how can agriculture support development, ensure food security, and reduce poverty? Is it possible to improve agricultural productivity (particularly, small-holder agriculture, which is the most common in Sub-Saharan Africa) while at the same time avoiding soil erosion and ensuring adequate livelihoods for agricultural producers?

Some general issues on agriculture and development

Property rights Economists have traditionally emphasized the need to secure property rights to promote well-functioning markets. By doing so, land will be devoted to more productive uses. Although this is true for every sector in the economy, the effects of property rights on agricultural productivity have gained much attention. However, in different regions, property rights are defined differently, and they do not always emerge from formal (government) sources. Thus, the question is: what property rights? Chari et al. (2017) argue that formalizing property rights is critical to ensure the productivity of the sector in the case of China. The authors explore a rural land reform that took place in China in 2003 that ‘increased legal protections for land contracts and granted farmers legal protections for leasing contracts over agricultural land’ (Chari et al., 2017). This finding goes in line with Studwell’s (2013) argument, who argues that land reform was at the source of the development in Northeast Asia, increasing agricultural productivity and funding the industrialization of other areas.

In Latin America, however, there has been no significant land reform, and this may be at the source of low agricultural productivity in the region (Kay, 2002) leading to a further agglomeration of land in the hands of political and economic elites (remember the case of Mexico). Therefore, there is endogeneity between land reform and land agglomeration (Evans, 2020).

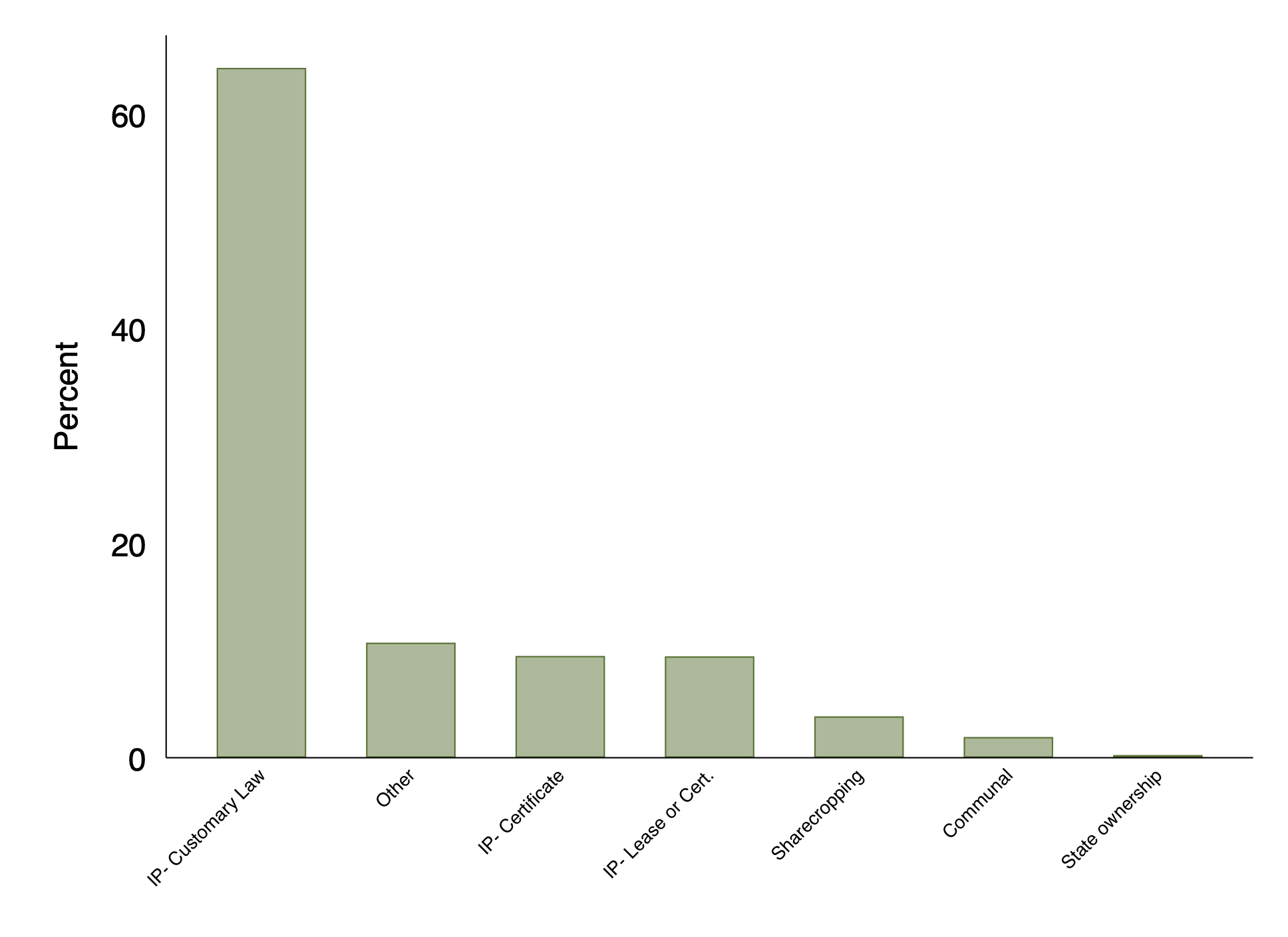

In Sub-Saharan Africa, however, property rights’ configuration is different, and ensuring what property rights are accepted may be a challenge. For instance, a small-holder farmer survey in 2016 in the Ivory Coast asked for the form of land ownership that they held. The responses are included in the graph below. From a total of 5,706 farmers, more than 60% confirmed that their land rights had been issued by a customary chief, whereas less than 20% had property rights issued by the government.

Figure 7.3: Source: CGAP Survey, CDI (2016)

Agricultural extension programs One way to improve the productivity of agriculture and ensure that the sector improves the well-being of producers is by helping the sector attain its potential. This requires the adoption of better agricultural practices, such as fertilizers or combining different crops. However, there is a fragile line between what will help the farmers and what could distort the local markets. For instance, maximizing yields do not always translate into maximizing profits for farmers, as Caldwell et al. (2019) explain from a study they did on different programs that have taken place in Africa. Thus, as the authors found, information needs to be tailored to adapt to the different needs of farmers and be accessible to them. This can help solve information asymmetry issues that are very common in the sector and reduce its possibilities of fighting poverty.

Trade Although we will touch more about this in a future topic in this Module, globalization has also brought challenges to the development of agriculture in low- and middle-income countries. First, most of the time, farmers are price-takers, whereas the prices are set in the international markets. Farmers receive just a small portion of what these prices are, as there are multiple intermediaries (this is mostly clear for commodities such as coffee or cocoa). Dhingra and Tenreyro (2017) find that creating value chains at home (agribusinesses) could increase the prices received for the case of Kenya. This is because agribusinesses provide farmers with technical support, or they serve as credit collaterals. However, as world prices increase, the gains for farmers become lower, as their investments also increase to keep up with the necessary productivity in markets that are not fully developed.

Related to that is the role that governments play to support farmers. Although government intervention has been high in African countries’ agricultural sector, this has not led to gains in productivity, as agriculture has been used to subsidize industrial development (and patronage). Since the 1990s, tariffs and government intervention have decreased in low-income countries, whereas high-income countries in the West have kept the massive subsidies for farmers, increasing the productivity disparities across places and limiting the terms of trade of low-income countries.

Gender Gender is a crucial dimension to explore when examining agriculture, as around 40% of the labor in farm production is female. (Palacios et al., 2016). However, even if this is the case, many inequalities would have to be addressed to ensure more equitable and productive development.

One of these inequalities is related to land ownership, as women are less likely to own land. For instance, in the CGAP Survey in the Ivory Coast, 89% of land tenants are men, and female landowners tend to be poorer than male landowners. In Ghana, women participate in many cocoa production stages, but they do not participate in the sale process of the crop, as it is an activity devoted to men. This has to do with cultural practices, but it is also related to women’s lower literacy levels. The outcome is that this reduces the bargaining power of women and their development opportunities.

7.1.2 Industrial Policy

Industrial policy has been vital for rapid economic growth. In East Asia, for example, the transformation from agrarian societies to industrial hubs was fast and successful, moving from labor-intensive production to heavy industries to capital-intensive industries (Evans, 2020).

However, this ‘East Asian Miracle’ has not been replicated in other developing regions, and many have questioned if industrial policies were at the bottom of the rapid development in these areas. Lane (2017) examines this question using the case of South Korea’s industrial push in the Heavy Chemical and Industry (HCI). He finds that the policy created lasting effects in targeted industries, which was supported by investment in capital and by allowing to import key inputs. However, the study recognizes its limitations as it does not look into the political economy costs of this initiative and the societal costs it generated.

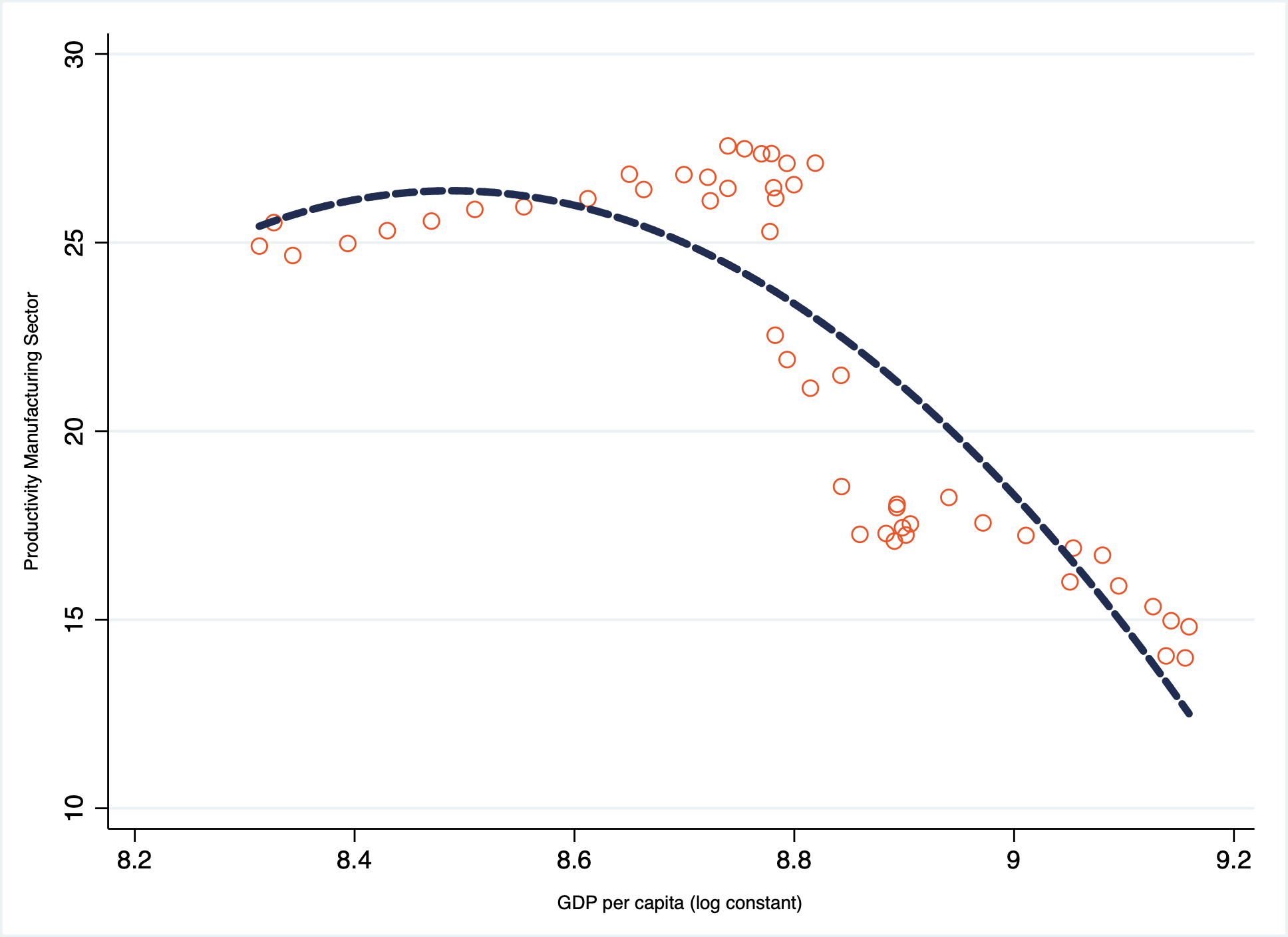

This is similar to what other authors have found. Mainly, Latin American countries did not succeed in their efforts to industrialize fully, and there has been a deindustrialization process. Rodrik (2016) argues that globalization has been at the source of this process, as Latin American countries could not gain a comparative advantage before opening to international trade, which led to a decrease in the participation of the manufacturing sector in GDP.

Figure 7.4: Deindustrialization Latin America

Can we envision a successful industrial transformation in African countries? Although there has been a transition from the rural to the urban sector, workers move towards the services sector. According to Newman et al. (2016), Africa faces a “manufacturing deficit” that could harm its development. This is a controversial issue, as there are many different definitions of what industrialization is and how to get there (Oqubay, 2015). Besides, whereas neoclassical economics thinking supports low state-intervention to prevent market distortions, some scholars argue the importance of a state-led development that prioritizes some sectors over others.

However, how well this practice works depends on the specific country context. In the case of Nigeria, for instance, Kohli (2004) argues that sponsoring industrialization in a neo-patrimonial state led to a failed economic transformation, as state elites focused on keeping power and privatizing resources for personal gain. This impeded the formation of a robust industrial formation without effective state intervention. This is contrary to what happened in developmental states in Asia, which were able to separate themselves from personal interests (Kohli, 2004; Oqubay, 2015, Rodrik 1995).

However, some areas of opportunity exist. Oqubay (2015) introduces the case of Ethiopia, a latecomer in the development process that has been able to rapidly grow sustained by a rapid industrialization process.

This is not to say that structural challenges have disappeared on the continent. Using industrialization as a tool for development requires to look at specific factors, such as institutions, infrastructure, human capital, and even geography. Nevertheless, even in landlocked countries, such as Ethiopia, there may be certain elements that could make industrialization a tool for development in Africa, especially if the state can limit the intervention of private interests.

7.2 International Trade

Is international trade good for development? Neoclassical trade models argue that trade is a path for development. It allows producers to expand their markets, whereas consumers can enjoy lower prices and higher product diversity. Countries can focus on their comparative advantage and improve economic efficiency. This explains why, as part of the structural adjustment programs implemented in the Global South during the 1980s-1990s, a series of reforms aimed at reducing trade barriers were implemented.

However, applying these models to examine developing countries requires some caution. There are very large differences in the economic environments of these countries and high-income countries, which could lead to different conclusions for these countries.

In general, there are different visions of trade and development:

Trade expands imperialism that leads to exploitation and expropriation: Suwandi (2019) argues that global commodity chains lead to unequal power relations between employers and workers that are located in different extremes of the world. Suwandi states that the maximization of profits view of capitalism leads to an unequal exchange based on a hierarchy of wages. In addition to this, trade openness in weak states may lead to worsening conditions in areas such as pollution and child labor, leading to a ‘race to the bottom’ by pushing for reallocations of labor and capital, as shown by Rodrik (2018) and Chaudhuri et al. (2006)14. In markets with imperfect information, the costs of trade may be exacerbated. At least this is what is shown by Atkin (2016), who finds that, in Mexico, opportunities in the export manufacturing sector lead to lower school acquisition of working-age youths. Jensen (2010) and Atkin and Khandelwal (2019) argue that this may be because they may lack information about the long-term costs of lower school acquisition.

Trade leads to economic development: Scholars that promote this view argue that, by improving local conditions, trade will be generally beneficial for low- and middle-income countries. Irwin (2019), for instance, finds that, in a cross-country analysis, lower tariffs lead to “improved productivity performance”.

It depends. The effects of trade depend on how frictions between trade and institutions are addressed: Having weak institutions leads to measures that are not well implemented. For instance, for the case of protectionist measures, Sequeira and Djankov (2014) show that, for the case of Mozambique, there exist tariff evasions that lead to more open markets than predicted. Nevertheless, the incertitude of how different measures will be implemented, also reduces the possibilities to maximize trade gains, as shown by Nunn (2017).

This perspective argues that the benefits of trade are more substantial in stronger institutional context. However, trade also has the potential to improve institutions’ quality, as argued by Nunn and Trefler (2014).

Different versions of this view also point out that international trade generates winners and losers in every country participating in it (Pavnick, 2017). This is because changes in prices will lead to changes in income distribution. Pavnick (2017) argues that the effects of trade are usually intertwined with the effects of other domestic policies and that the final effects are context-specific. Overall, the author finds that trade has increased inequality. Something similar is shown by Dragusanu and Nunn (2018). They show that fair trade, a certification that ensures that producers are paid a fair price for their product, generates mixed effects. It is beneficial to farm owners and skilled workers but has no effects on hired unskilled workers and intermediaries.

Therefore, as we can see and we will discuss in class, we cannot generalize about the effects of trade on the development of low- and middle-income countries, since many factors need to be taken into account and there are many dimensions in the debate. But this provides a useful lesson the need to contextualize and not ‘over-generalize’ and find the mechanisms behind the different findings.

7.3 Investment

Investment is key to promote economic development, as it is the source of funds to increase capital and accelerate technological innovation. There are two main types of investment:

- Direct investment in Capital

- Investment in financial markets

In an open-market, investment sources are not restricted to the funds that local savers can provide. Instead, once markets open, these funds can come from other countries. This is what we know as:

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

- Foreign portfolio (or financial) investment

7.3.1 Foreign Direct Investment

FDI is one of the most important sources of capital. The motivations behind the decision of companies to invest in a certain country, as well as the benefits for the host country have been largely studied. In general, the agreement in economics is that there are clear and important benefits generated by FDI, but these are constrained by the ability of the host country to absorb them and spread them across different economic sectors.

7.3.2 Financial Markets

One of the barriers towards development is the lack of access to financial markets that the poor face. It impedes entrepreneurship, and it also prevents investment in more productive alternatives. It also increases the poor’s vulnerability, as they lose the mechanisms to cope with natural disasters, pests, or other emergencies.

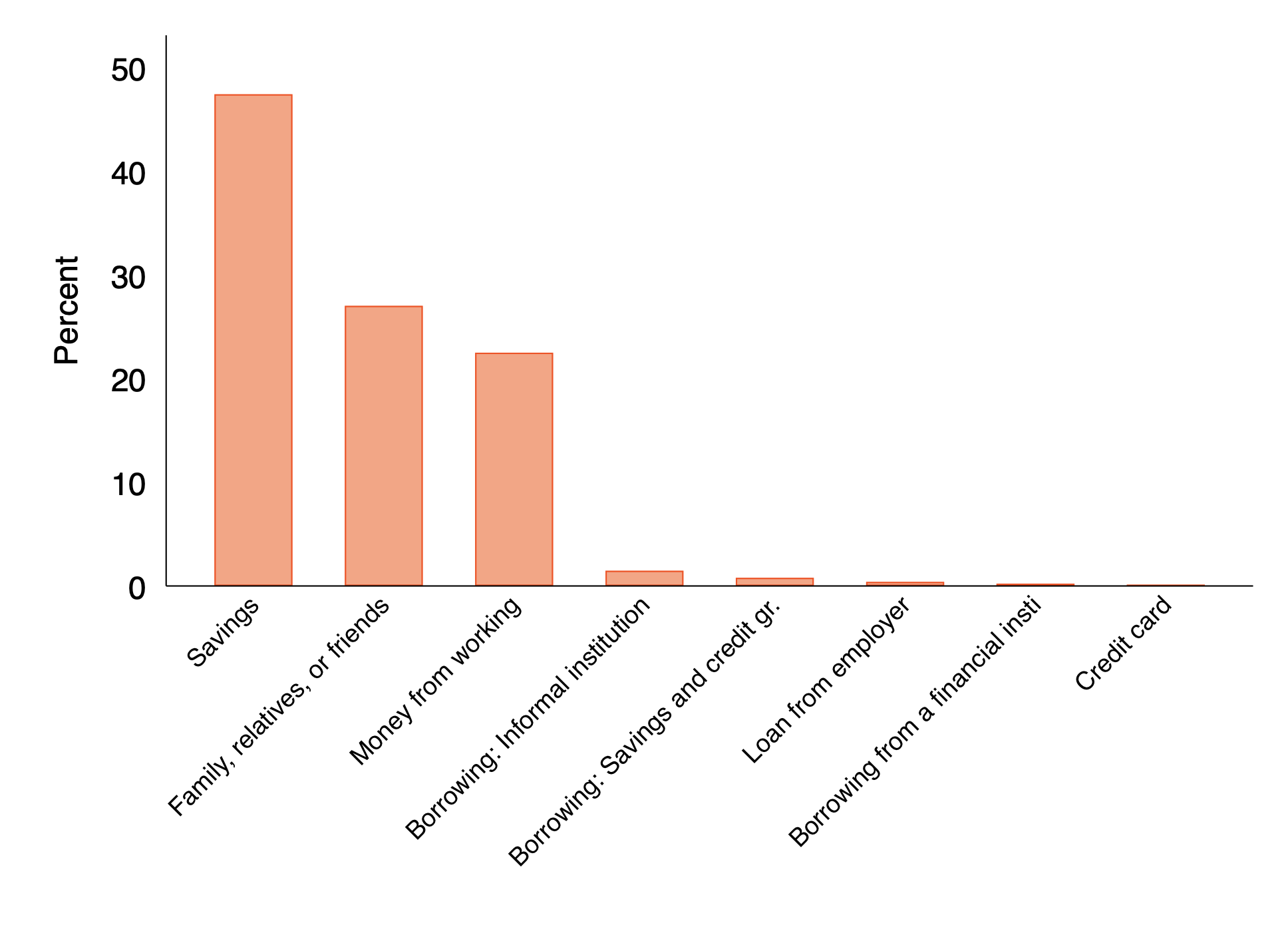

In Côte d’Ivoire, for instance, a survey conducted among small farmers asked them about the possibility of obtaining 44,000 CFA Francs (USD 79.43) within a month if they had to face an emergency. 63.78% expressed that it was either very or somewhat possible, whereas 36.22% expressed that it was impossible. Of those that mentioned that it was at least somewhat possible to obtain the money, only 2.53% named either a formal or an informal financial institution as the source of the funds.

Figure 7.5: CGAP CDI (2016)

In addition to this, as explained by Toochi Aniche (2020), there is a high financial cost linked to remittances due to the weak financial system that exists in many low- and middle-income countries. This leads to the use of informal channels to send those remittances.

Recently, new forms of financial markets have been introduced to facilitate financial transactions across the population in African countries. These channels seek to reduce the costs of entry and the system’s complexity, bringing financial services to the general population, and promoting development. These tools also have the objective of avoiding potential issues of corruption by reducing the number of intermediaries in the local financial system.

Other systems that also seek to reduce intermediaries and corruption have been introduced in other parts of the world. This is the case, for instance, of Smartcards in India, which are biometrically-authenticated payments that delivered payments of a cash transfer program to beneficiaries, without having to rely on intermediaries. The program was evaluated by Muralidharan, Niehaus, and Sukhtankar (2014), who found a significant reduction in leakage of funds in the process.

7.3.3 The private sector

In this section, we will examine some issues related to the business environment that impact the development of low- and middle-income countries.

One of the main topics related to the business environment in low- and middle-income countries is public finance. Why? Because in large degree, weak taxation and low levels of formal activity limit the potential development of low- and middle-income countries. A large informal sector limits the capacity to create decent sources of employment (Aly Mbaye, 2019)

What is behind weak levels of taxation? There are multiple reasons. The first one is that some low- and middle-income countries have relied on rents obtained from selling commodities (minerals, oil, agricultural products). In the meantime, the growth of other formal activities largely depends on the business environment, which is filled with high costs and bureaucracy that is often corrupt or complex (Mbaye and Gueye 2018).

Besides, to tax requires capacity, and to build that capacity requires effort. Therefore, governments will tax those that are easier to tax. This is why the consumption tax (VAT) is so important in low- and middle-income countries. It is easier to collect this tax as it is paid at the moment of the transaction. However, other types of taxes are harder to collect, leading to some concerns about tax progressivity. Besides, if governments do not use these taxes to deliver public goods, taxpayers may see less inclined to pay taxes.

Currently, the informal sector is the primary source of employment in Sub-Saharan Africa. These jobs are characterized by: informally paid employees without social security, paid employees in unregistered enterprises, self-employees in unregistered enterprises, employers in unregistered enterprises, and family workers (ILO 2003; Shehu and Nilsson 2014). These firms, for their configuration, have limited capacity to grow and are therefore not very productive.

Tax avoidance

Tax avoidance refers to the use of laws and legal mechanisms to minimize the amount of tax paid to the authorities. Although legal, these methods remain quite dubious in ethical terms and often are on the verge of legality. They hurt the development of every country where the practices are conducted and compromise the development sustainability of low- and middle-income countries. Ocampo (2019) states that developing countries lose at least $100 billion, hidden by companies in tax havens. Zucman (2016) argues that tax avoidance diverts 40% of foreign profits from multinationals. Ocampo (2019) also argues that, whether most countries have to deal with this issue, low- and middle-income countries are more resource-constrained.

The OECD has pushed for reforms, including imposing a global corporate tax of 25%. Some countries (including low- and middle-income countries) fear that this would lower foreign direct investment. However, this would remove the existence of tax havens, which are those countries with zero or little tax rates to foreign entities.

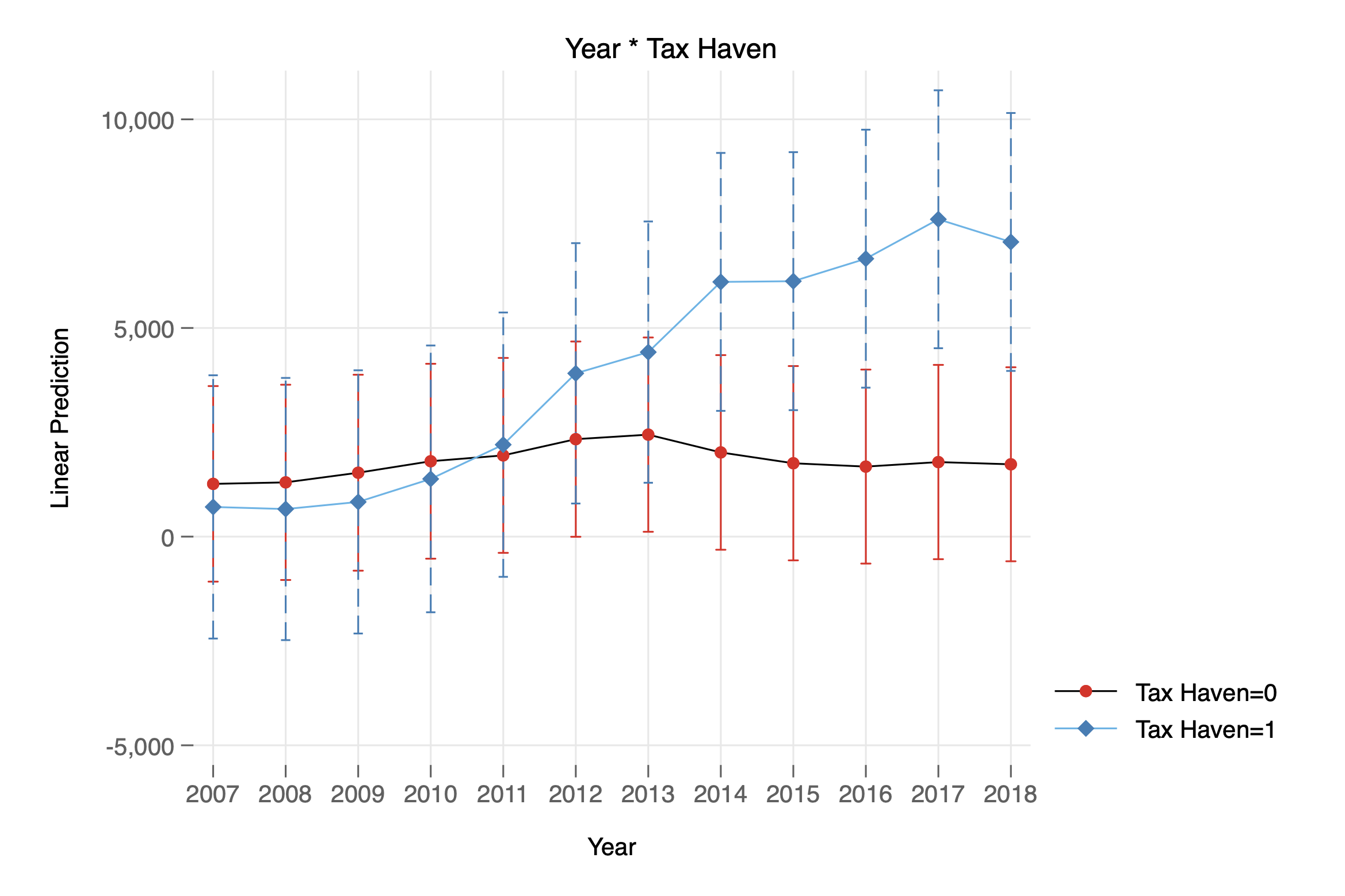

To examine how this affects developing countries, the next image shows the linear prediction of Brazilian investment in tax havens and other countries. As you can see, Brazilian firms send funds to entities in these countries. The main channel for this transfer is profit shifting. In this transfer, firms buy items at higher-than-normal prices from affiliates located in low-tax countries. This reduces the profits of the Brazilian firms, and thus the taxes they pay.

Figure 7.6: Brazilian Investment (2007-2018)

Recently, the Panama and Pandora papers have shown the extent of these activities. These papers cover the activities of different actors in countries across the world. In the case of low-income countries, there is clear participation of many politicians and companies which colluded with financial institutions in high-income countries to hide their wealth.

7.4 Foreign Aid

Foreign aid is the voluntary transfer of funds to support development, humanitarian and peace efforts in places experiencing periods of crisis. In general, we can recognize two main categories of aid:

Humanitarian assistance: this type of aid is targeted to areas that experience conflict, natural disasters, and displacement. This type of aid is provided based on need. It is supposed to be impartial, universal, and based on human dignity principles.

Development programs: this type of aid promotes programs that target development in different areas, such as health, education, economic development, infrastructure, governance, and in some instances, peace and security. The way this type of program is targeted is a little bit different. It depends on the different priorities that we will examine in the course.

In a seminal article, Alesina and Dollar (1998) show that strategic considerations of the donor dictate foreign aid, and not necessarily by the economic needs of the recipient country. According to the authors, colonial legacies and political alliances are the most important factors explaining foreign aid flows. The recipient country’s income is only relevant up to a level, and usually for the case of donors that do not have political or colonial linkages with those countries. This is mostly the case of Nordic countries.

This goes in line with Cheeseman and Fisher’s (2019) argument on why many ‘Big Men’ in Africa were able to stay in power between independence and the end of the Cold War, irrespective of their domestic scores on human rights and democratization. Both the East and the West used African and Latin American countries as proxies in the Cold War and tried to gain allies. African ‘Big Men’ used this in their favor, as they could go with the highest provider of aid, and change according to their needs. It is only at the end of the Cold War period that Western countries started to pay more attention to governance issues. In recent decades, there has been a shift in the strategies followed by international donors. They are now mostly focused on specific micro-projects, instead of substantial infrastructure projects.

As China has become a central geopolitical figure, it has become one of the most crucial aid donors. However, contrary to the role Western countries play in promoting democratic values, China is not focused on the national politics of the recipient countries. Instead, Chinese aid mostly depends on the country’s national interest and the priorities of recipient countries, leading to an ‘openly mutually beneficial relation’ (Kjøllesdal and Welle-Strand, 2010).

China has become a key donor for African countries, particularly since the country has centered on the funding of mega-projects in the region15. However, one of the main critiques about Chinese intervention in Africa is that, contrary to the case of Western foreign aid figures, that are published by the OECD’s Official Development Assistance (ODA), Chinese aid is less transparent and it is not very clear if funds received by African governments refer to grants or concessional loans, and if it comes from private or public sources Bräutigam, 2011.

Does foreign aid promote development?

This is a very complicated question, with multiple dimensions and with no single answer. Some scholars, such as Sachs (2014), argue that foreign aid is a crucial tool to reduce poverty and promote development. This view has been empirically supported by Galiani et al.(2016), who find that aid promotes economic growth.

Other scholars, however, argue that foreign aid is detrimental to the development of low-income countries. Easterly (2012), for instance, argues that aid does not promote growth and that believing the contrary is to simplify the multiple realities of these countries. This position is shared by authors such as Moyo (2010) that argues that African countries that have traditionally relied more on aid are trapped in aid dependency and poverty cycles.

More recently, a vision on data-driven programs has been proposed by Banerjee and Duflo (2011). The scholars, who won the Nobel prize in 2018 for their data-driven perspective that has largely impacted development economics, argue that the use of randomized control trials (RCTs) can help to tailor effective aid programs to reduce poverty and promote development16.

In recent years, a more nuanced vision has emerged. For instance, Dionne (2018) argues that foreign donors are usually disconnected from the local realities and asks us “[to] listen to the opinions and priorities of the ordinary people to whom interventions are targeted”. Edwards (2014) argues that the effects of aid are non-linear and need to be examined in a historical perspective, as simple cross-country analysis do not capture the complexity of these effects.

Part of the critiques to aid is linked to funding leakage by the local elites. In a recent (and controversial) paper, Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers (2020) show that disbursements of foreign aid coincide with increases in bank deposits in offshore financial centers. The calculated implied leakage is approximately 7.5%.

7.5 Seminar Questions Module 4

7.5.0.1 Week 10:

Structuring the Economy

- Is it possible for structural transformation to promote prosperity? Does this need to be promoted by the industrial sector or is possible to envision a different strategy?

7.5.0.2 Week 11:

International Trade and Investment

Why do we see different conclusions about the effect of trade liberalization on economic development?

What is the role of the financial sector in promoting development? What are some of the risks linked to it?

7.5.0.3 Week 12:

Foreign Aid

- Do an assessment on the role of foreign aid on development based on the readings and our discussion in class.

7.6 Activities Module 4

- We will do some case study analysis to see how structural transformation has promoted or hindered economic growth.

- Trade liberalization has been one of the main policies proposed to promote economic development. We will debate about its pros and cons. Esther Duflo’s Ted Talk: Social Experiments to fight poverty

- Video: Dambisa Moyo on her vision for Africa & what’s wrong with aid

- We will have a debate on the effects of Foreign Aid.

- A research project: Who gives aid to whom? We will find the links

7.7 Readings Module 4

7.7.1 Required Readings Module 4

7.7.1.1 Week 10:

Structuring the Economy

- Easterly, W. (2002). Solow’s Surprise: Investment is not the Key to Growth. In The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Byerlee, D., de Janvry, A. Sadouet, E. (2009). Agriculture for Development: Toward a New Paradigm. Annual Review of Resource Economics Vol. 1. pp. 15-31.

- Newman et al. (2016). Industrialization Efforts and Outcomes. In Newman et al (eds.) “Made in Africa: Learning to Compete in Industry. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution

- Cunningham, S. (2011). “Understanding market failures in an economic development context. Creative Commons.

7.7.1.2 Week 11:

Trade and Development

- Oatley, Th. (2019). “International Political Economy”, 6th. Ed. New York: Routledge. Chapter 6

Investment and financial development

- Alfaro, L. and Chauvin, J. (2017). Foreign Direct Investment, Finance, and Economic Development. In Encyclopedia of International Economics and Global Trade.

- Video: Suri, (2018) “Paving a path to financial well-being”

7.7.1.3 Week 12:

Foreign aid

- Edwards, S. (2014). “Economic Development and the Effectiveness of Foreign Aid: A Historical Perspective” NBER Working paper 20685.

- Easterly, W. (2008). “Can The West Save Africa”. NBER Working Papers Working Paper 14363.

- Easterly, W. and Pfutze, T. (2008). “Where Does the Money Go? Best and Worst Practices in Foreign Aid”. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 22(2). Pp. 29-52

7.7.2 Additional Readings and Resources Module 4

Economic Structure and Development

Agriculture

- Benin, S., Wood, S. and Nin-Pratt, A. (2016). Agricultural productivity in Africa: Trends, patterns, and determinants. Washington, D.C.: IFPRI- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Casaburi, L. Protecting Insecure Farmers

- Njagi, K. “Land rights battle inches Kenyan rice farmers closer to title deeds”. Ngurubani, Kenya: Reuters. July 21, 2020

- Movies to watch: “The boy who harnessed the wind”

Industrial Policy

- Newman et al. (2016). Why Industry Matters for Africa. In Newman et al (eds.) “Made in Africa: Learning to Compete in Industry. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution

- Oqubay, A. (2015). Climbing without Ladders. In Oqubay “Made in Africa: Industrial Policy in Ethiopia” Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online

Trade and Development

- Oatley, Th. (2019). “International Political Economy”, 6th. Ed. New York: Routledge. Chapter 7

- Atkin, and Kandelwal (2019). How distortions alter the impacts of international trade in developing countries. NBER Working Paper 26230. Washington, D.C.

- Dragusanu, and Nunn, N. (2018) The Effects of Fair Trade Certification: Evidence from Coffee Producers in Costa Rica. Working Paper.

- Irwin, D. (2019). Does Trade Reform Promote Economic Growth? A Review of Recent Evidence. Washington, D.C.:Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- Pavnick, N. (2019). The Impact of Trade on Inequality in Developing Countries.Working Paper

Foreign Aid

- U.S. Foreign Assistance

- Morris et al. (2020). “Chinese and World Bank Lending Terms: A Systematic Comparison Across 157 Countries and 15 Years”. CGD Policy Paper 170

The private sector

- Besley and Persson (2014). Why Do Developing Countries Tax So Little?. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol 28(4). pp: 99-120

- Oatley, Th. (2019). “International Political Economy”, 6th. Ed. New York: Routledge. Chapter 14