5 Reasoning on DAGs

5.1 Recap: Causal models as generative models

Our goal is to understand causal modeling within the context of generative machine learning. We just examined one generative machine learning framework called Bayesian networks (BNs) and how we can use BNs as causal models.

5.1.1 Ladder of causality (slides)

- Associative:

- Broad class of statistically learned models (discriminiative and generative)

- Includes deep learning (unless you tweak it)

- Intervention

- Why associative models can’t do this – changing the joint

- Causal Bayes nets

- Tradition PPL program

- Counterfactual

- Causal Bayesian networks can’t do this

- Structural causal models – can be implemented in a PPL

5.1.2 Some definitions and notation

- Joint probability distribution: \(P_{\mathbb{X}}\)

- Density \(P_{\mathbb{X}=x} = \pi(x_1, ..., x_d)\)

- Bivariate \(P_{Z, Y}\), marginal \(P_{Z}\), conditional \(P_{Z|Y}\)

- Generative model \(\mathbb{M}\) is a machine learning model that “entails” joint distribution, either explicitly or implicitly

- We denote the joint probability distribution “entailed” by a generative model as \(P_{\mathbb{X}}^{\mathbb{M}}\)

- Directed acyclic graph DAG \(\mathbb(G) = (V, E)\), where E is a set of directed edges.

- Parents in the DAG: Parents of \(X_j\) in the DAG \(\mathbb(G)\) is denoted \(\text{pa}_j^{\mathbb{G}}\)

- A Bayesian network is a generative model that entails a joint distribution that factorizes over a DAG.

- A causal generative model is a generative model of a causal mechanism.

- A causal Bayesian networks is a causal generative model that is simply a Bayesian network where the direction of edges in the DAG represent causality.

- Probabilistic programming: Writing generative models as program. Usually done with a framework that provides a DSL and abstractions for inference

- “Causal program”: Let’s call this a probabilistic program that As with a causal Bayesian network, you can write your program in a way that orders the steps of its execution according to cause and effect.

5.1.3 Difference between Bayesian networks and probabilistic programming

- BNs have more constraint

- Probabilistic relationships limited to conditional probability distributions (CPDs) factored according to a DAG.

- Frameworks typically limit you to a small set of parametric CPDs (e.g., Gaussian, multinomial).

- bnlearn allows multinomial or ordinal variables for discrete, Gaussian for continuous.

- PPLs let you represent relations any way you like so long as you can represent them in code.

- Nonparameterics

- Strange distributions

- Control flow and recursion

- DAGs all variables are known in advance

- “Open world models”: control flow may create new variables (blackboard)

X = Bernoulli(p) if X == 1: Y = Gaussian(0, 1)X = Poisson(λ) Y = zeros(X) Y[0] = [Gaussian(0, 1)] for i in range(1, X): Y[i] = Gaussian(Y[i-1], 1))

- Inference

- Inference is easier in BNs given the constraints

- PGM inference such as belief probagation, variable elimination

- In PPLs inference is tougher

- Require you to become something of an inference expert

- That said, PPL developers provide inference abstractions so you don’t have to work from scratch

- PPLs use cutting-edge inference algorithms

- Include tensor-based frameworks like Tensorflow and PyTorch, allow you to build on data science intuition.

- Stochastic variation inference

- Minibatching – process groups of training examples simultaneously to take advantage of modern hardware like GPUs

- Finally, it is easier to reason about the joint distribution if you have a DAG.

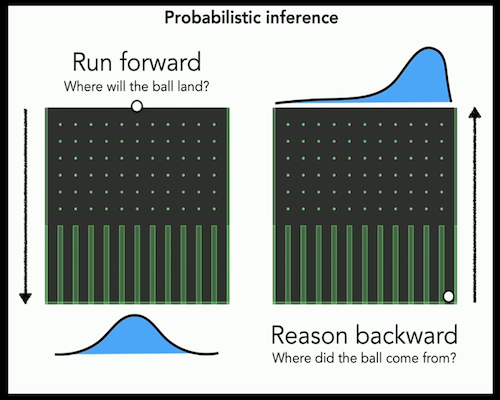

5.2 Reasoning with DAGs

5.2.1 Intuition

- DAGs as a graphical language for reasoning about conditional independence

- Impossible to learn a language all at once, we’ll focus on learning what it can do for us

5.2.2 Reading DAGs as factorizations

5.2.2.1 Recap on core concepts

- Conditional probability

- Conditional independence

- Notation: \(U \perp_{P_{\mathbb{X}}} W|V\)

- Implications to factorization

- Conditional independence in the joint changes the DAG

5.2.3 Core graphical concepts

- A path in \(\mathbb{G}\) is a sequence of edges between two vertices

- todo: formal notation, see page 82 of Peters 2017

- Pearl’s d-seperation – Reading conditional independence from the DAG

- todo: formal notation

- So what? We saw how conditional independence shapes the DAG. This shows

- V-structures / Colliders

- moral v-structure

- immoral v-structure and conditional independence

- Sprinkler example

5.2.4 Taking a step back – what does conditional independence have to do with causality?

- correlation vs causation

- Latent variables and confounding

- That v-structure example was causal

- If you can’t remember, use the algorithm (bnlearn, pgmpy)

- Reduces the problem to reasoning about the joint probability distribution to graph algorithms.

- Without a DAG, no d-separation. Could there be a more general form of d-separation that could operate on a probabilistic program?

5.2.5 Markov Property

- Markov blanket

- probability definition

- DAG definition (slides)

- Implications to prediction

- Markov property (slides)

- Global

- Local

- Markov factorization

- Markov equivalence

- Recap: The definition conditional probability is P(A|B) = P(A,B)/P(B) (blackboard)

- This definition means you can factorize any joint into a product of conditionals. For example P(A, B, C) = P(A)P(B|A)P(C|A, B)

- A product of conditionals can be represented as a DAG. In this case with edges {A-> B, B -> C, A->C}.

- But you can also factorize P(A, B, C) in to P(C)P(B|C)P(A|B,C), getting edges {C->B, B->A, C->A}.

- So you have two different DAGs that are equivalent factorizations of the joint probability. Call this equivalence Markov equivalence.

- Generally, given a DAG, the set that includes that DAG and all the DAGs that are Markov equivalent to that DAG are called a Markov equivalence class.

- PDAG is a compact representation of the equivalence class

- When you have an equivalence class of some thing, trying to find some meaningful representation of that class without enumerating all of its members is a hard thing to do.

- Usually the best you can do is look for some kind of isomorphism between two objects to test if they are equivalent, according to some definition of equivalence

- The nice thing about the equivalence classes of DAGs is that all the DAGs will have the same “skeleton”, meaning set of connections between nodes.

- The difference is that some or all of those edges will have different directions in different DAGs.

- This is where we get the PDAG as a compact representation of an equivalence class. The PDAG has the same skeleton as all of the members of the equivalence class.

- The undirected edges in the PDAG correspond to edges that vary in direction among members of the class.

- A directed edge in the PDAG mean that all members of the class have that edge oriented in that direction.

- There are other graphical representations of joint probability distributions

- Undirected graph – doesn’t admit causal reasoning

- Ancestral graphs (slide) – Doesnt directly map to a generative model

5.3 Causality and DAGs

- Assume no latent variables (very strong assumption)

- Causation vs correlation – only two options

- A second look at PDAGs