Chapter 5 Origins and Sources

5.0.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter we examined the issues involved in developing statistics on patent trends for marine genetic resources from the deep-sea. One of the key challenges that emerged from quantitative approaches is the difficulty of establishing whether genetic material was sourced from Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction or from inside the EEZ or terrestrial environments. In this chapter we present a brief summary of the results of efforts to identify the origins and sources of genetic material in patent data with detailed information provided in Annex 2.

International debates on access and benefit-sharing typically focus on the nature of the rights granted by patent protection. In practice, a fundamental purpose of the patent system is the disclosure of new and useful inventions that become freely available to the public following the expiry of the term of protection (typically 20 years). To enable the realisation of this purpose, the patent system includes rules on the type of information that must be provided in a patent document. Patent offices have also heavily invested in information technology to make patent data publicly available in electronic form. The most notable example of this is the European Patent Office esp@cenet worldwide database that provides access to over 60 million patent documents. Other important examples include the free availability of millions of patent records from the United States Patent and Trademark Office used in the present research.

Increasing interest in the governance of genetic resources and access and benefit-sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity and at WIPO has focused on requirements for disclosure of the precise origin or source of genetic resources, or associated traditional knowledge in patent applications [92,93]. These debates are informed by demand for greater recognition of the sovereign rights of states over natural resources and for benefit-sharing with states, and communities, from which genetic resources originate. Discussions on disclosure of origin are ongoing at the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (the IGC) at WIPO with a view to the potential adoption of a new instrument or instruments.

In contrast with debates grounded in the sovereign rights of states, or respecting the human rights of indigenous peoples and local communities, in debates on marine genetic resources from the deep-sea we are confronted by a situation where there are no individual sovereigns. This raises the question of the possibility of benefit-sharing arising from the commercial exploitation of marine genetic resources and is linked in existing debates on marine genetic resources from ABNJ with various proposals for some form of benefit-sharing mechanism [15,18,19,94].

In this chapter we set these important questions to one side and instead focus on clarifying the nature of existing information on the origins or sources of genetic material from Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction in patent documents.

In approaching the data presented below and in Annex 2 we would emphasise that applicants for patent rights are not required to provide precise information on the origin or source of genetic material except where this is required to meet the criteria of sufficiency of disclosure for the reproduction of the invention as a condition of patentability22. Given that applicants are not required to provide precise information on the origin or sources of material outside of these conditions, we must recognise that our analysis is confined to situations where applicants choose to provide information on origins or sources. However, as we will see, we can also learn a great deal about origins and sources by investigating existing information in patent documents.

In this chapter we begin with a description of the methodology for investigating origins and sources. We then present a comparison of the results of mapping named places in the scientific literature and the patent literature. Finally we discuss the main types of disclosure of origin and sources in patent documents and provide a series of reference examples in Annex 2. This data confirms many of the observations made in the existing literature about origins and sources but serves as a useful reference set of actual examples. We conclude by arguing that, within the limitations noted above, on the balance of the available evidence the majority of genetic material appearing in patent documents is derived from locations inside the EEZ including deep-water sites. However, we also argue that greater knowledge and understanding of the role of marine genetic resources from ABNJ in innovation could be achieved by encouraging applicants to provide more precise information on the origins or sources of material [95]. When coupled with the statistical and network analysis presented in chapter 4 this could provide important insights into international cooperation, benefit-sharing, technology and knowledge transfer in patent activity. However, to be successful, encouraging applicants to provide more information will also require a very carefully considered approach to issues around patents and benefit-sharing.

5.0.2 Methodology

The identification of the potential origins or sources of genetic material in patent data requires the investigation of the names of habitats and places in the text of patent documents that are known to contain a marine species name. It is important to emphasise that the research was confined to patent publications from the European Patent Office, the United States Patent and Trademark Office and the Patent Cooperation Treaty published between 1976 and October 2013.

In total we identified 61,045 patent publications that contained a reference to a marine species of which 8,039 publications contained references to species known to occur in the deep-sea. As this suggests the challenge of identifying places and habitats in patent documents is not trivial and is inevitably limited by the availability of both resources and time. To approach searching the documents for information on origins or sources we used a strategy with five components:

We used 484,599 words and phrases from the scientific literature (Chapter 3) and identified 93,454 phrases that also appeared in patent documents. These results were manually reviewed in VantagePoint software to build a thesaurus of 9,651 place, habitat, depth, time and genomics related terms for tagging in patent documents;

The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) dataset consisting of 3,762 undersea feature names was used to search the patent data;

The InterRidge Vents database of known hydrothermal vents was used to search the patent data;

Specialist searches were conducted for 16S ribosomal DNA and related genomics references in patent data to investigate metagenomic information;

Additional specialist searches were conducted to cross-test data capture on issues such as hydrothermal vents, references to new species and new strains.

To control for the size of the document sets they were divided by depth and topic. In one case (hydrothermal vents) a specialist dataset was created to check for data capture. In order to minimise repetition of the same document, the tagging was performed by patent family (first filings). Details of the coded documents are provided in Figure 5.1. The computational tagging approach included a requirement that the document contained a marine species name and either a place or habitat name from the thesaurus as a condition for inclusion. This process excluded documents that contained a marine species name but did not contain a selected place or habitat name.

Figure 5.1: Tagged First Filings

| Dataset | First Filing Counts |

|---|---|

|

11,629 |

|

2,512 |

|

118 |

|

2,530 |

|

1,455 |

As this makes clear a very large number of documents were available that contained a species name in conjunction with a habitat or place name. However, habitat or place names frequently appear in documents for other reasons. In view of time constraints, we limited the review to those paragraphs where a marine species occurred (intersected) with either a place or habitat name in the same paragraph.

Given the size of the raw results set for the epipelagic zone and time constraints, attention focused on species listed outside the epipelagic zone. The whole patent texts for the selected documents were obtained from the Thomson Innovation database and patent publication numbers provided in this chapter are taken from Thomson Innovation23. The review was conducted using MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software. MAXQDA allows the whole text of patents to be loaded for manual review and manual tagging. The review was conducted using a weighting score 0 = exclude, 1= keep, 2 = review and 4 = interesting for other reasons. The results were reviewed and resolved by a second team member for the purpose of ensuring accuracy, particularly in complex cases.

In the final step of this stage of the research we mapped the references to places in the patent data using the GEBCO Gazetteer and InterRidge Vents Database. Map imagery is reproduced from the GEBCO_08 Grid, version 20100927, www.gebco.net. This permits comparison between research activities identified in Chapter 3 with places referenced in the patent data. Because GEBCO data is provided as polygons and lines for larger geographical features, such as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge or the East Pacific Rise, the centre point of the polygon was used to generate marks on the map. For large features this will cluster results around a central point in the polygon rather than reflect actual points of collection (e.g. from widely dispersed hydrothermal vents or cold seeps across the feature). More importantly, the results using the GEBCO Gazetteer and InterRidge Vents database are confined to terms appearing in those datasets. The mapping exercise will not capture more general references to places (i.e. Antarctica, the Southern Ocean etc.) that appear in the main thesaurus. Approaches to mapping more general references could be improved in any future research.

5.0.3 Mapping Places in the Scientific Literature and Patent Data

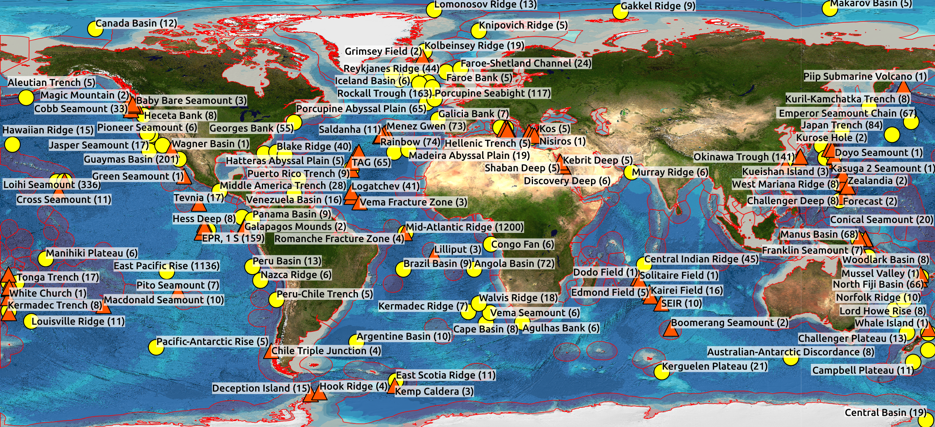

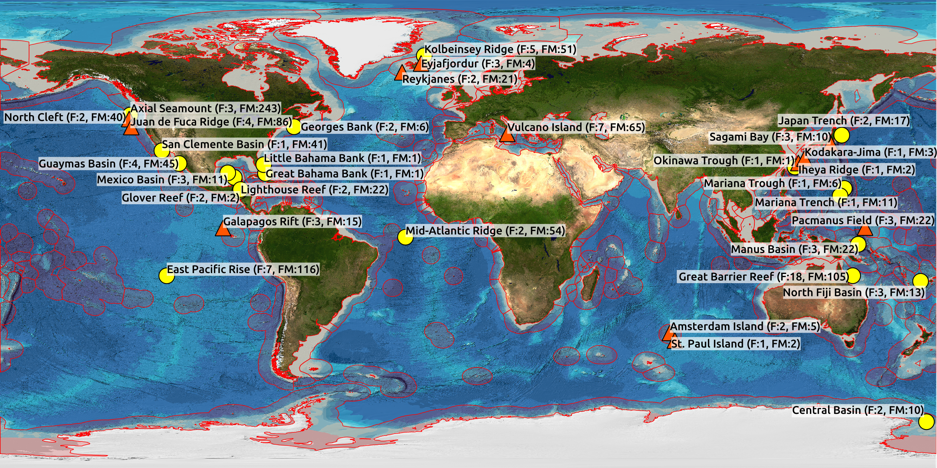

In Chapter 3 we presented a map of the main research locations referenced in the titles, abstracts and keywords of a dataset of 24,259 marine scientific publications. This map is reproduced in Figure 5.2 below with the EEZ marked in red. Numbers associated with place names refer to the number of publications in the scientific literature. Figure 5.3 presents the details of named places in the patent data. Named places from the GEBCO Gazetteer appear in circles with triangles representing hydrothermal vents listed in the InterRidge Vents database. In approaching Figure 5.3 note that F refers to patent families (first filings) and FM refers to global family members.

In considering the map of the patent data we would emphasise that there is room for improvement in terms of data capture across the marine data, notably in the dataset for the epipelagic zone (0-200 m). Furthermore, our analysis is confined to first filings with the United States Patent and Trademark Office, the European Patent Office and the World Intellectual Property Organization. Nevertheless, by approaching the data from multiple directions (e.g. WIPO documents containing sequence data, and patents referencing 16S data) we believe the data to be robust.

The most striking feature in comparing Figure 5.2 and Figure 5.3 is that named places in the patent literature are dominated by deep-sea sites inside the EEZ. Furthermore, and with the notable exception of the inclusion of the Great Barrier Reef, the number of patent filings that make reference to each place is typically under 5 filings. However, patent family sizes arising from the small number of filings can be significant.

Figure 5.2: Named places in the Scientific Literature

Figure 5.3: Named Places in the Patent Literature

While recognising the limitations of this approach noted above, the main outcome of the research to date is that marine genetic resources associated with deep-sea organisms are predominantly drawn from within national jurisdictions. This is logical when we consider the logistical difficulties and financial costs involved in research in the deep-sea. Furthermore, as both Figure 5.2 and 5.3 make clear there are major deep-water sites within the boundaries of the EEZ. As such it is unclear precisely why Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ) would be a priority for bioprospecting except as an offshoot from publicly funded research expeditions. Mapping helps to bring these issues into focus.

In Annex 2 we provide a set of examples from our research that illustrate the issues involved in patents making reference to places and habitats. The purpose of this exercise is to inform the policy debate around the range of issues involved in identifying the sources of patent data from the deep-sea. We would note that not all of these examples are from ABNJ but are instead intended to provide a representative overview for marine genetic resources. The reference examples in Annex 2 have been selected to illustrate the degree of clarity found in references to origins or sources by taking the paragraph or paragraphs which best describe the source of genetic material. In reviewing these examples we identified a number of clear themes:

Samples isolated from named locations. In these cases it is usually stated that a strain had been isolated from, or discovered at, a location such as the East Manus Basin or the Kolbeinsey Ridge, or that a specimen had been cultured from a species taken from a named location such as the Juan de Fuca Ridge. However, in these cases it is not clear whether the inventors themselves collected the samples or they had acquired the samples via a third party such as a commercial source.

Samples from broad geographical areas. Sometimes a species with wide distribution, such as krill or a fish, is described as having been obtained from a general location. This was usually the name of an ocean or sea such as the Mediterranean Sea or ‘seas around Japan’.

Specific collection locations. We identified one clear case where coordinates were given for the location of a collection (Aplidium cyaneum taken from the Weddell Sea). In other cases coordinates were provided but obscured by machine code from the translation of documents from .pdf format. In other cases more precise location names were used such as Georges Bank for the harvesting of fish and coastal areas within EEZs such as Arcachon Bay in France, the Gulf coast of Florida or Chesterfield Island in the Pacific. Also included in this category are cases where specimens have been collected after being stranded on beaches in Hawaii and Australia.

Acquired through a third party. Microorganisms in particular are often obtained via a culture collection or through commercial suppliers. In some cases this will be for a branded product such as DeepVent.

Unspecified location habitat descriptions. It is sometimes the case that a species is described as being from a habitat type such as a hydrothermal vent, a given water depth or from a high temperature environment. In these cases no further indication of the origin is given.

This analysis reveals that it is extremely difficult to ascertain the precise source of genetic material from Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction as used by patent applicants. The wording of a patent can often be read in a number of ways, in particular where a specimen is described as having been isolated from a given location. Thus, while an applicant may state that a specimen was isolated from a given location it does not necessarily follow that the applicant actually collected and isolated the sample. As these particular examples often involve species from extreme environments it is very probable that these specimens have been obtained through a third party, simply because of the difficulty of obtaining a specimen from its original source. Additionally it is widely recognised that pharmaceutical research typically relies on biobank and database samples rather than direct collection of specimens [96]. It is noteworthy that in cases where species were collected from beaches or near-shore locations more information is provided regarding the source location and whether it is the applicant (or an agent of the applicant) who harvested the specimens. This might indicate that where actual effort is required to obtain specimens it is mentioned in the patent document. However, in other cases, such as the Juan de Fuca Ridge, applicants appear to mention the original source of the material as a general point of interest even where it is a widely available from commercial sources.

5.0.4 New Species and Strains in the Patent Data

The present research has focused on the analysis of binomial species names in patent data. Given that new distinct strains of a specific species may be the focus of an invention we conducted additional exploratory research for references to new strains and new species. Figure 5.4 presents a summary of these results. The term WIPO refers to WIPO sequence data, 16S refers to patent documents containing references to 16S rDNA and related terms while Minus 200 m refers to the sectioning of documents into a dataset containing marine species known to occur below 200 metres in depth.

In considering this summary of results it is clear that the references to new strains or new species in the marine patent data predominantly refer to strains or species originating inside the EEZ. We would emphasise that a more comprehensive review of these references is merited in any future research.

Figure 5.4: References to New Species or Strains in Patent Data

| Genus or Species | Inside EEZ | Outside EEZ | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanobacillus iheyensis WO2012116230A (WIPO) WO2013042900A (16s) Methodology | II | ||

| Psychrobacter pacificensis EP1193312A (16s) | I | ||

| Protolyngbya sp. EP2465515A (16s) - Not deep sea | I | ||

| Pseudomonas strain ChG 3-3 WO19970433A (16s) | I | ||

| Thermococcus gorgonarius (new strain) WO1998014590A (Minus 200 m) | I | ||

| Vibrio harveyi strain MM32 WO2003064592A (WIPO) WO2004101826A (WIPO) | II | ||

| Clostridium ganghwense strain WO2011011683A (WIPO) | I | ||

| Dunaliella salina HT04 strain WO2010054325A (WIPO) (16s) | I | ||

| Aureobasidium pullulans strain NP1221 WO2009154320A1 (WIPO) | I | ||

| Aureobasidium pullulans strain ADK-34 EP1522282A (16s) | I | ||

| Microsporidium sp. US20040047840A (Minus 200 m) (16s) | I | ||

| Olleya marilimosa VIG2317 strain EP2441433A (16s), US20120095108A (16s) | II | ||

| Aerococcus viridial P3-1 & P3-2 - or possibly new species WO2005109960A | I |

5.0.5 Conclusions

This chapter has presented a brief summary of the results of research on the origins or sources of marine genetic resources in patent data from the European Patent Office, the United States Patent and Trademark Office and the Patent Cooperation Treaty. A set of reference examples from the research are provided in Annex 2. The main findings of this research can be summarised as follows.

On balance, references to origins or sources inside the EEZ dominate existing references within patent documents for marine genetic material. This includes deep-water locations inside the EEZ and reflects patterns in marine genetic research identified elsewhere in this research. This concentration is logical when we consider the financial costs and logistical challenges of research in deep water locations. Exceptions to this pattern include the East Pacific Rise and the Mid-Atlantic ridge.

References to places in patent documents display a pattern consisting of: a) samples originally isolated from named locations; b) samples taken from broad geographical areas (e.g. seas around Japan); c) specific collection locations, including rare instances of georeferenced coordinates; d) material acquired through a third party, notably a commercial source, a collection or a DNA sequence or protein database; e) habitats in unspecified locations such as hydrothermal vents.

Analysis reveals that it cannot be assumed that a reference to a sample originating from a particular location signifies that applicants actually collected the sample. The data suggests that more often than not the applicants obtained the material through an intermediary and that information on the origin or material is provided as a point of interest. An exception to this general observation are those instances where disclosure of the organism, or its genome data, is required to meet the sufficiency of disclosure requirement under patent law. This is typically met through reference to a deposit under the Budapest Treaty or reference to the relevant sequence data.

It would be a mistake to conclude that applicants are seeking to disguise the source of material to protect their commercial interest. In particular, we are struck that applicants are willing to provide information on the ultimate origin of genetic material (e.g. an industrial enzyme) even where this information is neither relevant nor required. That is, in the case of deep-sea material, applicants appear to be willing to offer information as a point of interest.

The willingness of applicants to offer additional information on the origins of deep-sea material suggests that a request to provide additional information, where known, on the geographic origin of genetic material could meet with a positive response. This would have the advantage of enhancing knowledge of the role of genetic resources from Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction in innovation as a contribution to understanding and recognising the value of genetic resources from the deep-sea. In contrast with debates at WIPO linked to disclosure of origin for genetic resources inside national jurisdictions, we assume that the provision of additional information would be voluntary and would not carry consequences for obtaining or maintaining patent rights. We recognise that substantive concerns exist on whether genetic resources from ABNJ should be the subject of patent rights. However, in our view the evidence for patent activity originating from marine genetic resources in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction is presently limited. Much could be achieved in clarifying and valuing the role of marine genetic resources from ABNJ in innovation by encouraging voluntary action by patent applicants.

In recommending the increased provision of information by patent applicants we recognise that there will be a need to consider the relationship between enhanced provision of information on genetic material from Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction and debates on mandatory disclosure of origin for genetic resources and traditional knowledge from within national jurisdictions presently under discussion at WIPO.

In the case of microorganisms this requirement is typically met through the deposit of a sample with a type culture collection serving as an International Depositary Authority under 1980 Budapest Treaty on the International Recognition of the Deposit of Microorganisms for the Purposes of Patent Procedure. In addition, on a voluntary basis, Article 27 of the European Biotechnology Directive (98/44/EC) specifies: “Whereas if an invention is based on biological material of plant or animal origin or if it uses such material, the patent application should, where appropriate, include information on the geographical origin of such material, if known; whereas this is without prejudice to the processing of patent applications or the validity of rights arising from granted patents.”↩

Documents with these publication numbers can readily be retrieved from the esp@cenet database using Advanced search. However, in a small number of cases number formats may vary for the same document across databases. Typically this involves additional zeros used as padding or a truncated year e.g. 86 for 1986.↩