Chapter 3 Deep-Sea Marine Scientific Literature

3.0.1 Introduction

This chapter provides empirical data on trends in deep-sea marine research and then focuses on the position of the UK in this data using scientometrics approaches.

Research on the scientific literature was carried out by conducting searches of Thomson Reuters Web of Science. We initiated research with a general scoping search on the deep-sea that produced 6,287 publications. The scoping search was reviewed using VantagePoint analytics and natural language processing software from Search Technology Inc. to identify key words and phrases for specialist topics such as methane seeps and mud volcanoes. To gain an overview of general trends in relation to marine literature we ran a search for terms such as marine, deep-sea, ocean and oceans11. In a series of iterative steps we progressively refined the search terms to target the deep-sea, hydrothermal vents, the seafloor and seabed and marine natural products to produce a working dataset with 24,259 distinct publications12. The aim of this exercise was not to produce a definitive dataset for deep-sea research and subjects such as marine natural products but to capture a large representative sample of data in a structured way (Annex 1).

3.0.2 Research Trends

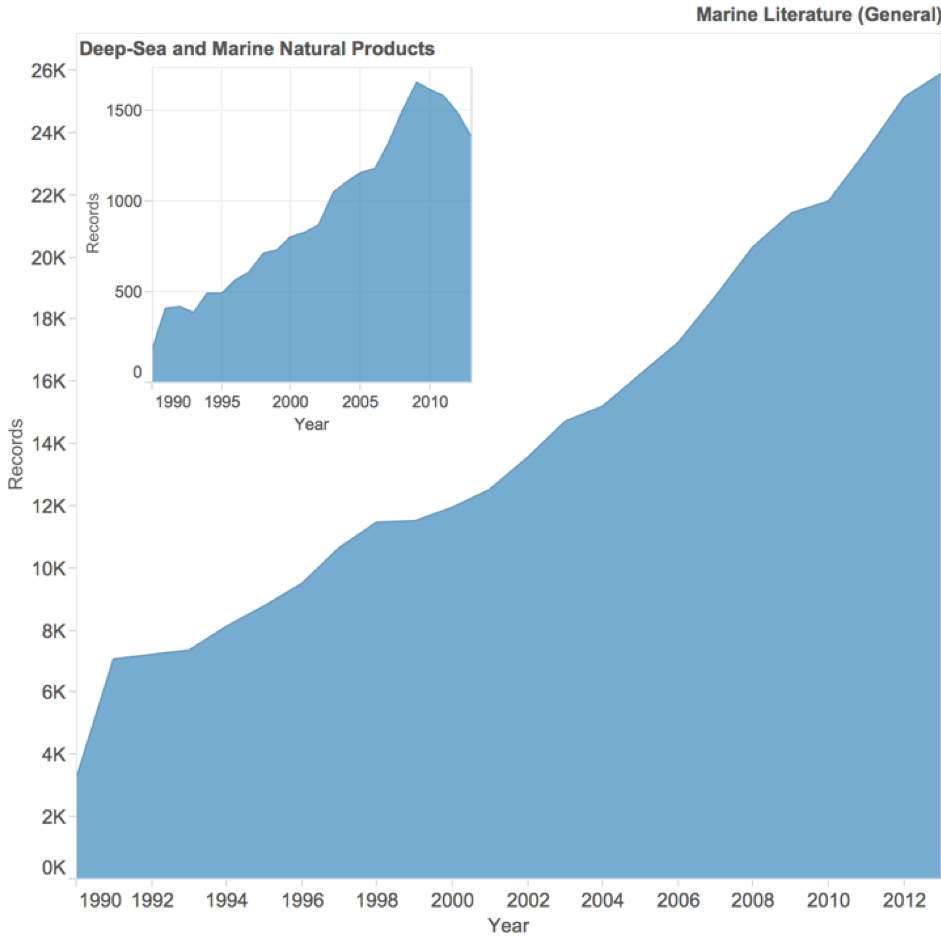

Figure 3.1 displays overall trends in the scientific literature making reference to the terms marine, deep-sea, oceans or the seabed between 1990 and the end of 2013. It is important to note that this will capture a wide range of scientific and technology areas connected with marine issues. However, this data demonstrates an increasing trend in references to marine subjects across all areas of scientific research and provides a simple ball-park indicator for literature focusing on marine and deep-sea issues. Inset in Figure 3.1 is our calculation of trends in research publications based on key terms and phrases in our 24,259 publication dataset relating to the deep-sea and specialised habitats in Web of Science data including marine natural products research13. It can readily be seen that there has been a growing scientific interest in deep-sea related research with 799 publications recorded in 2000 and a peak of 1,654 publications in 2009 and 1,163 in 2010, around the time of the Census of Marine Life, before a declining trend from this peak to 1,480 in 2012 and a provisional 1,350 in 2013.

Figure 3.1: Trends in Marine Scientific Literature

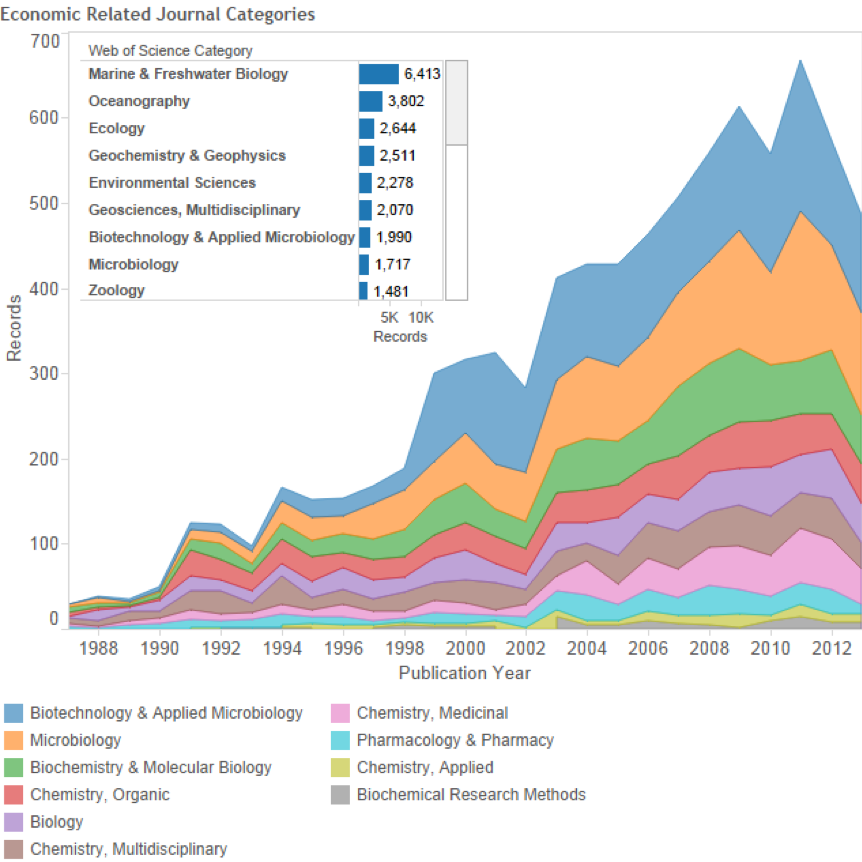

This data can be further broken down into the Subject Categories used by Web of Science to categorise journals. Figure 3.2 shows the top journal subject categories across the dataset of 24,259 publications (inset) and trends in publications in journal categories linked to marine genetic resources and economic value.

Figure 3.2: Trends by Journal Subject Category

This data appears to support the argument that there is an increasing interest in deep-sea marine related genetic resources within journals addressing biotechnology and applied microbiology along with microbiology and biochemistry and molecular biology. However, it is important to note that we are not in a position to directly confirm this through the analysis of deep-sea species appearing in the data.

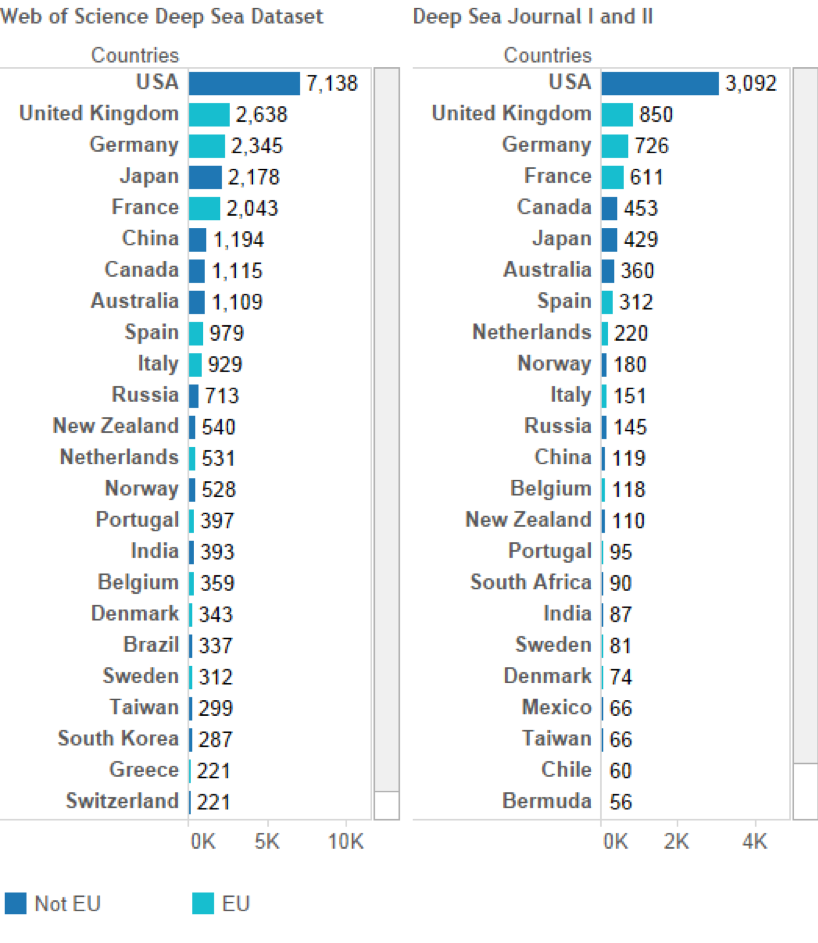

Figure 3.3 displays the top countries with authors involved in publications including members of the European Union across the Web of Science dataset. To confirm these findings we also display the country rankings for a second dataset of 7,459 publications in two main deep-sea research journals known as Deep-Sea Research Part I–Oceanographic Research Papers and Deep-Sea Research Part II–Topical Studies in Oceanography published between 1979 and early 2014.

Figure 3.3 Top Countries in Deep-Sea and Marine Natural Products Research (Publication Counts)

Figure 3.3 demonstrates that the UK ranks second in our publication data after the United States and is the top ranking country for scientific publications in the European Union across both datasets. The importance of research published by researchers from EU member states is apparent in both cases with Japan, Canada, China, Australia and the Russian Federation also prominent in the data. The presence of India and Brazil is notable in the main dataset with South Africa also emerging in the top 25 in the Deep-Sea Research journals.

3.0.3 Research Collaboration and Funding

In practice, researchers increasingly work in networks characterised by collaboration between researchers from multiple countries. This reflects the international nature of modern scientific research and trends towards training and knowledge exchange between countries. The existence of such networks is likely to be particularly important in deep-sea research in ABNJ due to limitations in access to technologies such as ships, submersibles, remote and autonomously operated vehicles, sea-floor observatories and specialised laboratory equipment.

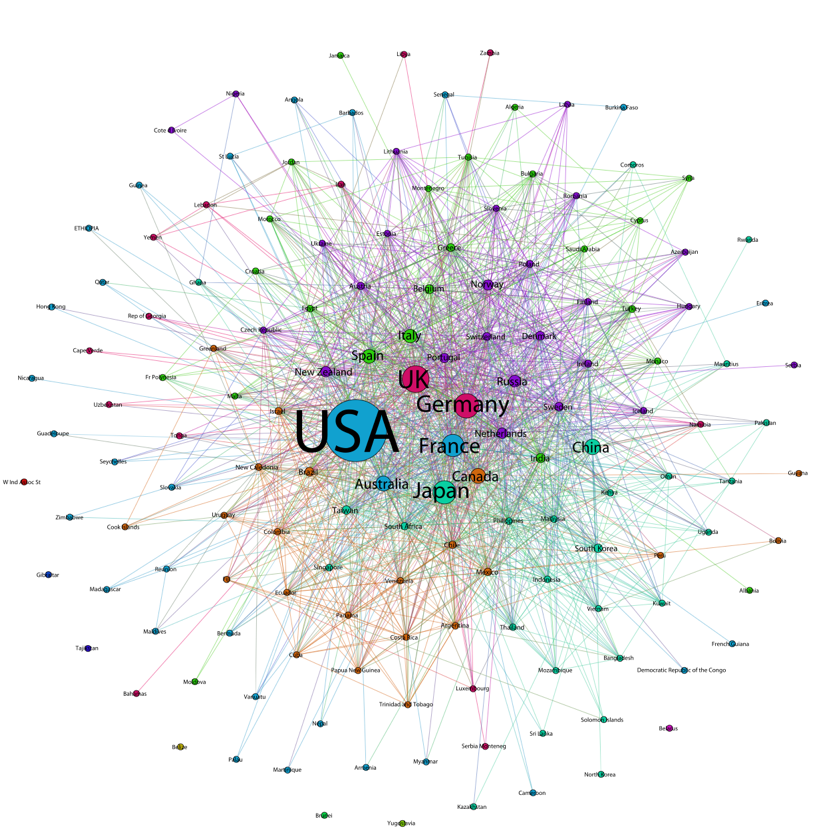

Figure 3.4 provides a network map showing the main linkages between researchers by country based on co-publications.

Figure 3.4: Cross-country Collaboration Network (Author country)

In the case of the UK, researchers have collaborated in publications with other researchers from a total of 97 countries. The top countries with which UK researchers collaborate are the USA, Germany, France, Australia, Canada, Spain, Portugal, Norway and the Netherlands. However, increasing regular collaboration with China is observed from 2008 onwards (41 publications), with Brazil from 2004 onwards (18 records) and South Africa from 2008 onwards (15 records). In addition significant collaboration is observed with researchers in Mexico (20), Chile (19), India (13), Malaysia (10), Panama (10), and Indonesia (9).

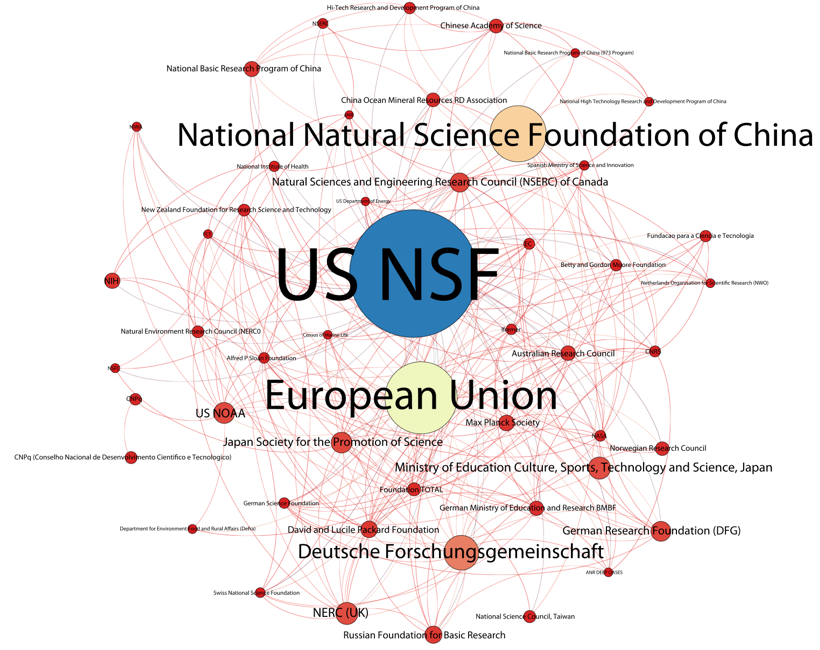

What is significant about this network of relations between researchers is that it reflects underlying investments by countries in the development of marine research capacity and collaborations. It is not presently possible to readily identify levels of investment in research and this remains a topic for future research. However, it is possible to gain an insight into some of the key agencies involved in supporting deep-sea related research. Figure 3.5 presents a network map of the top funding agencies for the overall marine dataset. Note that funding information is mainly confined to records published after 2008 and covers only 24% of the data. The acronym US NSF at the centre of Figure 3.5 stands for United States National Science Foundation.

Figure 3.5: Funding Organisation Network Deep-Sea and Marine Natural Products Research

The visualization of this type of network is important because it reveals the main actors involved in funding deep-sea related research and the connections between funding agencies at the level of published outputs.

In debates on access to genetic resources and benefit-sharing this form of network analysis is relevant because the published outputs of deep-sea research ultimately reflect decision making on financial investments in research. It is here also that what may be considered as non-monetary benefits in the form of research collaborations, training, sharing equipment etc. begin to become evident.

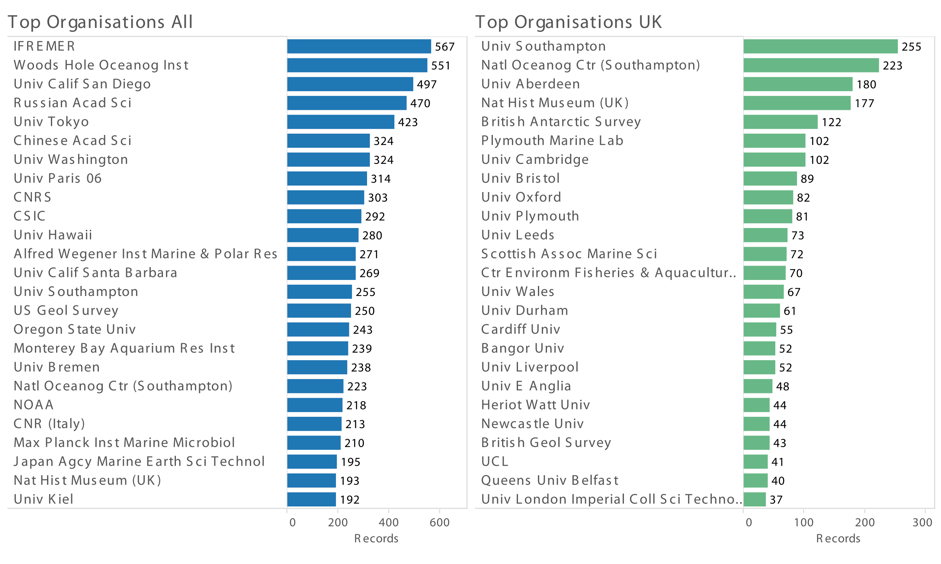

In considering these networks, one possibility to develop benefit-sharing may be to promote greater communication and/or coordination between funding agencies in supporting deep-sea research to avoid unnecessary duplication of effort and also to promote collaboration between researchers in a number of countries. In international terms, across all areas of research, the European Framework Programmes (presently Horizon 2020) that finance consortiums of researchers from EU member states and other countries is probably the single most important example of this type of collaborative experience. One aspect of a potential implementing agreement on access and benefit-sharing in relation to deep-sea research and marine genetic-resources could be strengthened communication and coordination in research funding and establishing research priorities with the participation of deep-sea researchers. Further details on possible components of this idea are provided in the review of expert perspectives in chapter 7. Figure 3.6 presents the top-ranking organisations involved in publications overall, and top UK organisations appearing in the data.

Figure 3.6: Top Research Organisations (Publication Counts)

In considering Figure 3.6 note that author organisations have been subjected to basic cleaning to capture name variants. In the overall data we can clearly see the presence of the University of Southampton, the National Oceanography Centre (Southampton), and the UK Natural History Museum in the top rankings. The UK appears prominently in global scientific publications relating to deep-sea research. This profile will reflect levels of funding for deep-sea research in the UK and the publication culture in UK research organisations.

The top organisations with whom UK researchers collaborate elsewhere in the world include IFREMER (France), the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (USA), researchers at CSIC centres in Spain, the Russian Academy of Sciences, the University of Paris 6 and the University of the Azores (Portugal) among other institutions in 97 countries.

We now turn to research most closely associated with genetic resources and research and development related to potential commercial products. The journal subject categories identified in Figure 3.6 (above) provide a basic rough guide to research publications with potential economic value14. The top ranking organisations include IFREMER, the University of California in San Diego, the Chinese Academy of Science, the Russian Academy of Science and CNRS (France). No UK organisation features in the top 20 for research publications in these categories with the University of Aberdeen and the University of Southampton emerging as the top UK organisations in the global rankings15. Within the data for the UK, the top organisations in these areas are the University of Aberdeen, and the Universities of Southampton, Bristol, Oxford, Kent, Newcastle and the British Antarctic Survey. However, this picture shifts depending on the subject category. For example, Heriot Watt University and the University of Stirling appear with greater prominence in the data for Biotechnology and Applied Microbiology while the Universities of Cambridge and London come increasingly to the fore in Chemistry subject categories.

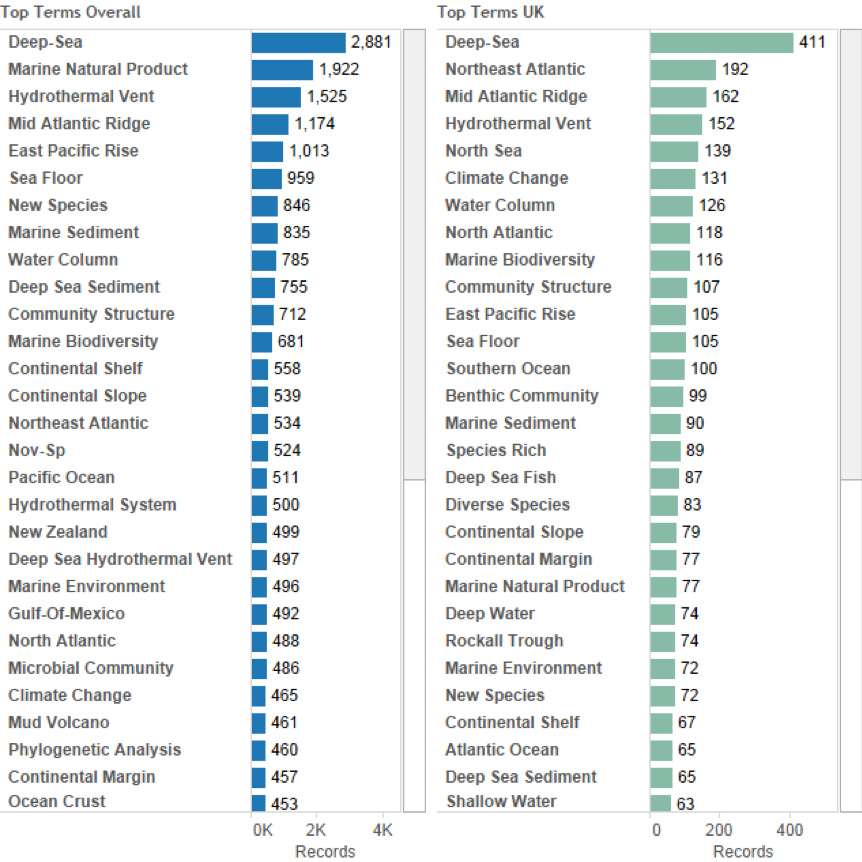

3.0.4 Research Topics and Locations

An insight into the orientation of research can be provided by reviewing the top terms that appear in the title, abstracts or author keywords within the reference dataset. At the outset we would note that the presentation of the data is affected by our original choices of key words in performing the searches notably “deep-sea”, “marine natural products”, “hydrothermal vent” and “marine biodiversity” with a full list provided in Annex 1. Figure 3.7 provides a list of the top multi-word phrases in the data and the same data for UK related publications.

Figure 3.7: Top Terms and Phrases in the Scientific Literature

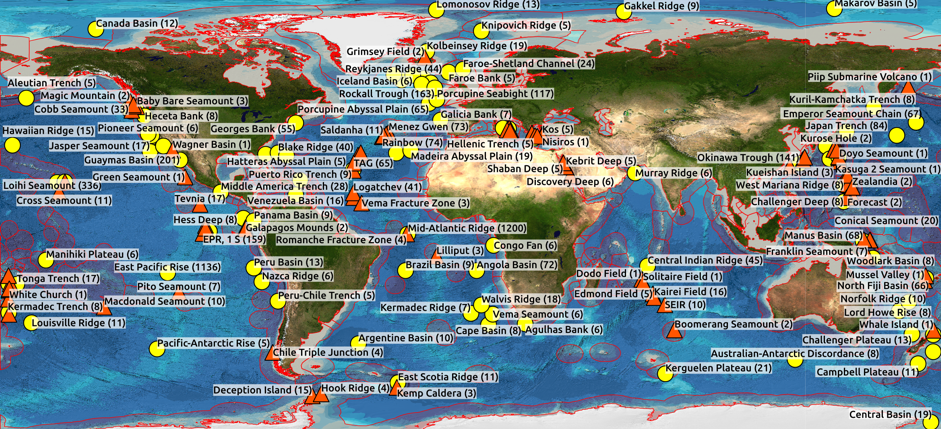

What is striking in Figure 3.7 is not the prominence of terms such as deep-sea or marine natural products that were introduced by our search criteria but the references to places. That is, this data highlights that researchers are concentrating in particular areas. In the case of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, East Pacific Rise or Gulf of Mexico this is likely to involve specifics sites (e.g. the Lucky Strike Vent Field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge). In other cases more general references are made to major oceans, or geographic sections of major oceans. In practice, we suspect, but cannot presently confirm, that further investigation would reveal clusters of research activity around specific places (e.g. the Juan de Fuca Ridge, Guaymas Basin) that would reveal that research effort is not evenly distributed but highly concentrated around specific places. Figure 3.8 displays the same data using the centre of geographical coordinates for large geographical features.

Figure 3.8: Global Concentration of Research Effort in the Deep-Sea

This tendency towards clustering arises because known sites rich in biodiversity are more likely to yield results, produce useful publications and attract more research funding, and because longitudinal studies at the same sites are important in understanding topics such as community structure, succession and environmental impacts over time. However, these same factors will favour charismatic locations, such as hydrothermal vents, and mitigate against wider exploration of unpromising or high-risk areas such as the abyssal plain (see below).

In the case of UK research within our data, the Atlantic, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the North Sea feature prominently as does the East Pacific Rise, presumably as a feature of research collaborations with researchers in the United States. Closer to the UK the Rockall Trough (also known as the Rockall Basin) also features prominently compared with the overall data.

In practice the available data suggests that researchers will concentrate research effort in specific areas and that these areas will logically be those that are in practical terms, the easiest to access on a regular basis. Furthermore, as in the case of UK activity at the East Pacific Rise, international research collaborations will be important, such as with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. In other cases, such as the Southern Ocean, UK capacity in the form of the British Antarctic Survey is joined with capacity elsewhere in Europe, such as the Wegener Institute operating the ship Polarstem, or facilitates research by other researchers from institutions such as the University of Hamburg (Germany) or Ghent (Belgium). That is, international collaboration is of key importance in the planning and realisation of deep-sea marine research but deep-sea research tends to cluster around certain locations.

3.0.5 Conclusions

This chapter has focused on examining trends in marine scientific research in the deep-sea and trends in marine natural products research using a sample of over 24,000 marine scientific publications on the deep-sea and natural products as a guide. A number of observations can now be made regarding the characteristics of marine research in the deep-sea and Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction in connection with a potential implementing agreement within the framework of UNCLOS on access and benefit-sharing. These are as follows:

The available data strongly suggests that marine research in deep-sea locations is concentrated inside the EEZ and a more limited number of locations in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, notably the East Pacific Rise and Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The latter are large geographical features and further work is desirable to refine location analysis;

We believe that research will tend to concentrate in specific locations associated with research success (notably publications) at the expense of expansion into new areas in the absence of other incentives for expansion of research areas;

Strict regulations on access to genetic resources in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction could promote research inside the EEZ at the expense of the expansion of research in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. This suggests that any access regulations for marine scientific research on genetic resources, as opposed to fishing or extractive industrial activity, should be light touch;

International collaboration between research teams and countries with deep-sea infrastructure is a key enabling feature of deep-sea research because of the complexities and costs involved. This suggests a need for greater cooperation and coordination between research teams from different countries as a key means of generating long term benefits for research under any implementing agreement on access and benefit-sharing;

The UK is a top ranking country for deep-sea research but is markedly less prominent in applied commercially oriented research in our data;

Research participation is a key benefit as is access to data. This area could be strengthened based on existing practices and proposals from the deep-sea research community;

The hidden network of cooperation between funding agencies supporting deep-sea research suggests a need for greater communication and coordination such as the creation of a possible road map for research in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction in consultation with the deep-sea research community (see chapter 7);

Consideration should be given to a funding mechanism for ‘risky’ research ventures that provides incentives for exploratory research beyond existing areas of research concentration. Risky in this context does not mean physically dangerous but means dangerous for researchers in career terms based on publications and the ability to attract research funding.

See Annex 1↩

See Annex 1↩

See Annex 1↩

We would emphasise that journal subject categories provide a rough guide because they are developed by Thomson for use in Web of Science and will underplay important publications in major interdisciplinary journals such as Nature and Science.↩

The rankings are affected by variations of organisational names within Web of Science records that require cleaning. The data presented here has been subjected to basic cleaning.↩