3.4 Asymmetric Relations and Directed Graphs

In contrast to spending time together, being members of the same family, or being in the same place at the same time, some social ties allow for inherent directionality. Edges in these graphs are are called asymmetric ties. That is, one member of the pair can claim to have a particular type of social relationship with the other, but it is possible (although not necessary) that the other person fails to have the same relationship with the first. Sentiment relations, such as liking or disliking somebody, are like this. For instance, you can claim to like somebody else, but this does not necessarily mean that that person will return the favor. They may, or they may not. The point is that, in contrast to symmetric tie, mutuality or reciprocity is not built in by definition, but must happen as an empirical event in the world. We need to ask the other person to find out. Can you think of other examples of asymmetric social ties?

Reciprocity is an important concept in the social sciences. Only asymmetric ties may have the property of being non-reciprocal or having more or less reciprocity. If I think you are my friend, I very much hope that you also think you are my friend. Often, sociologists ask: if I do you a favor, would you do me a favor in the future? Additionally, sociologists often ask: if I treat you with respect, will you also treat me with respect? If I text you, will you text me back? If this is true, we have a level of reciprocity in our relationship.

For some ties, such as sentiment (e.g., likes and dislikes) or friendship relations, reciprocity is all or none; it either exists or it does not. For other ties, such as communication ties (e.g., those defined by the amount of texting, or calling), reciprocity is a matter of degree, there may be more or less. In all cases, reciprocity is at a maximum when the content of the relationship is equally exchanged between actors. Can you think of relationships in your life characterized by more or less reciprocity?

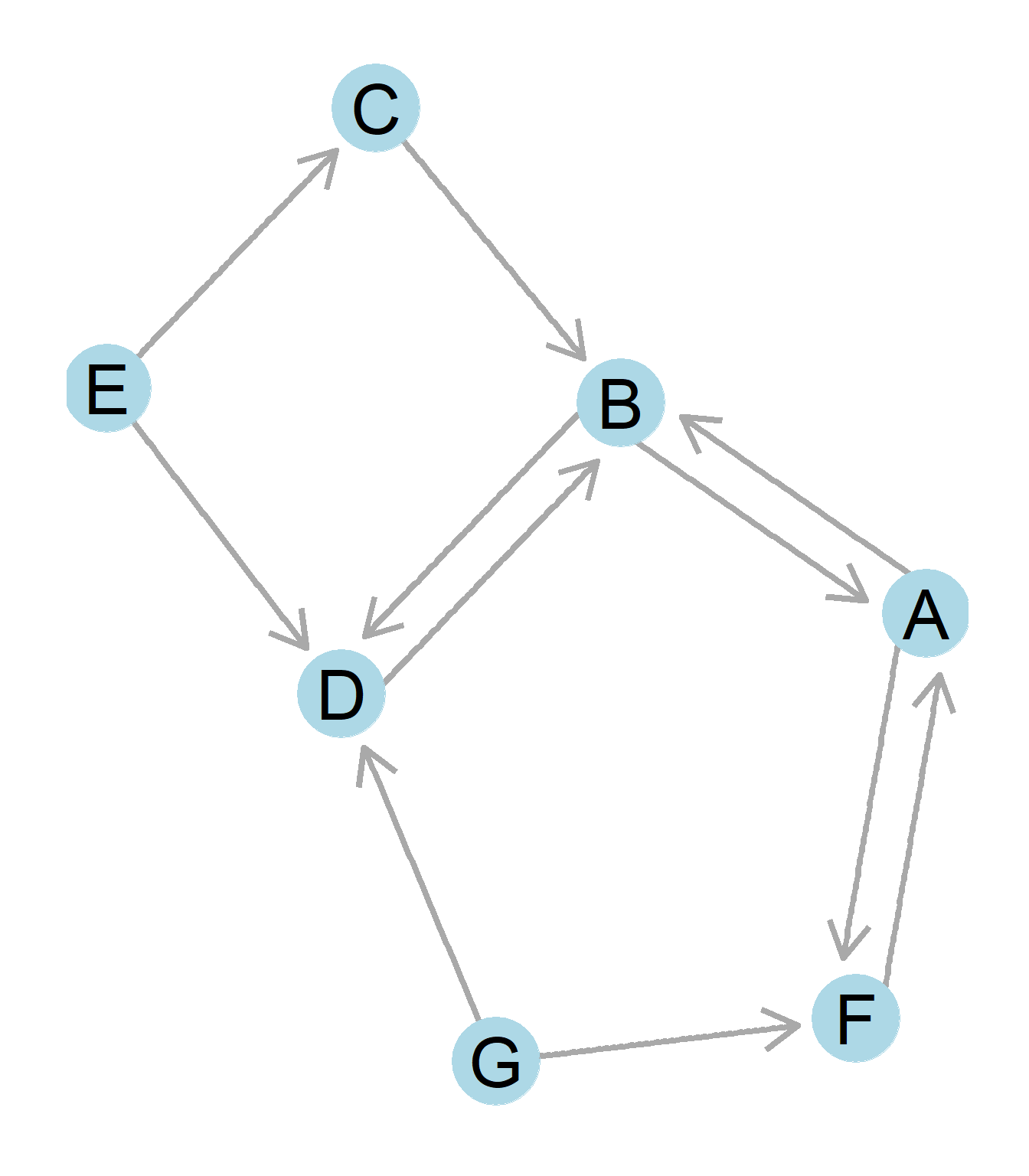

Figure 2.5: A directed graph.

Figure 2.5: A directed graph.

Just like symmetric ties are represented using a particular type of graph (undirected), social networks composed of asymmetric ties are represented using a directed graph. Figure 2.5 shows the point and line diagram picture of a directed graph. What were simple lines for an undirected graph (Figure 2.4) have been replaced with arrows indicating directionality. A node sends a relationship to the node that the arrow points to. Up to two directed arrows may link nodes going both ways.

Thus, in a directed graph, for every edge, there is a source node and a destination node. So in the case of “A likes B” the source node is A and the destination node is B. In the case of “B likes A” the source node is B and the destination node is A. If Figure 2.5 were an advice network(Cross, Borgatti, and Parker 2001Cross, Rob, Stephen P Borgatti, and Andrew Parker. 2001. “Beyond Answers: Dimensions of the Advice Network.” Social Networks 23 (3): 215–35.), on the other hand, we could say that H seeks advice from D, but D does not seek advice from H. This may be because D is higher in the office hierarchy or is more experienced than H, in which case lack of reciprocity may be indicative of an authority relationship between the two nodes.

One must always be careful when examining a directed network to make sure one properly understands the direction of the underlying social relationships.