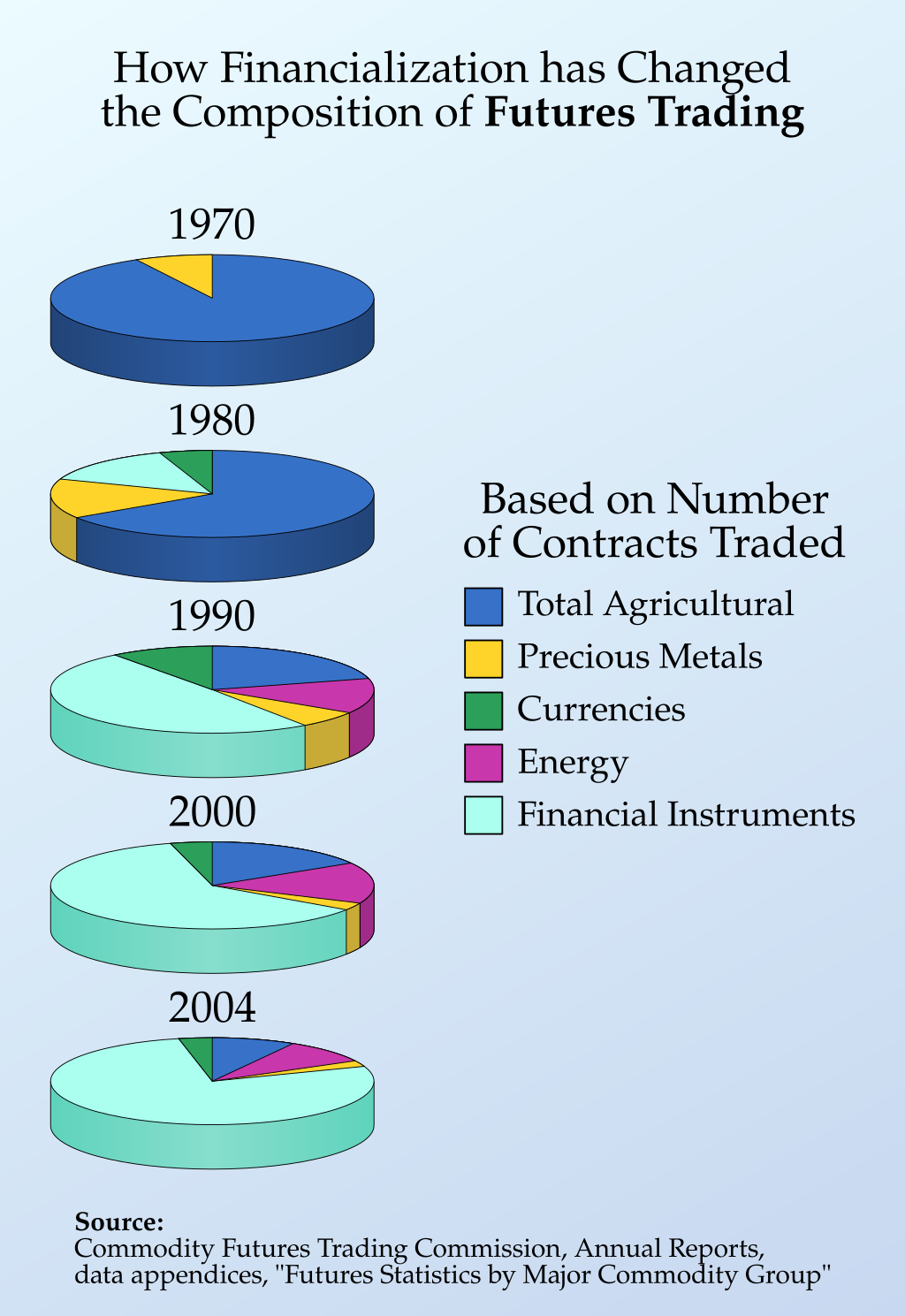

Chapter 3 Financialisation

In the 1970s, the financial sector comprised slightly more than 3% of total GDP of the U.S. economy while total financial assets of all investment banks made up less than 2% of U.S. GDP. The period from the New Deal through the 1970s has been referred to as the era of “boring banking” because banks that took deposits and made loans to individuals were prohibited from engaging in investments involving creative financial engineering and investment banking.

U.S. federal deregulation in the 1980s of many types of banking practices paved the way for the rapid growth in the size, profitability and political power of the financial sector. Such financial sector practices included creating private mortgage-backed securities, and more speculative approaches to creating and trading derivatives based on new quantitative models of risk and value. Wall Street ramped up pressure on the United States Congress for more deregulation, including for the repeal of Glass-Steagall, a New Deal law that, among other things, prohibits a bank that accepts deposits from functioning as an investment bank since the latter entails greater risks.

As a result of this rapid financialisation, the financial sector scaled up vastly in the span of a few decades. In 1978, the financial sector comprised 3.5% of the U.S. GDP, but by 2007 it had reached 5.9%. Financial sector profits grew by 800%, adjusted for inflation, from 1980 to 2005. In comparison with the rest of the economy, U.S. non financial sector profits grew by 250% during the same period.

The securities that were so instrumental in triggering the financial crisis of 2007-2008, asset-backed securities, including collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) were practically non-existent in 1978. By 2007, they comprised $4.5 trillion in assets, equivalent to 32% of U.S. GDP.

3.1 The need for liquidity: markets

Section largely borrowed from Dı́az and Escribano (2020).

In business, economics or investment, market liquidity is a market’s feature whereby an individual or firm can quickly purchase or sell an asset without causing a drastic change in the asset’s price. Liquidity involves the trade-off between the price at which an asset can be sold, and how quickly it can be sold. In a liquid market, the trade-off is mild: one can sell quickly without having to accept a significantly lower price. In a relatively illiquid market, an asset must be discounted in order to sell quickly.Money, or cash, is the most liquid asset because it can be exchanged for goods and services instantly at face value.

During the last three decades, liquidity has been an increasingly relevant concept when valuing financial assets as well as a subject increasingly present in the literature. Despite the large number of articles on the subject, especially in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008, there is a lack of a coherent understanding of what different aspects the concept of liquidity encompasses, what type of measures and proxies are most appropriate to measure each facet, what data and calculation methods they require, what types of results they produce, and under what circumstances. Understanding whether the liquidity measure used in the valuation of an asset is effective is a relevant practical issue for practitioners. The minimum liquidity standards proposed by regulators and international institutions and included in private investment policy statements are also other hot topics that require a good knowledge of the liquidity literature.

Let us review various dimensions of liquidity:

Definition 3.1 (Market breadth) Market breadth concerns the trading volume of the existing orders at different prices. It refers to the possibility that market participants can suffer large price concessions when they want to sell discarded assets. A market is said to be broad when there are numerous buying and seller orders that at the same time present large volumes.

Definition 3.2 (Market depth) Market depth addresses the number of orders around equilibrium prices and is also related to demand pressure and inventory risk. A market is deep when there are numerous buying and seller orders around equilibrium prices.

Definition 3.3 (Market immediacy) Market immediacy is the speed at which the orders are executed in the market. It depends on its demand and supply, i.e. on the willingness of sellers and buyers to trade. Sellers claim and demand immediacy on their willingness to sell, whereas market makers are in charge of placing the immediacy supply. A market is more immediate if transactions between buyers and dealers, or between sellers and dealers can be executed in a brief period of time.

Definition 3.4 (Market resilience) Market resilience deals with a market’s ability to absorb and recover from unexpected asset shocks. A market is resilient if there are many orders to respond to changes in prices and to correct order imbalances derived from asset shocks.

Those different dimensions can be represented as follow:

3.2 The need for protection: regulation

The existence of a system of regulation and supervision is particularly relevant to investors, because it provides access to high quality information, i.e., alleviates the problems of negative selection and moral hazard. There are three key goals that the regulation seeks to achieve:

- Ensuring systemic stability of the financial system, i.e., preventing financial panic that could collapse the entire economy,

- Insurance against monopoly behavior in the financial service providers,

- Investor protection, with emphasis on the most vulnerable target group of small investors.

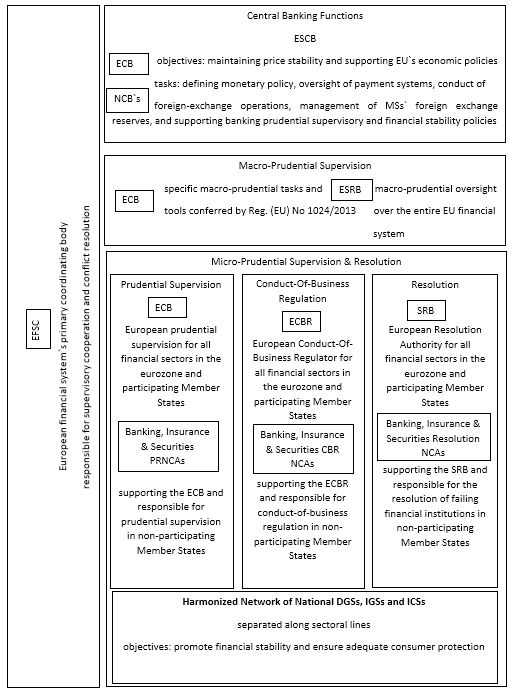

provides a stylised representation of the European Financial System architecture.

Capital requirement Licensing Supervising

3.3 Intermediaries

3.3.1 Banks

A bank is a financial institution that accepts deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital markets.

Because banks play an important role in financial stability and the economy of a country, most jurisdictions exercise a high degree of regulation over banks. Most countries have institutionalised a system known as fractional reserve banking, under which banks hold liquid assets equal to only a portion of their current liabilities.

In addition to other regulations intended to ensure liquidity, banks are generally subject to minimum capital requirements based on an international set of capital standards, the Basel Accords.

The economic functions of banks include:

Issue of money, in the form of banknotes and current accounts subject to cheque or payment at the customer’s order. These claims on banks can act as money because they are negotiable or repayable on demand, and hence valued at par. They are effectively transferable by mere delivery, in the case of banknotes, or by drawing a cheque that the payee may bank or cash.

Netting and settlement of payments – banks act as both collection and paying agents for customers, participating in interbank clearing and settlement systems to collect, present, be presented with, and pay payment instruments. This enables banks to economise on reserves held for settlement of payments since inward and outward payments offset each other. It also enables the offsetting of payment flows between geographical areas, reducing the cost of settlement between them.

Credit quality improvement – banks lend money to ordinary commercial and personal borrowers (ordinary credit quality), but are high quality borrowers. The improvement comes from diversification of the bank’s assets and capital which provides a buffer to absorb losses without defaulting on its obligations. However, banknotes and deposits are generally unsecured; if the bank gets into difficulty and pledges assets as security, to raise the funding it needs to continue to operate, this puts the note holders and depositors in an economically subordinated position.

Asset liability mismatch/Maturity transformation – banks borrow more on demand debt and short term debt, but provide more long-term loans. In other words, they borrow short and lend long. With a stronger credit quality than most other borrowers, banks can do this by aggregating issues (e.g. accepting deposits and issuing banknotes) and redemptions (e.g. withdrawals and redemption of banknotes), maintaining reserves of cash, investing in marketable securities that can be readily converted to cash if needed, and raising replacement funding as needed from various sources (e.g. wholesale cash markets and securities markets).

Money creation/destruction – whenever a bank gives out a loan in a fractional-reserve banking system, a new sum of money is created and conversely, whenever the principal on that loan is repaid money is destroyed.

3.3.1.1 Different types of banks

Banks’ activities can be divided into:

retail banking, dealing directly with individuals and small businesses;

business banking, providing services to mid-market business;

corporate banking, directed at large business entities;

private banking, providing wealth management services to high-net-worth individuals and families;

investment banking, relating to activities on the financial markets.

Most banks are profit-making, private enterprises. However, some are owned by the government, or are non-profit organisations.

Commercial banks: the term used for a normal bank to distinguish it from an investment bank. After the Great Depression, the U.S. Congress required that banks only engage in banking activities, whereas investment banks were limited to capital market activities. Since the two no longer have to be under separate ownership, some use the term “commercial bank” to refer to a bank or a division of a bank that mostly deals with deposits and loans from corporations or large businesses.

Community banks: locally operated financial institutions that empower employees to make local decisions to serve their customers and partners. Community development banks: regulated banks that provide financial services and credit to under-served markets or populations.

Postal savings banks: savings banks associated with national postal systems.

Private banks: banks that manage the assets of high-net-worth individuals. Historically a minimum of US$1 million was required to open an account, however, over the last years, many private banks have lowered their entry hurdles to US$350,000 for private investors.

Savings banks: in Europe, savings banks took their roots in the 19th or sometimes even in the 18th century. Their original objective was to provide easily accessible savings products to all strata of the population. In some countries, savings banks were created on public initiative; in others, socially committed individuals created foundations to put in place the necessary infrastructure. Nowadays, European savings banks have kept their focus on retail banking: payments, savings products, credits, and insurances for individuals or small and medium-sized enterprises. Apart from this retail focus, they also differ from commercial banks by their broadly decentralised distribution network, providing local and regional outreach – and by their socially responsible approach to business and society.

3.3.2 Broker/dealer

In the United States, broker-dealers are regulated under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

The 1934 Act defines “broker” as “any person engaged in the business of effecting transactions in securities for the account of others”, and defines “dealer” as “any person engaged in the business of buying and selling securities for his own account, through a broker or otherwise”. Under either definition, the person must be performing these functions as a business; if conducting similar transactions on a private basis, they are considered a trader and subject to different requirements.

When acting on behalf of customers, broker-dealers have a duty to obtain “best execution” of transactions, which generally means achieving the best economic price under the circumstances

3.4 Markets

This section borrows from Hull (2006).

3.4.1 Exchange Traded Markets

A derivatives exchange is a market where individuals and companies trade standardized contracts that have been defined by the exchange. Derivatives exchanges have existed for a long time. The Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) was established in 1848 to bring farmers and merchants together. Initially its main task was to standardize the quantities and qualities of the grains that were traded. Within a few years, the first futures-type contract was developed. It was known as a to-arrive contract. Speculators soon became interested in the contract and found trading the contract to be an attractive alternative to trading the grain itself. A rival futures exchange, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), was established in 1919. Now futures exchanges exist all over the world. The CME and CBOT have merged to form the CME Group (www.cmegroup.com), which also includes the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), and the Kansas City Board of Trade (KCBT).

The Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE, www.cboe.com) started trading call option contracts on 16 stocks in 1973. Options had traded prior to 1973, but the CBOE succeeded in creating an orderly market with well-defined contracts. Put option contracts started trading on the exchange in 1977. The CBOE now trades options on thousands of stocks and many different stock indices. The underlying assets include foreign currencies and futures contracts as well as stocks and stock indices.

Once two traders have agreed to trade a product offered by an exchange, it is handled by the exchange clearing house. This stands between the two traders and manages the risks. Suppose, for example, that trader A enters into a futures contract to buy 100 ounces of gold from trader B in six months for 1,750 per ounce. The result of this trade will be that A has a contract to buy 100 ounces of gold from the clearing house at $1,750 per ounce in six months and B has a contract to sell 100 ounces of gold to the clearing house for $1,750 per ounce in six months. The advantage of this arrangement is that traders do not have to worry about the creditworthiness of the people they are trading with.

The clearing house takes care of credit risk by requiring each of the two traders to deposit funds (known as margin) with the clearing house to ensure that they will live up to their obligations. Margin requirements and the operation of clearing houses are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

3.4.2 Over The Counter Markets

Not all derivatives trading is on exchanges. Many trades take place in the over-the-counter (OTC) market. Banks, other large financial institutions, fund managers, and corporations are the main participants in OTC derivatives markets. Once an OTC trade has been agreed, the two parties can either present it to a central counterparty (CCP) or clear the trade bilaterally. A CCP is like an exchange clearing house. It stands between the two parties to the derivatives transaction so that one party does not have to bear the risk that the other party will default. When trades are cleared bilaterally, the two parties have usually signed an agreement covering all their transactions with each other. The issues covered in the agreement include the circumstances under which outstanding transactions can be terminated, how settlement amounts are calculated in the event of a termination, and how the collateral (if any) that must be posted by each side is calculated.