Methods: Statistical Methods (12)

The items from STROBE state that you should report:

- Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding (12a) - Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions (12b)

- Explain how missing data were addressed (12c)

- Cohort study If applicable, explain how loss to follow up was addressed (12d)

- Case-control study If applicable, explain how matching of cases and controls was addressed (12d)

- Cross-sectional study If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy (12d)

- Describe any sensitivity analyses (12e)

Some key items to consider adding:

- All statistical methods for each objective at a level of detail sufficient for a knowledgeable reader to replicate the methods

- Clearly indicate the unit of analysis (e.g., individual, team, family, unit, etc.)

- The validity and reliability of any measurements used

- If any internal/external validation was done

- How items/variables were selected/introduced into statistical models

- Data analysis software version and options/settings used

- If the same association under study has previously been published, consider using a similar analysis model and definitions for replicative purposes

- Methods used to

– Assess robustness of analyses (e.g, sensitivity analyses, quantitative bias assessment)

– Adjust for measurement error, (i.e., from a validity or calibration study)

– Account for (complex) sampling strategy (e.g., estimator used)

– Address missing data or loss-to-follow-up

– Control for confounding

– Manage and correct for for non-independence (i.e., relatedness) of data

– Address multiple comparisons or to control for the risk of false positive findings

– Assess and address population stratification

– Identify and address repeated measures on subjects

– Clean data

– Match, combine, or link data (person/individual/dataset level linkages) and an evaluation of the linkage quality

Explanation 12a

In general, there is no one correct statistical analysis but, rather, several possibilities that may address the same question, but make different assumptions. Regardless, investigators should pre-determine analyses at least for the primary study objectives in a study protocol. Often additional analyses are needed, either instead of, or as well as, those originally envisaged, and these may sometimes be motivated by the data. When a study is reported, authors should tell readers whether particular analyses were suggested by data inspection. Even though the distinction between pre-specified and exploratory analyses may sometimes be blurred, authors should clarify reasons for particular analyses.

If groups being compared are not similar with regard to some characteristics, adjustment should be made for possible confounding variables by stratification or by multivariable regression (see box 5). (Slama & Werwatz, 2005) Often, the study design determines which type of regression analysis is chosen. For instance, Cox proportional hazard regression is commonly used in cohort studies, (S, n.d.-b) whereas logistic regression is often the method of choice in case-control studies. (Schlesselman, 1982; WD, 1994). Analysts should fully describe specific procedures for variable selection and not only present results from the final model. (Altman et al., 1983; Clayton & Hills, 1993) If model comparisons are made to narrow down a list of potential confounders for inclusion in a final model, this process should be described. It is helpful to tell readers if one or two covariates are responsible for a great deal of the apparent confounding in a data analysis. Other statistical analyses such as imputation procedures, data transformation, and calculations of attributable risks should also be described. Nonstandard or novel approaches should be referenced and the statistical software used reported. As a guiding principle, we advise statistical methods be described “with enough detail to enable a knowledgeable reader with access to the original data to verify the reported results.” (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, 1997)

In an empirical study, only 93 of 169 articles (55%) reporting adjustment for confounding clearly stated how continuous and multi-category variables were entered into the statistical model. (Müllner et al., 2002) Another study found that among 67 articles in which statistical analyses were adjusted for confounders, it was mostly unclear how confounders were chosen. (Pocock et al., 2004)

Examples 12a

- “The adjusted relative risk was calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel technique, when evaluating if confounding by age or gender was present in the groups compared. The 95% confidence interval (CI) was computed around the adjusted relative risk, using the variance according to Greenland and Robins and Robins et al.” (Berglund et al., 2001; Vandenbroucke et al., 2007).

Explanation 12b

As discussed in detail under item 17, many debate the use and value of analyses restricted to subgroups of the study population. (Gotzsche, 2006; Pocock et al., 2004) Subgroup analyses are nevertheless often done. (Pocock et al., 2004) Readers need to know which subgroup analyses were planned in advance, and which arose while analyzing the data. Also, it is important to explain what methods were used to examine whether effects or associations differed across groups (see item 17).

Interaction relates to the situation when one factor modifies the effect of another (therefore also called ‘effect modification’). The joint action of two factors can be characterized in two ways: on an additive scale, in terms of risk differences; or on a multiplicative scale, in terms of relative risk (see box 8). Many authors and readers may have their own preference about the way interactions should be analyzed. Still, they may be interested to know to what extent the joint effect of exposures differs from the separate effects. There is consensus that the additive scale, which uses absolute risks, is more appropriate for public health and clinical decision making. (Szklo & Nieto, 2000) Whatever view is taken, this should be clearly presented to the reader, as is done in the example above. (Hallan et al., 2006) A lay-out presenting separate effects of both exposures as well as their joint effect, each relative to no exposure, might be most informative. It is presented in the example for interaction under item 17, and the calculations on the different scales are explained in box 8.

Examples 12b

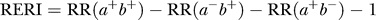

- “Sex differences in susceptibility to the 3 lifestyle-related risk factors studied were explored by testing for biological interaction according to Rothman: a new composite variable with 4 categories (a−b−, a−b+, a+b−, and a+b+) was redefined for sex and a dichotomous exposure of interest where a− and b− denote absence of exposure. RR was calculated for each category after adjustment for age. An interaction effect is defined as departure from additivity of absolute effects, and excess RR caused by interaction (RERI) was calculated:

- where RR(a+b+) denotes RR among those exposed to both factors where RR(a−b−) is used as reference category (RR = 1.0). Ninety-five percent CIs were calculated as proposed by Hosmer and Lemeshow. RERI of 0 means no interaction” (Hallan et al., 2006; Vandenbroucke et al., 2007).

Box 5. Confounding

Confounding literally means confusion of effects. A study might seem to show either an association or no association between an exposure and the risk of a disease. In reality, the seeming association or lack of association is due to another factor that determines the occurrence of the disease but that is also associated with the exposure. The other factor is called the confounding factor or confounder. Confounding thus gives a wrong assessment of the potential ‘causal’ association of an exposure. For example, if women who approach middle age and develop elevated blood pressure are less often prescribed oral contraceptives, a simple comparison of the frequency of cardiovascular disease between those who use contraceptives and those who do not, might give the wrong impression that contraceptives protect against heart disease.

Investigators should think beforehand about potential confounding factors. This will inform the study design and allow proper data collection by identifying the confounders for which detailed information should be sought. Restriction or matching may be used. In the example above, the study might be restricted to women who do not have the confounder, elevated blood pressure. Matching on blood pressure might also be possible, though not necessarily desirable (see Box 2). In the analysis phase, investigators may use stratification or multivariable analysis to reduce the effect of confounders. Stratification consists of dividing the data in strata for the confounder (e.g., strata of blood pressure), assessing estimates of association within each stratum, and calculating the combined estimate of association as a weighted average over all strata. Multivariable analysis achieves the same result but permits one to take more variables into account simultaneously. It is more flexible but may involve additional assumptions about the mathematical form of the relationship between exposure and disease.

Taking confounders into account is crucial in observational studies, but readers should not assume that analyses adjusted for confounders establish the ‘causal part’ of an association. Results may still be distorted by residual confounding (the confounding that remains after unsuccessful attempts to control for it (Olsen & Basso, 1999), random sampling error, selection bias and information bias (see Box 3).

Explanation 12c

Missing data are common in observational research. Questionnaires posted to study participants are not always filled in completely, participants may not attend all follow-up visits and routine data sources and clinical databases are often incomplete. Despite its ubiquity and importance, few papers report in detail on the problem of missing data. (Tooth et al., 2005; Vach & Blettner, 1991) Investigators may use any of several approaches to address missing data. We describe some strengths and limitations of various approaches in box 6. We advise that authors report the number of missing values for each variable of interest (exposures, outcomes, confounders) and for each step in the analysis. Authors should give reasons for missing values if possible, and indicate how many individuals were excluded because of missing data when describing the flow of participants through the study (see also item 13). For analyses that account for missing data, authors should describe the nature of the analysis (eg, multiple imputation) and the assumptions that were made (eg, missing at random, see box 6). (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007)

Examples 12c

- “Our missing data analysis procedures used missing at random (MAR) assumptions. We used the MICE (multivariate imputation by chained equations) method of multiple multivariate imputation in STATA. We independently analysed 10 copies of the data, each with missing values suitably imputed, in the multivariate logistic regression analyses. We averaged estimates of the variables to give a single mean estimate and adjusted standard errors according to Rubin’s rules” (Chandola et al., 2006; Vandenbroucke et al., 2007).

Explanation 12d Cohort

Cohort studies are analyzed using life table methods or other approaches that are based on the person-time of follow- up and time to developing the disease of interest. Among individuals who remain free of the disease at the end of their observation period, the amount of follow-up time is assumed to be unrelated to the probability of developing the outcome. This will be the case if follow-up ends on a fixed date or at a particular age. Loss to follow-up occurs when participants withdraw from a study before that date. This may hamper the validity of a study if loss to follow-up occurs selectively in exposed individuals, or in persons at high risk of developing the disease (‘informative censoring’). In the example above, patients lost to follow-up in treatment programs with no active follow-up had fewer CD4 helper cells than those remaining under observation and were therefore at higher risk of dying. (Braitstein et al., 2006)

It is important to distinguish persons who reach the end of the study from those lost to follow-up. Unfortunately, statistical software usually does not distinguish between the two situations: in both cases follow-up time is automatically truncated (‘censored’) at the end of the observation period. Investigators therefore need to decide, ideally at the stage of planning the study, how they will deal with loss to follow-up. When few patients are lost, investigators may either exclude individuals with incomplete follow-up, or treat them as if they withdrew alive at either the date of loss to follow-up or the end of the study. We advise authors to report how many patients were lost to follow-up and what censoring strategies they used.

Box 6. Missing data

Problems and possible solutions

A common approach to dealing with missing data is to restrict analyses to individuals with complete data on all variables required for a particular analysis. Although such ‘complete-case’ analyses are unbiased in many circumstances, they can be biased and are always inefficient (Little & Rubin, 2002). Bias arises if individuals with missing data are not typical of the whole sample. Inefficiency arises because of the reduced sample size for analysis.

Using the last observation carried forward for repeated measures can distort trends over time if persons who experience a foreshadowing of the outcome selectively drop out (Ware, 2009). Inserting a missing category indicator for a confounder may increase residual confounding (Vach & Blettner, 1991). Imputation, in which each missing value is replaced with an assumed or estimated value, may lead to attenuation or exaggeration of the association of interest, and without the use of sophisticated methods described below may produce standard errors that are too small.

Rubin developed a typology of missing data problems, based on a model for the probability of an observation being missing (Little & Rubin, 2002; Rubin, 1976). Data are described as missing completely at random (MCAR) if the probability that a particular observation is missing does not depend on the value of any observable variable(s). Data are missing at random (MAR) if, given the observed data, the probability that observations are missing is independent of the actual values of the missing data. For example, suppose younger children are more prone to missing spirometry measurements, but that the probability of missing is unrelated to the true unobserved lung function, after accounting for age. Then the missing lung function measurement would be MAR in models including age. Data are missing not at random (MNAR) if the probability of missing still depends on the missing value even after taking the available data into account. When data are MNAR valid inferences require explicit assumptions about the mechanisms that led to missing data.

Methods to deal with data missing at random (MAR) fall into three broad classes (Little & Rubin, 2002; Schafer, 1997): likelihood-based approaches (Lipsitz et al., 1999), weighted estimation (Rotnitzky & Robins, 1997) and multiple imputation (DB, 1987; Little & Rubin, 2002). Of these three approaches, multiple imputation is the most commonly used and flexible, particularly when multiple variables have missing values (Barnard & Meng, 1999). Results using any of these approaches should be compared with those from complete case analyses, and important differences discussed. The plausibility of assumptions made in missing data analyses is generally unverifiable. In particular it is impossible to prove that data are MAR, rather than MNAR. Such analyses are therefore best viewed in the spirit of sensitivity analysis (see items 12e and 17). (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007)

Explanation 12d Case-Control

In individually matched case-control studies a crude analysis of the odds ratio, ignoring the matching, usually leads to an estimation that is biased towards unity (see box 2). A matched analysis is therefore often necessary. This can intuitively be understood as a stratified analysis: each case is seen as one stratum with his or her set of matched controls. The analysis rests on considering whether the case is more often exposed than the controls, despite having made them alike regarding the matching variables. Investigators can do such a stratified analysis using the Mantel-Haenszel method on a ‘matched’ 2 by 2 table. In its simplest form the odds ratio becomes the ratio of pairs that are discordant for the exposure variable. If matching was done for variables like age and sex that are universal attributes, the analysis needs not retain the individual, person-to-person matching: a simple analysis in categories of age and sex is sufficient. (K. J. Rothman et al., 1998b) For other matching variables, such as neighborhood, sibship, or friendship, however, each matched set should be considered its own stratum. In individually matched studies, the most widely used method of analysis is conditional logistic regression, in which each case and their controls are considered together. The conditional method is necessary when the number of controls varies among cases, and when, in addition to the matching variables, other variables need to be adjusted for. To allow readers to judge whether the matched design was appropriately taken into account in the analysis, we recommend that authors describe in detail what statistical methods were used to analyse the data. If taking the matching into account does have little effect on the estimates, authors may choose to present an unmatched analysis. (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007)

Explanation 12d Cross-sectional

Most cross-sectional studies use a pre-specified sampling strategy to select participants from a source population. Sampling may be more complex than taking a simple random sample, however. It may include several stages and clustering of participants (eg, in districts or villages). Proportionate stratification may ensure that subgroups with a specific characteristic are correctly represented. Disproportionate stratification may be useful to over-sample a subgroup of particular interest.

An estimate of association derived from a complex sample may be more or less precise than that derived from a simple random sample. Measures of precision such as standard error or confidence interval should be corrected using the design effect, a ratio measure that describes how much precision is gained or lost if a more complex sampling strategy is used instead of simple random sampling. (Lohr, 1999) Most complex sampling techniques lead to a decrease of precision, resulting in a design effect greater than 1.

We advise that authors clearly state the method used to adjust for complex sampling strategies so that readers may understand how the chosen sampling method influenced the precision of the obtained estimates. For instance, with clustered sampling, the implicit trade-off between easier data collection and loss of precision is transparent if the design effect is reported. In the example, the calculated design effects of 1.9 for men indicates that the actual sample size would need to be 1.9 times greater than with simple random sampling for the resulting estimates to have equal precision. (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007)

Explanation 12e

Sensitivity analyses are useful to investigate whether or not the main results are consistent with those obtained with alternative analysis strategies or assumptions. (K. Rothman & Greenland, 1998a) Issues that may be examined include the criteria for inclusion in analyses, the definitions of exposures or outcomes, (Custer et al., 2006) which confounding variables merit adjustment, the handling of missing data, (Dunn et al., 2001; Wakefield et al., 2000) possible selection bias or bias from inaccurate or inconsistent measurement of exposure, disease and other variables, and specific analysis choices, such as the treatment of quantitative variables (see item 11). Sophisticated methods are increasingly used to simultaneously model the influence of several biases or assumptions. (Greenland, 2003; Lash & Fink, 2003; Phillips, 2003)

In 1959 Cornfield et al famously showed that a relative risk of 9 for cigarette smoking and lung cancer was extremely unlikely to be due to any conceivable confounder, since the confounder would need to be at least nine times as prevalent in smokers as in non-smokers. (Cornfield et al., 1959) This analysis did not rule out the possibility that such a factor was present, but it did identify the prevalence such a factor would need to have. The same approach was recently used to identify plausible confounding factors that could explain the association between childhood leukemia and living near electric power lines. (Langholz, 2001) More generally, sensitivity analyses can be used to identify the degree of confounding, selection bias, or information bias required to distort an association. One important, perhaps under recognized, use of sensitivity analysis is when a study shows little or no association between an exposure and an outcome and it is plausible that confounding or other biases toward the null are present. (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007)

Field-specific guidance

Genetic association studies (Little et al., 2009)

- State whether Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was considered and, if so, how

- Describe any methods used for inferring genotypes or haplotypes

Nutritional data (Lachat et al., 2016)

- Describe and justify the method for energy adjustments, intake modeling, and use of weighting factors, if applicable

Response-driven sampling (White et al., 2015)

- Report any criteria used to support statements on whether estimator conditions or assumptions were appropriate

- Explain how seeds were handled in analysis

Rheumatology(Zavada et al., 2014)

- Define and justify the risk window. Whenever possible, categorise as (1) on drug, (2) on drug + lag window or (3) ever treated

- The use of multiple risk attribution models and lag windows is encouraged if appropriate, but needs to be accompanied by a description of numbers and relative risks for each model

Routinely collected health data (Benchimol et al., 2015)

- Authors should describe the extent to which the investigators had access to the database population used to create the study population

Seroepidemiologic studies for influenza (Horby et al., 2017)

- If relevant, report methods used to account for the probability of seropositivity or seroconversion if infected, and to account for decay in antibody titers over time

- Describe the sample type—serum or plasma. If plasma is used, specify the anticoagulant used (heparin, sodium citrate, EDTA, etc.)

- Describe the specimen storage conditions (4°C, −20 °C, −80 °C). If frozen prior to the analysis, describe the time to freezing and the number of freeze/thaw cycles prior to testing

- Specify the assay type (e.g., hemagglutination inhibition; virus neutralization/microneutralization; ELISA; other) and methods used to determine the endpoint titer

- Reference a previously published, CONSISE consensus serologic assay or WHO protocol if used, and any modifications of the protocol. If a previously published protocol is not used, provide full details in supplementary materials

- State what is known about the determinants of the variability of the antibody detection assay being used

- Specify the antigen(s) used in the assay, including virus strain name, subtype, lineage or clade, with standardized nomenclature and reference; specify whether live virus or inactivated virus was used (where applicable)

- Report if antigen(s) from potentially cross-reactive pathogens/strains were used in order to identify cross-reactivity, and specify which antigen was used, including virus name, subtype, strain, lineage and clade, with standardized nomenclature and reference

- If red blood cells were used for a hemagglutinin inhibition assay, specify the animal species from which they were obtained and concentration (v/v) used

- Describe positive and negative controls used

- Describe starting and end dilutions

- Specify laboratory biosafety conditions

- Specify whether replication was performed, and if so, the acceptable replication parameters

- Specify whether a confirmatory assay was performed and all specifics of this assay, at the same level of detail

- Specify international standards used, if appropriate

Resources

References

Altman, D. G., Gore, S. M., Gardner, M. J., & Pocock, S. J. (1983). Statistical guidelines for contributors to medical journals. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 286(6376), 1489–1493. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1547706/

Barnard, J., & Meng, X.-L. (1999). Applications of multiple imputation in medical studies: From AIDS to NHANES. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 8(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/096228029900800103

Benchimol, E. I., Smeeth, L., Guttmann, A., Harron, K., Moher, D., Petersen, I., Sorensen, H. T., Elm, E. von, Langan, S. M., & Committee, R. W. (2015). The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLOS Medicine, 12(10), e1001885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885

Berglund, A., Alfredsson, L., Jensen, I., Cassidy, J. D., & Nygren, A. (2001). The association between exposure to a rear-end collision and future health complaints. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(8), 851–856. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895435600003693

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1997). Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ, 314(7080), 572. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572

Braitstein, P., Brinkhof, M., Dabis, F., Schecter, M., Boulle, A., Miotti, P., Wood, R., Laurent, C., Sprinz, E., Seyler, C., Bangsberg, D., Balestre, E., Sterne, J., May, M., Egger, M., & undefined. (2006). Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: Comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet (London, England), 367(9513), 817–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68337-2

British Medical Journal Publishing. (2018). How to estimate the effect of treatment duration on survival outcomes using observational data. BMJ, 360, k182. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k182

Chandola, T., Brunner, E., & Marmot, M. (2006). Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: Prospective study. BMJ, 332(7540), 521–525. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38693.435301.80

Clayton, D., & Hills, M. (1993). Models for dose-response (chapter 25). In Statistical models in epidemiology (pp. 249–260). Oxford University Press.

Cornfield, J., Haenszel, W., Hammond, E. C., Lilienfeld, A. M., Shimkin, M. B., & Wynder, E. L. (1959). Smoking and Lung Cancer: Recent Evidence and a Discussion of Some Questions. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 22(1), 173–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/22.1.173

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Custer, B., Longstreth, W., Phillips, L. E., Koepsell, T. D., & Van Belle, G. (2006). Hormonal exposures and the risk of intracranial meningioma in women: A population-based case-control study. BMC Cancer, 6(1), 152. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-6-152

DB, R. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley.

Dunn, N. R., Arscott, A., & Thorogood, M. (2001). The relationship between use of oral contraceptives and myocardial infarction in young women with fatal outcome, compared to those who survive: Results from the MICA case-control study. Contraception, 63(2), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00172-X

Gamble, C., Krishan, A., Stocken, D., Lewis, S., Juszczak, E., Dore, C., Williamson, P. R., Altman, D. G., Montgomery, A., Lim, P., Berlin, J., Senn, S., Day, S., Barbachano, Y., & Loder, E. (2017). Guidelines for the Content of Statistical Analysis Plans in Clinical Trials. JAMA, 318(23), 2337–2343. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.18556

Gotzsche, P. (2006). Believability of relative risks and odds ratios in abstracts: Cross sectional study. BMJ, 333, 231–234. https://www.bmj.com/content/333/7561/231?etoc%253E=

Greenland, S. (2003). The Impact of Prior Distributions for Uncontrolled Confounding and Response Bias. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 98(461), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1198/01621450338861905

Greenland, S., Senn, S. J., Rothman, K. J., Carlin, J. B., Poole, C., Goodman, S. N., & Altman, D. G. (2016). Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: A guide to misinterpretations. European Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0149-3

Hallan, S., Mutsert, R. de, Carlsen, S., Dekker, F. W., Aasarød, K., & Holmen, J. (2006). Obesity, Smoking, and Physical Inactivity as Risk Factors for CKD: Are Men More Vulnerable? American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 47(3), 396–405. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.11.027

Horby, P. W., Laurie, K. L., Cowling, B. J., Engelhardt, O. G., Sturm-Ramirez, K., Sanchez, J. L., Katz, J. M., Uyeki, T. M., Wood, J., Van Kerkhove, M. D., & the CONSISE Steering Committee. (2017). CONSISE statement on the reporting of Seroepidemiologic Studies for influenza (ROSES-I statement): An extension of the STROBE statement. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 11(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12411

Ibrahim, J. G., & Molenberghs, G. (2009). Missing data methods in longitudinal studies: A review. Test, 18(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11749-009-0138-x

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. (1997). Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals. In N Engl J Med (Vol. 336, pp. 309–315). http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/

Knol, M. J., Egger, M., Scott, P., Geerlings, M. I., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2009). When One Depends on the Other: Reporting of Interaction in Case-Control and Cohort Studies. Epidemiology, 20(2), 161. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818f6651

Lachat, C., Hawwash, D., Ocké, M. C., Berg, C., Forsum, E., Hörnell, A., Larsson, C., Sonestedt, E., Wirfält, E., Åkesson, A., Kolsteren, P., Byrnes, G., De Keyzer, W., Van Camp, J., Cade, J. E., Slimani, N., Cevallos, M., Egger, M., & Huybrechts, I. (2016). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology—Nutritional Epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An Extension of the STROBE Statement. PLOS Medicine, 13(6), e1002036. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002036

Langholz, B. (2001). Factors that explain the power line configuration wiring code–childhood leukemia association: What would they look like? Bioelectromagnetics, 22(S5), S19–S31. https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-186X(2001)22:5+<::AID-BEM1021>3.0.CO;2-I

Lash, T. L., & Fink, A. K. (2003). Semi-Automated Sensitivity Analysis to Assess Systematic Errors in Observational Data. Epidemiology, 14(4), 451–458. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3703797

Lesko, C. R., Edwards, J. K., Cole, S. R., Moore, R. D., & Lau, B. (2018). When to Censor? American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(3), 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx281

Lipsitz, S. R., Ibrahim, J. G., Chen, M.-H., & Peterson, H. (1999). Non-ignorable missing covariates in generalized linear models. Statistics in Medicine, 18(17-18), 2435–2448. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990915/30)18:17/18<2435::AID-SIM267>3.0.CO;2-B

Little, J., Higgins, J. P. T., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Moher, D., Gagnon, F., Elm, E. von, Khoury, M. J., Cohen, B., Davey-Smith, G., Grimshaw, J., Scheet, P., Gwinn, M., Williamson, R. E., Zou, G. Y., Hutchings, K., Johnson, C. Y., Tait, V., Wiens, M., Golding, J., … Birkett, N. (2009). STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA)— An Extension of the STROBE Statement. PLOS Med, 6(2), e1000022. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000022

Little, R., & Rubin, D. (2002). A taxonomy of missing-data methods (chapter 1.4). In Statistical analysis with missing data (pp. 19–23). Wiley.

Lohr, S. (1999). Design effects (chapter 7.5). In Sampling: Design and analysis. Duxbury Press.

Mansournia, M. A., Etminan, M., Danaei, G., Kaufman, J. S., & Collins, G. (2017). Handling time varying confounding in observational research. BMJ, 359. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4587

Müllner, M., Matthews, H., & Altman, D. G. (2002). Reporting on Statistical Methods To Adjust for Confounding: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136(2), 122. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00009

Olsen, J., & Basso, O. (1999). Re: Residual confounding. American Journal of Epidemiology, 149(290).

Phillips, C. V. (2003). Quantifying and Reporting Uncertainty from Systematic Errors. Epidemiology, 14(4), 459–466. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3703798

Pocock, S. J., Collier, T. J., Dandreo, K. J., Stavola, B. L. de, Goldman, M. B., Kalish, L. A., Kasten, L. E., & McCormack, V. A. (2004). Issues in the reporting of epidemiological studies: A survey of recent practice. The BMJ, 329(7471), 883. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38250.571088.55

Rothman, K., & Greenland, S. (1998a). Basic methods for sensitivity analysis and external adjustment. In Modern epidemiology (2nd ed., pp. 120–125). Lippincott Raven.

Rothman, K. J., Lash, T. L., & Greenland, S. (1998b). Matching. In Modern Epidemiology (2nd ed., pp. 147–161). LWW.

Rotnitzky, A., & Robins, J. (1997). Analysis of Semi-Parametric Regression Models with Non-Ignorable Non-Response. Statistics in Medicine, 16(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19970115)16:1<81::AID-SIM473>3.0.CO;2-0

Rubin, D. B. (1976). Inference and missing data. Biometrika, 63(3), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/63.3.581

S, G. (n.d.-b). Introduction to regression modelling (chapter 21)). In Modern Epidemiology (2nd ed., pp. 401–432). Lippincott Raven.

Schafer, J. (1997). Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman & Hall.

Schlesselman, J. (1982). Logistic regression of case-control studies (chapter 8.2). In Case-control studies design, conduct, analysis (pp. 235–241). Oxford University Press.

Slama, R., & Werwatz, A. (2005). Controlling for continuous confounding factors: Non- and semiparametric approaches. Revue d’Epidemiologie et de Sante Publique, 53, 65–80. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0398762005847698

Smeden, M. van, Lash, T. L., & Groenwold, R. H. H. (2019). Reflection on modern methods: Five myths about measurement error in epidemiological research. International Journal of Epidemiology, dyz251. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz251

Smeden, M. van, Moons, K. G., Groot, J. A. de, Collins, G. S., Altman, D. G., Eijkemans, M. J., & Reitsma, J. B. (2018). Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 0962280218784726. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280218784726

Szklo, M., & Nieto, J. (2000). Communicating results of epidemiologic studies (chapter 9). In Epidemiology, Beyond the Basics (pp. 408–430). Jones; Bartlett.

Tooth, L., Ware, R., Bain, C., Purdie, D. M., & Dobson, A. (2005). Quality of Reporting of Observational Longitudinal Research. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161(3), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi042

Vach, W., & Blettner, M. (1991). Biased Estimation of the Odds Ratio in Case-Control Studies due to the Use of Ad Hoc Methods of Correcting for Missing Values for Confounding Variables. American Journal of Epidemiology, 134(8), 895–907. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116164

Vandenbroucke, J. P., Elm, E. von, Altman, D. G., Gotzsche, P. C., Mulrow, C. D., Pocock, S. J., Poole, C., Schlesselman, J. J., & Egger, M. (2007). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. Epidemiology, 18(6), 805–835. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511

Wakefield, M. A., Chaloupka, F. J., Kaufman, N. J., Orleans, C. T., Barker, D. C., & Ruel, E. E. (2000). Effect of restrictions on smoking at home, at school, and in public places on teenage smoking: Cross sectional study. BMJ, 321(7257), 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7257.333

Ware, J. H. (2009). Interpreting Incomplete Data in Studies of Diet and Weight Loss. Http://Dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe030054. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe030054

WD, T. (1994). Statistical analysis of case-control studies. - Abstract - Europe PMC. In Epidemiol Rev. https://europepmc.org/article/med/7925726

White, R. G., Hakim, A. J., Salganik, M. J., Spiller, M. W., Johnston, L. G., Kerr, L., Kendall, C., Drake, A., Wilson, D., Orroth, K., Egger, M., & Hladik, W. (2015). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology for respondent-driven sampling studies: "STROBE-RDS" statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68(12), 1463–1471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.002

Zavada, J., Dixon, W. G., & Askling, J. (2014). Launch of a checklist for reporting longitudinal observational drug studies in rheumatology: A EULAR extension of STROBE guidelines based on experience from biologics registries. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 73(3), 628. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204102