Chapter 6 Student Research Symposium

6.1 Student Preparation for Symposium

Students took the suggestions provided by scientists, made necessary revisions to their investigation approach, and completed their investigations at school. The assistance educators provided at this step of the project varied by the needs of the students within and among classes. We provided educators with support and suggestions for ways to make effective data visualizations and scientific conference posters to assist in the students completion of this aspect of the project. We also provided logo files that the stydents needed to include on their final poster’s acknowledgements section, based on the funding sources for the year of the project.

The implementation of the final stages of the project varied among school districts. Some schools had all of their students participate in the project with an in-school science showcase to share their work. The showcase was used to decide which groups attended the statewide event - Sci-I Project Student Research Symposium (SRS). Other schools a priori decided which students would be allowed to create and present a poster. Finally, other schools conducted a school vote on which groups should make posters and represent their school. We left this aspect up to the discretion of the educators to add more flexibility into the project, which we found aided in their full participation throughout the year.

6.2 Approach to SRS - Desired Outcomes & Strategy of Agenda

The Student Research Symposium was the culminating event in the year-long project. We hoped participation in the event would continue to build the students agency and “identity” as a scientist. While not all students were able to attend the SRS event, our evaluation results indicated that participating in the project led to these characteristics for all students (see Seeing the Impact of the Sci-I Project):

Student participants at the SRS:

- Felt heard and validated as scientists for their work,

- Gained feedback on their research results/approach/question and/or science communication style, and

- Met real scientists and got their personal questions about science and science careers answered.

Participating scientists benefited from the SRS by:

- Gaining experience communicating with non-expert audiences,

- Seeing what students are capable of doing, and/or

- Learning some of the limitations that K-12 system has when teaching about science as well as the incredible work that teachers put in to overcome those limitations.

The emphasis of the SRS was on students presenting their research to science experts. The intention was not to grade or critique the students’ accomplishments, but rather to engage with the students as scientist peers (albeit scientists in training). Therefore, it was not important that scientists be within the field of research of the students’ investigations. Instead, it was more important that the student-scientist conversation was on the process of conducting the investigation.

The SRS events created an opportunity for a wide range of students to see that scientists are real and approachable people. Approximately 5-7 scientists including graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, technicians, early- and late-career stage faculty, and non-academic professionals participated in an afternoon panel to represent a range of career paths and a diversity of interests in science. We welcomed students onto university campuses to increase their familiarity with their local university and to elevate the importance of the students’ work beyond just a Science Fair at their school.

6.3 Preparing Scientists for the SRS Event

We invited the scientists to come to the event early in the day to help them orient to the event. We stressed the following:

- The Poster Session was not a competition but rather modeled after a poster session at a scientific conference. Scientists were asked not to criticize or critique the student’s research approach or findings but rather to ask lots of questions to help the students grow in their understanding of the process of science.

- We asked the scientists to think back to what it was like to be in grades 6-9! Scientists were asked to remember that the students had a more limited knowledge of the world, experience answering questions with data, and exposure to the process of science.

- We shared active learning and conversation strategies to help the scientists effectively communicate with the students.

We used the following strategies to increase connection to and engagement between scientists, educators, and students.

- Paired a scientist with a school when the students arrived to talk and mingle with the educator and students before the event starts.

- Assignd each scientist approximately four student investigation projects to review. This gave them enough time to really talk and discuss the projects with students, rather than racing through multiple projects within the time alloted.

- Encouraged the scientists to seek out opportunities to talk with participating teachers and students throughout the all parts of the event.

6.4 Preparation & Logistics

Hosting a large number of minors from a range of schools for this event came with a significant amount of logistics and preparation as well as resources (Table 3).

Table 2. Summary of the budgetary components of the SRS in 2017 including roughly 12 participating scientists.

| Component | Range |

|---|---|

| Travel (air, mileage, etc.) of participating scientists | $1,000-1,500 |

| Hotel accommodations of participants and staff | $500-750 |

| Room rental | $500-1,500 |

| Food for participating scientists and staff | $750-1,500 |

| Event materials | $250-500 |

6.4.1 Venue

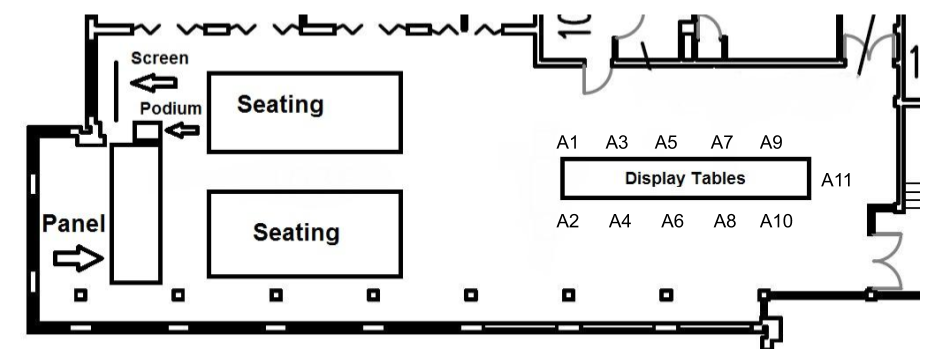

We found having the 100-200 students sitting in chairs during the introductory session and Scientist Panel helped them pay more attention and take the event seriously more as professionals than as kids. It was helpful to have the room to set up so that multiple tables were in one part of the room for many students, educators, and scientists to easily walk around during the Student Poster Session. Ideally we aimed to have a large screen, and supporting projector, and one end of the room to be able to project images of the scientists and agenda/instructions for students (see Event Description for more information). We ensured that the room had a podium with a microphone, microphones for the panelists, and 1-2 handheld microphones to use in the audience for questions. An example of our room set up and location of the posters from the Ohio 2018 SRS is included in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Room layout and set up for the Ohio 2018 Student Reserach Symposium.

6.4.2 Food

Educators, chaperones, and students brought their own lunches to the event. However, we provided coffee and pastries as well as a catered lunch for participating scientists at the event (an example menu from the 2018 Ohio SRS event can be accessed here). This was a small way to show our appreciation of the scientists for taking time out of their day to support the young scientists and our educational project.

6.4.3 Transportation and parking

The majority of our schools provided their own transportation to/from the SRS event. However, we worked with any school who needed help to find funding for transportation if it was a barrier to participating in the event.

We also worked with the local parking office to acquire the necessary parking permissions prior to the event, so that all participants have the necessary permissions. This often required us to have a sense of how many personal cars, vans, and/or buses would be arriving at the hosting location for the SRS. If required by the hosting site, we therefore asked teachers to supply estimates of thie information 2 weeks before the event.

6.4.4 Press

When possible, we worked with traditional and social media outlets to share information about the project and each SRS event. We sent a media advisory in the news cycle the week before the event (sample is accessible here) and published social media posts to our Facebook and Twitter accounts before, during, and after the event. We also encouarged all participating teachers and scientists to help spread the word about the project and the students’ successes via traditional and social media outlets.

6.4.5 Communication

With Event Staff: In the final week, we communicated final headcounts and any additional food restrictions with the caterer and location staff of the hosting facility.

With Educators: We sent the educators an email 2-3 weeks before the event with information about the event and requests for information about the student projects (see an example here). We followed up with an email a couple of days before the event with reminders and last minute updates (an example is here). We used a Google form to capture the key information that we needed from all of the educators prior to the event to best prepare ahead of time, this included things like:

- Headcount of students, educators, and other chaperones attending the event.

- Number of buses and cars attending.

- Titles of Investigations being reviewed by the scientists (as determined by the educators), with the student names from each group.

- Titles of Investigations being presented at the event but not reviewed by scientists (but reviewed by other educators and students at the event), with the student names from each group.

With Scientists: We sent out an initial request for participation about 6-12 weeks before the event (sample email can be accessed here). We sent this email to general list serves of scientists that may have been interested in participating (e.g., graduate student lists) as well as targeted emails to scientists involved in similar areas of the world or kinds of questions as the students had investigated. Once we had a line-up of participating scientists, then we also sent them an email communicating the logistics of the event (example can be accessed here). These emails detailed what the scientists could expect from the event, what we needed ahead of time from the scientists (i.e., photo of the scientist ideally doing data collection, tagline of what s/he loves about their job, and description of what s/he does), and a copy of the feedback form they would complete for their assisnted student groups at the event. Finally, we sent an email following the event to thank them for their participation and formally in a letter for their files (an example letter can be accessed here).

6.4.6 SRS Review Set-Up

Scientists each reviewed at least 4 group projects throughout the Student Poster Session. Additionally, students were reviewed by educators from other schools as well as their peers (educators did not review student groups from their own school). We developed a system for assigning reviewers before the event to ensure that all students received the same number of formal reviews.

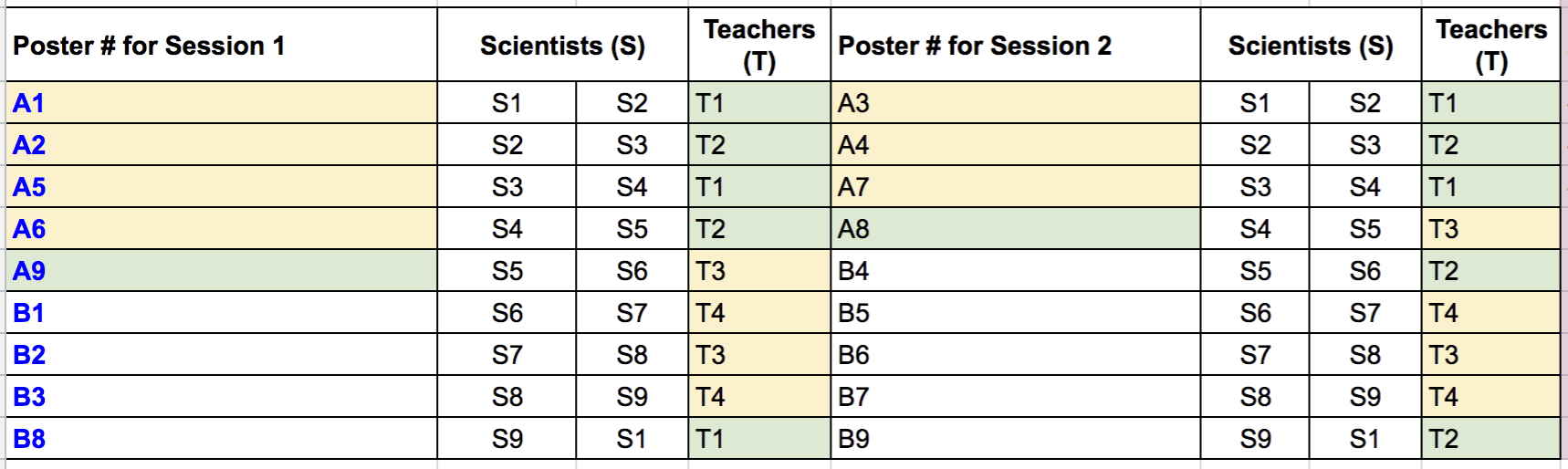

Each investigation project (aka poster name) received an alphanumeric code, A for investigations that would be reviewed by scientists and B for other investigations. Participating educators determined which student investigations they wanted to receive written feedback from participating scientists. The other student groups would receive written feedback from their peers and educators from other schools. Then each scientist received an alphanumeric code (S#) and finally each educator received an alphanumeric code (T#). We use these codes to help build the assignment matrix of investigation projects across scientists and teachers (Fig. 6). We always tried to mix up the investigation assignment groupings among the scientists, meaning that the scientists reviewed posters from different schools. A template for the Investigation Project Assignment Matrix that we use can be accessed here.

Figure 6. Example of matrix to assign student group posters to scientists and schools for review.

6.4.7 Materials for SRS Event

Below is a list of documents that we printed and distributed among the educators and the Sci-I Project team at the start of each SRS event (links to examples below):

- Participant schedule with map of poster layout across room

- Staff schedule with details of running the event

- “Script” to facilitate the event, we did not read this word-for-word but this helped us plan out what kinds of things we wanted to say throughout the event.

- Sign in sheets for schools as well as other participating adults (e.g., parents, press)

- Trackers of photo release forms (if required)

6.4.8 Post Event Logistics

Following the event we sent a thank you email to all of the participating educators. Additionally, we sent scanned copies of the completed feedback forms for each student group at their school so that the teachers could share them with their students (an example can be accessed here). We tried to send these emails within 48 hours of the event so that students received their written feedback as quickly as possible. We shared the scanned the forms rather than the originals for two reasons:

- we did not have time, or man power, during the event to gather and organize all of the completed forms by group and school to hand the forms to the educators as they left the event,

- we wanted the students to be able to see their feedback as quickly as possible and thus wanted to send them electronically rather than through the mail, and

- this way we had a copy of each completed feedback form if we wanted to look at them through the evaluation efforts of the program.

6.5 Event description

6.5.1 Set-Up

We have found it helpful to label the locations with the assigned poster alphanumeric codes both on the map and on the tables for students to more easily know where to setup their posters. Upon arrival, students set up their tri-fold posters on the table and attach the corresponding poster alphanumeric code label to a top corner of their posters with a binder clip. We found this approach helps reviewers and students locate the poster and if the title of the poster has changed since the educators completed the pre-SRS Google form (which often happens) the scientists were still able to find their assigned poster number.

6.5.2 During the Event

Upon arrival, we had all of the adults in each school group put on name tags and oriented the educators to the room set up. We invited the students to choose seats and stow their personal items under their seats. Then the students had time to set up their posters, as described above.

We kicked off the event with introductions made by the Sci-I Project staff, educators, and scientists. Each educator was asked to share how many students overall had participated in the project, and how many were attending the event. This helped provide the other schools and scientists a perspective on the size of the project. We asked each scientist to introduce themselves and explain in a few sentences who they were and what they did. As the room was often large, and thus it was often hard to see everyone when they were talking we also projected images of each scientist while they were introducing themselves (A sample slide deck from the 2017 New Jersey SRS can be accessed here).

We spent the remainder of the morning in the Student Poster Session. We found that two 30-minute sections to the session worked best for enabling students time to present their work while also managing the attention span of those not presenting. We divided the student groups in half. During Part I, one half of the student groups stood by their posters and presented their findings while the other half of the students completed feedback forms for their peers. At the end of 30 minutes, we gathered everyones attention and had the student groups rotate. We brought multiple copies of blank feedback forms (often a different color than those provided to the scientists), pens/pencils, and box to collect the completed forms so that non-presenting students had many opportunities to provide feedback to their peers.

Following the Poster Session, we would take our lunch break. After lunch, we facilitated a guided reflection on the Poster Session with the students (e.g., who had fun? Who was really nervous? Who thought it was easier than you expected?) and helped to facilitate the Scientist Panel. We found that 5-7 was a good number of scientists to participate in the panel (12 was way too many as not many students were able to ask questions with so many scientists responding, and 3 provided too narrow of a perspective for the students). We kicked off the panel with the scientists briefly introducing themselves and a prepared starting question for the scientists. Then we moderated the panel by having students ask questions of the scientists into the handheld microphones. Depending on the question, we would direct the question an individual scientist, a subset of the scientists, or all of the scientists on the panel to answer the question.

Before the end of the SRS event, we made sure to extend our deep appreciation for all who made the Sci-I Project and the SRS event possible: the students, the educators, the scientists, and the funding agency. We then encouraged the students to come up and ask any final questions of the scientists before retrieving their posters and heading back to their schools. Each time we have run the event at least a handful of students have come forward to ask the scientists for their autographs :).

A write up of our facilitation notes from the 2017 New Jersey SRS event can be accessed here.