Chapter 6 Civil war and terrorism (Week 6)

6.1 Discussion questions

Keen (2012): Why do wars occur within states? Aside from rebels’ greed and grievances, what additional questions should be addressed to explain civil wars?

Abrahms (2008): Why terrorism? Are terrorists rational? Can terrorism be prevented?

Should every group have a state of its own? What can be done about civil wars?

Does terrorism work (in terms of advancing a group’s interest)?

‘Monumental’ ceasefire agreed with Tigray rebels in Ethiopian civil war - BBC News

Colombia: FARC recruitment of child soldiers boosted by pandemic

Is Africa’s problem with Islamist terrorism getting worse? | DW News

6.2 Why do we discuss the two together?

To be clear, civil war and terrorism should not be treated equally. A civil war refers to a war where the main participants are within the same state. Terrorism is the use or threatened use of violence against noncombatant targets by indiviudals or nonstate groups for political ends.

But there are some good reasons to study the two together.

- Use of violence for political ends by nonstate actors that face the same fundamental problem (collective action).

- Employ similar strategies (asymmetric warfare).

- Close empirical relationship. See for instance, Findley & Young 2012.

6.3 Civil war

Keen (2012) focus on rejecting Collier’s greed thesis. His main criticisms are:

- Shaky empirical foundation (e.g. lack of access to education as proxy for greed)

- Wrong conclusions/assertions about country size

- Overconfident in drafting up policy proposals

- Internal contradictions (high military spending predicts renewed conflict (signal renegation); but contradicts with feasibility argument)

Despite these limitations, the greed argument is still popular because it is: attractively simple and politically convenient.

6.4 Terrorism

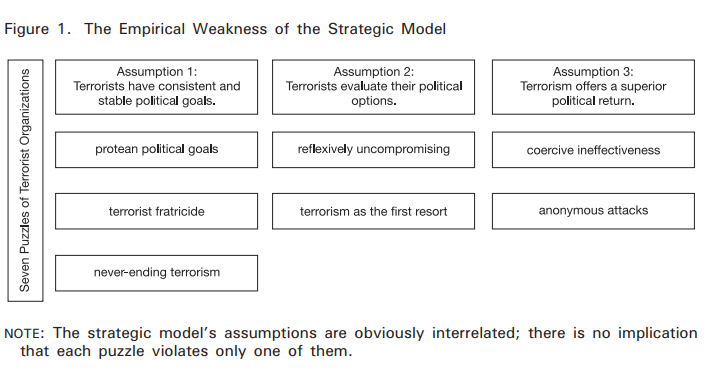

If the assumptions are flawed in the strategic model, then we are left with two possibilities: irrationality or terrorists join not for political return. Applying organization theory, Abrahms (2008) argues that terrorists join for the sense of solidarity. The theory suggests that “terrorist organizations will routinely engage in actions to perpetuate and justify their existence” (p.101). Indeed, terrorist organizations

- prolong their existence by relying on a strategy that hardens target governments from making policy concessions;

- ensure their continued viability by resisting opportunities to peacefully participate in the democratic process;

- avoid disbanding by reflexively rejecting negotiated settlements that offer significant policy concessions;

- guarantee their survival by espousing a litany of protean political goals that can never be fully satisfied;

- avert organization-threatening reprisals by conducting anonymous attacks, even though they preclude the possibility of coercing policy concessions;

- annihilate ideologically identical terrorist organizations that compete for members, despite the adverse effect on their stated political cause; and

- refuse to split up after the armed struggle has proven politically unsuccessful for decades or its political rationale has become moot.

Buying into this theory, how should we treat the current counterterrorism strategies: strict no concession, political accommodation, and democracy promotion. If terrorists are social solidarity maximizers, what strategies should governments take instead?

6.5 Resources

Terrorism by Our World in Data

Why Ethiopia is in a civil war

Five Years After Peace Deal, Colombia Is Running Out of Time, Experts Say

Why Russia Should Fear Being Declared A State Sponsor Of Terrorism

How Congress Should Designate Russia a State Sponsor of Terrorism

Opinion | A Dangerous Idea to Punish Putin

Russia Should Not be Designated a State Sponsor of Terrorism

Terrorism by Our World in Data

33 maps that explain terrorism

Colombia: U.S. Aids Peace by Lifting ‘Terrorist’ Label From FARC