5 Meta-regression

5.1 A brief introduction to mixed-effect meta-regression models

If you have seen meta-analyses in scientific articles, you’ve likely already come across meta-regression since they are a great way of summarizing key results from a meta-analysis–especially from heterogeneous datasets.

Fortunately, meta-regression builds right from the material we’ve covered in previous chapters. To perform a meta-regression, we have to identifying potentially moderating variables (could be discrete or continuous) that explain some of the variation we see in the overall datasets (S. Nakagawa et al. 2017). And there’s definitely an argument to be made that ecological meta-analysis should almost always incorporate some form of meta-regression since ecological data tend to be complex, with many potential moderating variables (Shinichi Nakagawa and Santos 2012).

5.2 Examples of meta-regression in ecological research

5.2.1 Meta-regression with microplastics

One ecology study that involved a meta-regression used some of the exact same R packages and statistical steps we’ll use in this chapter (Salerno et al. 2021). In their work, they explored the impact of microplastics on a number of fish traits (for example growth and survival).

Figure 5.1: Image of plastic bag and fish in the ocean

Their overall meta-analysis found a general decrease across the many traits that they collected data on as part of their study. And when they conducted a meta-regression, they wanted to determine whether the impacts on functional traits were more pronounced at different larval lengths (a continuous variable, measured in millimeters). They found that effect sizes were more negative (i.e., more negative values for their effect size, Hedges’ g) for greater sized larvae. So, in general, the impacts of microplastics on fish larvae depends on their size.

5.2.2 Meta-regression with forest thinning

We can look at another example of how some researchers explored the potential for the practices of forest thinning to reduce potential drought stress for some locations (Sohn, Saha, and Bauhus 2016). For a little background information, removing a select number of trees in some forests is thought to be a short-term solution to prevent mass tree die offs from drought conditions.

Figure 5.2: Image of ground cracking due to drought. Photo credit: Jorge Barrios

The authors of this study categorized the effect sizes from their overall meta-analysis into two sub-categories: effect sizes that come from either “moderately” or “heavily” thinned forest stands. What they found was that only in the heavily thinned plots did trees live longer and avoid declines due to both drought and tree age. So while the authors found that overall tree thinning did help the remaining stands of trees weather the drought period, the amount of thinning also plays a role in survival for the remaining trees.

5.3 Sample size and meta-regression

Before we dive into a meta-regression example, we need to discuss one more question that comes up for any statistical test–how do we know we have a large enough sample size to carry out a particular test? In the context of meta-regression, we need to make sure that the sample size of each moderating group meets a certain threshold for inclusion in our regression.

There is some disagreement in the literature about the lowest possible sample size (i.e., number of effect sizes) a sub-group can have for inclusion into meta-regression. Some studies include a sub-group in a meta-regression with as few as 3 effect sizes (Ferreira et al. 2016) others set the lower threshold as 10 effect sizes (Blouin et al. 2019). In my experience, I tend to take the average of this range and include sub-categories with 7 or more effect sizes [Crystal-Ornelas2021-sg].

5.4 Meta-regression with categorical variable

As usual, we’ll load the metafor package as well as some other packages that will help us with plotting

library(metafor)

library(DT)Note: the code below will not run unless you have run previous chapters of this book and/or you have RR_effect_sizes in your R environment (look for it in the environment tab of the top right panel if you are using Rstudio). Please re-run the R code that is in chapters 1 and 2 of this book if the dataframe isn’t there.

Our first meta-regression will be one that uses a categorical variable as a moderator. As a reminder, we have our example dataset with 88 effect sizes of invasive tree impacts on species richness.

Let’s take a look a look at the first 10 columns of our dataframe which contains all the effect sizes as well as many other columns of information such as the article’s first author (lastname), taxonomic group (invasive_species_taxonomic_group), and whether the study took place on an island or continent (island_or_continent).

datatable(RR_effect_sizes, fillContainer = TRUE)We’ll take a closer look at the categorical variable (island_or_continent) since we have good reason to believe that differences in impacts to biodiversity on islands may differ from mainland impacts. First, we’ll double check that we have at least 7 effect sizes in both sub-groups.

plyr::count(RR_effect_sizes$island_or_continent)## x freq

## 1 continent 73

## 2 island 15As you can see above, we have 73 effect sizes calculated for continents and 15 for islands, both of which are meet our threshold of 7 effect sizes.

5.4.1 Creating a model

Next, create the mixed effects model using the rma.mv function in the metafor package. Using this function, you’ll see how we can easily specify many different “arguments” or “parameters” of the model. We specify several arguments in this metafor model run. I explain each of the selections for the different arguments that are part of the rma.mv function in the code chunk below. That being said there are many different possible ways to create your models, so please read the metafor documentation to see what else you can do with this powerful function.

mix_effect_island_or_continent <-

rma.mv(

yi, # this is the column from our dataframe that contains calculated effect sizes

vi, # calculated variances

mods = ~ island_or_continent - 1, # Specify which moderators the model should take into account

random = ~ 1 | unique_article_identifier,

method = "REML", #Model fitting method

digits = 4, # round calculations to 4 digits

data = RR_effect_sizes

)## Warning: Rows with NAs omitted from model fitting.Earlier, I mentioned that this is a mixed effects model and looking at the code above, we can explore why this is called a mixed-effects model: within one model we account both for the fixed effect that we specify which is `island_or_continent’ as well as the random effect that comes from multiple effects sizes that were extracted from the same study. This mixed effects model is one way that we can account for the type of pseudoreplication that is common to meta-analytic datasets, when a single study contributes more that one effect size to a dataset.

To see the output of our meta-regression model we just run the object called mix_effect_island_or_continent that we created in the previous code chunk:

mix_effect_island_or_continent##

## Multivariate Meta-Analysis Model (k = 84; method: REML)

##

## Variance Components:

##

## estim sqrt nlvls fixed factor

## sigma^2 0.1581 0.3976 59 no unique_article_identifier

##

## Test for Residual Heterogeneity:

## QE(df = 82) = 1029.9538, p-val < .0001

##

## Test of Moderators (coefficients 1:2):

## QM(df = 2) = 18.4496, p-val < .0001

##

## Model Results:

##

## estimate se zval pval ci.lb ci.ub

## island_or_continentcontinent -0.2679 0.0637 -4.2049 <.0001 -0.3927 -0.1430 ***

## island_or_continentisland -0.1133 0.1293 -0.8764 0.3808 -0.3668 0.1401

##

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 15.4.2 Presenting results

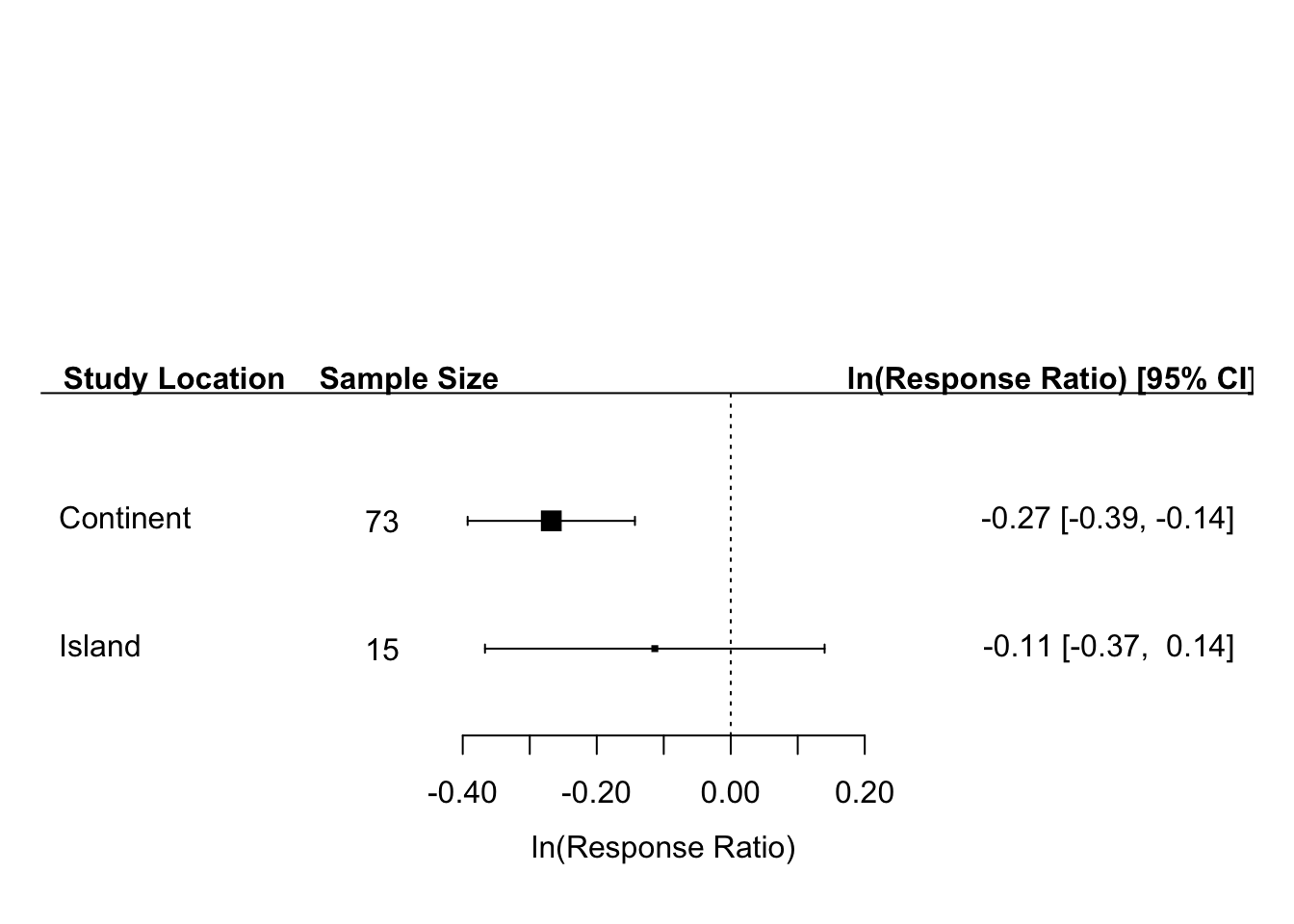

In the very first column we see the names of the two subcategories “continent” and “island” (they are appended to the variable name island_or_continent).

Looking at the continent row, we see an effect size of -0.2679. Which indicates a negative impact of invasive trees on species richness. However, we need to check whether the p-value is below the threshold of 0.05 to determine if this negative impact is statistically significant. Our mixed effects model shows the the p-value for this sub-category is 3^{-5}–well below the threshold. So in summary, invasive trees on mainlands have significantly negative impacts on species richness. While it’s important to know that the negative impact is significant, the Log of the Response Ratio (i.e., the ln(RR)) estimate is sometimes not the easiest to interpret. Fortunately, there’s a simple conversion from the ln(RR) to percent increase or decrease (depending on the sign of the effect). It’s \[ PercentageIncreaseOrDecrease = 100 * (e^{ln(RR)}-1)\]. So when we plug in our effect size estimate of -0.2679 to this equation we get a decrease in richness of -23.498 when invasive species are present compared to locations without invasive trees.

Previous findings suggests impacts of plants don’t differ between island and mainland (Vilà et al. 2011).

5.4.3 Making a figure

After looking at the statistical output of the meta-regression, it’s time to create our data visualization. The typical visualizations for meta-regression are not that different from what we’ve already seen as the forest plots for overall meta-analyses, with meta-regressions we will provide summary statistics for the two sub-groups as part of the forest plot.

First, let’s just confirm the number of effect sizes in each sub-group

plyr::count(RR_effect_sizes$island_or_continent)## x freq

## 1 continent 73

## 2 island 15Then, save the sample size in each category as an object. As you’ll see later, this step is important for plotting sample size numbers as part of our visualization.

continent_and_island_sample_size <- c(73,15)Then we can make our forest plot using the forest function in the metafor package. As with the meta-regression model, there’s so much we can customize in these forest plot diagram. See my comments in the code below to see how I use each argument to customize the plot.

forest_plot_continent_and_island <- forest(mix_effect_island_or_continent$b, # This is our vector of two effect sizes for our 2 sub-categories

ci.lb = mix_effect_island_or_continent$ci.lb, # Confidence interval lower bounds

ci.ub = mix_effect_island_or_continent$ci.ub, # Confidence interval upper bounds

annotate = TRUE, # This tells function to list effect size and CIs for each group on our graph

xlab = "ln(Response Ratio)", # label for x-axis

slab = c("Continent", "Island"), #label for y-axis

cex = 1, # Font size for entire graph (excluding headers)

digits = 2 # Round effect size and CI to 2 digits

)

# Then, you have to add a bit more code to get the correct labels to appear on the graph

text(-.52, rev(seq(2:1)), continent_and_island_sample_size, cex = 1) # Code to write sample size of sub-groups on graph

op <- par(cex=1, font=2) # Set up font for rest of graph (just the headers of the graph remain), to make bold headings, set font=2

text(-.83, 3.1, "Study Location") # For this code, enter x-position of text, then y-position. You may have to experiment a bit.

text(-.48, 3.1, "Sample Size")

text(.48, 3.1, "ln(Response Ratio) [95% CI]")

Our forest plot helps to convey, in one concise data visualization all the results of our meta-regression. On the left of our plot, we see the two levels of our categorical variable (continent and island) as well as their respective sample sizes. Then we see the horizontal box and whisker plots typical of meta-analysis. The small square box for each sub-group indicates the average effect size for that group and the whiskers are the associated confidence intervals. As with all previous forest plots, because the confidence interval for the Island subgroup crosses the vertical dotted line, the average effect size for the island subgroup is not significant. On the right side of the plot we also provide the effect size and CI in numerical form in case readers would like to see the actual numbers rather than the box and whisker plot.

5.5 Meta-regression with continuous variable

Sometimes the moderating variable you want to include in a meta-regression is continuous rather than categorical. The initial steps to create this type of meta-analysis are quite similar to the categorical meta-analysis steps, however, the functions you use to create the model and plots will be new for us.

5.5.1 Example of meta-regression with continuous variable

One of the continuous variables we include in our original database is the variable time_since_invasion. Time since invasion is in important concept in invasion science, since the longer duration a novel species exists in a new location, the greater the potential impact it may have on the ecosystem. Some meta-analysts have already taken to investigating this question through data synthesis, so let’s take a quick look at their meta-analysis which aggregated data from studies taking place in greenhouses (Iacarella, Mankiewicz, and Ricciardi 2015).

Figure 5.3: Series of glass-walled greenhouses. Photo credit: Quistnix

In their study, the authors brought together data from 26 articles that measured competition between native and invasive plants. Even though the studies all took place in controlled greenhouse settings, they could determine the number of years that the original collection site had been invaded. Ultimately, they found that competition between invasive and native plants were actually strongest in the earlier years of invasion while over time the competitive effects weakened. They took their meta-regression a step further and found that changes in impact magnitude over time decreased more sharply for grasses compared to other plant groups in their meta-analysis.

5.5.2 Creating a model

Let’s create a meta-regression model to determine whether time since invasion time_since_invasion moderates invasive species impacts on biodiversity (measured as species richness yi in our database). To do so, we’ll use the R package lme4.

library(lme4)

library(ggplot2)

library(cowplot)Next, we can set up our meta-regression model. We’ll use a function from the lme4 package rather than a function from metafor. As you can see in the code below, the function lmer requires just a small number of inputs. Refer to the comments in the code chunk below to see what each component of the function does.

time_since_invasion_meta_reg <- lmer(yi ~ # Effect sizes

(1 | unique_article_identifier) + # Random effect is the study (to account for potential pseudoreplicaton)

time_since_invasion, # Fixed effect is time since invasion.

data = RR_effect_sizes) # The data frame that contains all the vectors of numbers we call in this function

summary(time_since_invasion_meta_reg) # This prints the results of our meta-regression## Linear mixed model fit by REML ['lmerMod']

## Formula: yi ~ (1 | unique_article_identifier) + time_since_invasion

## Data: RR_effect_sizes

##

## REML criterion at convergence: 78.6

##

## Scaled residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.71888 -0.28280 0.03127 0.25561 1.53308

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

## unique_article_identifier (Intercept) 0.1769 0.4205

## Residual 0.0960 0.3098

## Number of obs: 50, groups: unique_article_identifier, 33

##

## Fixed effects:

## Estimate Std. Error t value

## (Intercept) -0.119945 0.153787 -0.780

## time_since_invasion -0.001175 0.001066 -1.102

##

## Correlation of Fixed Effects:

## (Intr)

## tm_snc_nvsn -0.821There are many results to sort through, but we’ll focus on just a few here! First, note that in the results under “number of observations” we have dropped down from 88 effect sizes in our main dataset to only 50. This is because for some studies it was unclear how long the study site had been invaded, and so these effect sizes were removed from our model calculations. Later chapters will discuss the possibility of imputing these types of missing values.

The main results of a mixed effect model you may choose to highlight in a presentation or a publication are listed in the table below. One other output that is not provided by the summary function above, but that will be useful for our results table is confidence interval estimates. We can get those by running the following code.

confint(time_since_invasion_meta_reg)## Computing profile confidence intervals ...## 2.5 % 97.5 %

## .sig01 0.228525961 0.5780598546

## .sigma 0.228068886 0.4477882514

## (Intercept) -0.421331704 0.1806808375

## time_since_invasion -0.003257512 0.0009105184Onto the interpreting all of the meta-regression model results. They are often presented in a table like the one below, and can get more complex if more moderators are added to the mixed effects regression or even interactions between moderators (e.g., time_since_invasion * country).

5.5.3 Presenting results

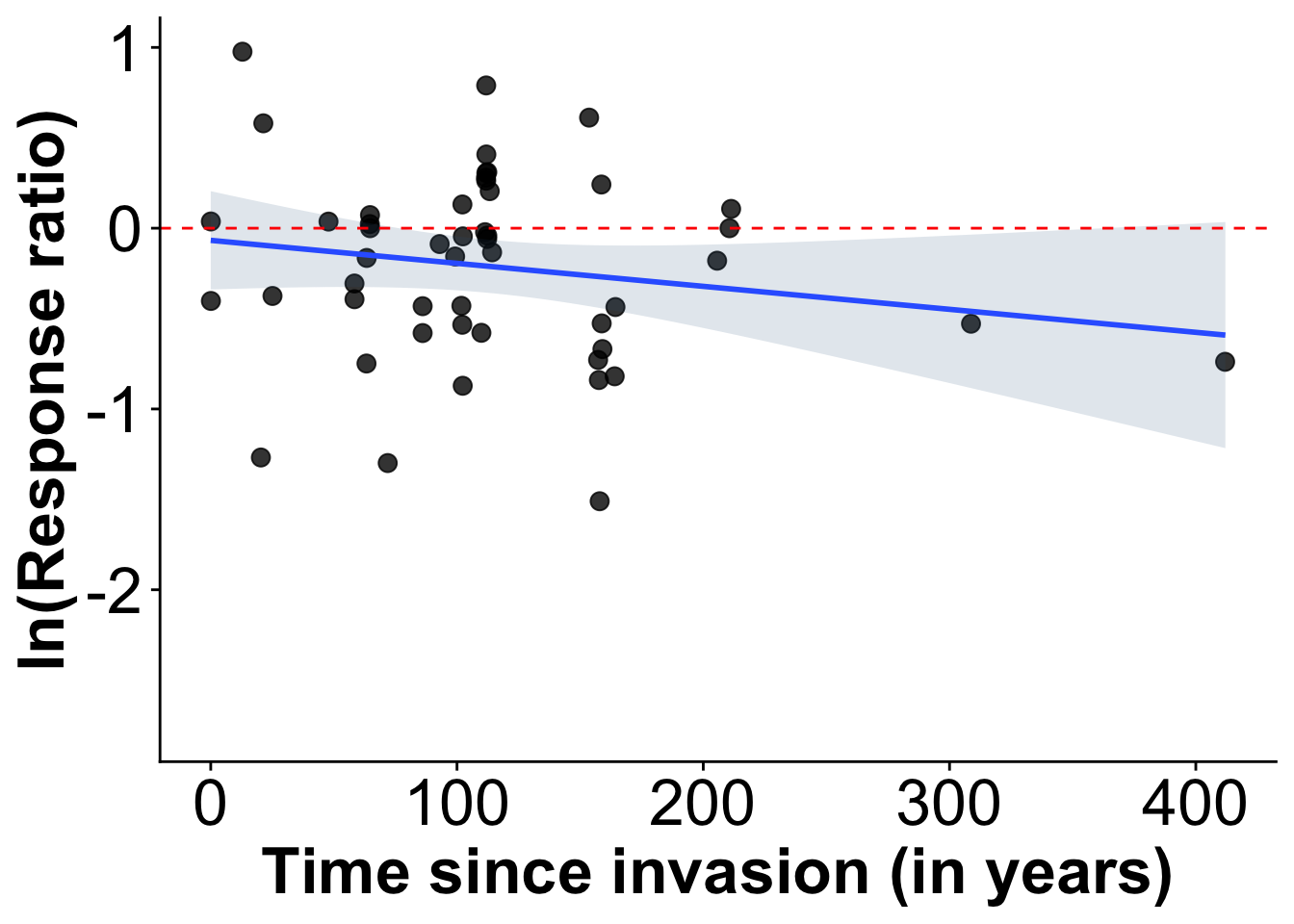

The first result we present in the table below is the model’s beta value or slope of the best fit line in this mixed effects meta-regression. We see that, unlike the greenhouse study we discussed above, the slope of our regression line is negative, meaning that as time since invasion increased, the effect sizes in our database become more negative. In other words, the longer the invasive tree had been in a location, the worse its effects on species richness. Though the magnitude of the effect is relatively weak (0.0012) this is typical of large heterogeneous ecological datasets like the one we are using. The confidence interval skews towards negative values, but includes 0, we can’t fully say with certainty that the overall negative decline is significant in our model. Lastly, the large standard deviation of the random effect means that there’s relatively high variation from one study to the next.

| Fixed effect | Beta | SE | Lower-95 | Upper-95 | Random Effect | RE SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| time since invasion | -0.0012 | 0.0011 | -0.0033 | 0.00091 | Study ID | 0.4205 |

5.5.4 Making a figure

While the table is helpful for concisely presenting results, visualizing all of this information in figure is common as well. The code from ggplot2 below plots all the available effects sizes by their time since invasion and magnitude, then fits a line to the points. I like to add in the horizontal red line to show the “line of no effect” and really emphasize when confidence intervals or effect sizes are close to or overlap zero.

time_since_invasion_plot <-

ggplot(data = RR_effect_sizes, # Bring in the dataframe containing effect sizes

aes(

x = time_since_invasion, # Plot time along x-axis

y = yi, # Effect sizes along y-axis

)) +

geom_point(size = 3, # Make points on plot relatively large

alpha = .8, # Make points on plot slightly transparent in case they overlap

position = "jitter") + # Jitter the points so they don't overlap

geom_smooth(

method = lm,

se = TRUE,

size = 1,

alpha = .15,

fill = "#33638DFF"

) +

theme_cowplot() + # I like this plot theme for it's simplicity

xlab("Time since invasion (in years)") + # Label the axes

ylab("ln(Response ratio)") +

geom_hline(yintercept=0, linetype="dashed", color = "red", size =0.5) + # add in horizontal red line to show "line of no effect"

theme( # More theme customizations so that the plot is ready to present in a paper/presentation.

axis.title = element_text(size = 25, face = "bold"),

title = element_text(size = 25, face = "bold"),

axis.text = element_text(size = 25),

legend.title = element_text(size = 25),

legend.text = element_text(size = 25))

time_since_invasion_plot## `geom_smooth()` using formula 'y ~ x'## Warning: Removed 38 rows containing non-finite values (stat_smooth).## Warning: Removed 38 rows containing missing values (geom_point). As you can see in the plot above, at the very earliest years after invasion effect sizes were not significantly different from zero. This indicates that, on average, invasive species did not have significant impacts on richness immediately. However, in the middle time ranges (e.g., 100-300 years) the confidence interval (gray shading) fully dips below the red line indicating a significant decline in richness. Then as we move further along the x-axis though the remaining few point suggest large negative impacts, the data points are limited and variable, so the confidence interval flares out again.

As you can see in the plot above, at the very earliest years after invasion effect sizes were not significantly different from zero. This indicates that, on average, invasive species did not have significant impacts on richness immediately. However, in the middle time ranges (e.g., 100-300 years) the confidence interval (gray shading) fully dips below the red line indicating a significant decline in richness. Then as we move further along the x-axis though the remaining few point suggest large negative impacts, the data points are limited and variable, so the confidence interval flares out again.