1 Object Relational Calculus

1.1 Introduction

A database, data store, object store, or knowledge base is simply a collection of information objects. The objects have structure and properties and are often related. The format in which the objects are represented might differ. For example, in a relational database, the objects are organized into tables while in an XML store, the objects are elements delimited by tags. However, their essence is quite the same: a collection of information objects — or simply, objects.

For example, a datastore might contain information on assets and their owners. So, the datastore is a collection of individual asset objects and owner objects with associations that indicate which assets belongs to which owner. Each object is by itself some structural arrangement of data values called the object’s attributes or data properties. Every asset object might have attributes such as name, acquisition cost, acquisition date, vendor, and depreciation time. In order to distinguish different assets, each asset object must have a unique identifier — its primary key or object ID.

An object store.

The calculus described in this chapter is a modernization of the tuple relational calculus originally created by Edgar F. Codd for the relation model.

A calculus is a method for reasoning. The object relational calculus is a method for reasoning about object stores and information retrieval from such stores.

There are many call that pertain to the relational mode, including the tuple relational calculus and the more recent domain relational calculus. Additionally, the relational algebra is a procedural abstraction of queries for relational databases.

1.2 Definition of an Object Store

This section defines the various elements of an object store using (somewhat) formal definitions with the intent of reducing ambiguity and eventually allowing a language independent specification of information retrieval from a store.

Definition: Class

A class \(C\) is a set of object \(o_1\), \(o_2\), \(o_3\), …, \(o_n\), i.e., \(C=\{o_1, o_2, o_3, ..., o_n\}\) that have the same properties. All objects with the same properties must be members of the same class. \(C\) be the set of objects \(o_1\), \(o_2\), \(o_3\), …, \(o_n\), i.e., \(C=\{o_1, o_2, o_3, ..., o_n\}\).

Definition: Object Store

An object store \(\mathfrak{S}\) is a collection of classes \(C_1, C_2, ..., C_n\) and relations \(R_1, R_2, ..., R_n\) between the members of the classes.

Definition: Object

An object is a single member of a class, i.e., an object \(o\) that belongs to class \(C\) is denoted either as \(o^C\) or \(o \in C\).

Definition: Instance

An instance is a specific unique object of a class and is denoted by specifying its unique object identifier and its class, e.g., \(o^C_{id}\).

Definition: Tuple

A tuple is a set of values, e.g., the tuple \(T\) is the set of values \((v_1, v_2, ..., v_n)\). Every object is a tuple. All objects in a class have the same tuple structure.

Definition: Object Identifier

Objects are distinguished by their identifier, \(o_{id}\) which means that if \(o_j \in C\) and \(o_k \in C\) and if \(j = k\), then \(o_j = o_k\).

Definition: Domain

A domain \(D\) is the set of values from which a value for an attribute is drawn. A domain can be any infinite set such as \(\mathbb{R}\) or \(\mathbb{Z}\) or a finite set such as \(\{T, F\}\).

Definition: Attribute

An object is a tuple of attributes \((a_1, a_2, ..., a_n)\) defining its structure. Each attribute \(o.a_i\) (also known as data property, feature, or dimension) takes on one value at a time from a single domain. In other words, if \(o_p\) and \(o_q\) are two objects such that \(p\neq q\), then for any attribute \(a_i\), its values must be drawn from the same domain \(D\), i.e., if \(o_p.a_i \in D\), then \(o_q.a_i \in D\).

Definition: Cardinality

The cardinality of a class \(C\) is the number of objects in the class and is denoted as \(|C|\).

Definition: Relation

A relation \(R\) is a non-injective function \(f\) that maps objects from one class \(C_i\) to another class \(C_j\), i.e., \(f = R : C_i \to C_j\) where \(C_i,C_j \in \mathfrak{S}\). Since \(i\) can equal \(j\), relations can be reflexive.

Definition: Multiplicity

The multiplicity of a relation \(R\) is the .

Definition: Object Equality

The

Definition: Object Equivalence

The m

1.3 Retrieval Specification

A retrieval from an object store is a logical expression that defines through boolean expressions which objects are part of the result set. A results set is an anonymous class of tuples, or simply tuples.

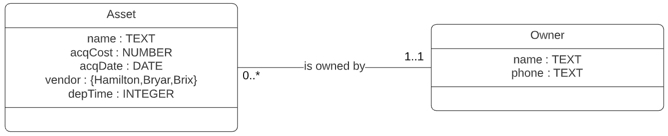

Let us assume that we have an object store \(\mathfrak{S}\) with classes Asset (\(A\)) and Owner (\(O\)). Furthermore, let us assume that the classes have the following structure in terms of attribute and their domains:

class Asset {

name : TEXT;

acqCost : {v : v > 0}

acqDate : DATE;

vendor : {Hamilton,Bryar,Brix};

depTime : {1, 5, 7, 20}

} class Owner {

dep : TEXT;

phone : TEXT;

} In addition to the above defined attributes for each class, there is an implied object identifier (primary key). It does not have to be explicitly stated. Neither do foreign keys that implement the relationship between Asset and Owner. Let us assume that every asset is owned by exactly one owner. This implies that an asset must have an owner, although some owners may not own any assets. The figure below shows a UML visualization of the ontology.

Figure 1. UML Diagram for Asset Ownership Ontology

The diagram above shows that an Asset is owned by exactly one owner and that an Owner can own several assets. The relationship between the two classes represents the Ownership relation.

1.3.1 General Form

The general format of a retrieval specification (query in database terms) is a set definition. The result of a retrieval is a set. This set is often called the \(result set\), or \(rs\).

\(rs=\{x : cond(x)\}\)

where \(cond(x)\) is a boolean expression2.

For example, to retrieve all owners from the object store \(\mathfrak{S}\), the following set definition specifies the boolean expressions resulting in the desired result set:

\(rs=\{x : x\in Owner\}\)

1.3.2 Restrictions

Restrictions are expressed as additional boolean expressions. For example, all assets with an acquisition cost of more than $1,000 and a depreciation time of less than 7 years would be expressed with this set definition:

\(rs=\{x : (x\in Asset)\land(x.acqCost \gt 1000)\land(x.depTime \lt 7)\}\)

The set is restricted to all objects that satisfy all conditions, i.e., all objects for which all boolean expressions evaluate true.

Note that if the expression \(x\in Asset\) were missing then \(x\) would not be bound to the elements in the Asset class; it would specify all objects from all classes in the object store \(\mathfrak{S}\). This would lead to specification problems as the attributes in the definition would not be necessarily defined for all classes and their domains might differ. For example, two classes might have a name attribute but for one it might be drawn from the TEXT domain while for another it might be drawn from the INTEGER domain.

Restrictions are similar to predicate expressions in XPath or the WHERE clause in SQL.

1.3.3 Selections

Selecting specific attributes instead of entire objects can be done with tuple specifications. Below is an example where the result set consists of tuples that contain only the name and acqDate attributes of the specified objects:

\(rs=\{x.name, x.acqDate : (x\in Asset)\land(x.acqCost \gt 1000)\}\)

1.3.4 Existential Quantification

An existential quantifier (\(\exists\)) is a special boolean expression that is true if the specified conditions is true for at least some (at least one) objects.

1.3.5 Universal Quantification

A universal quantifier (\(\forall\))is a boolean expression that defines a condition that is true for all objects.

1.3.6 Joins

A join retrieval specification selects result set tuples where conditions are

1.4 Notes on Mathematical Notation

The lecture notes use several notational devices from set theory and Boolean logic that may not be familiar to everyone.

1.4.1 Set Notation

A set of simply a collection of elements. For example, a book is a collection of pages. Elements must be unique, so a set cannot contain the same element more than once. Often sets are denoted with a capital letter, e.g., \(Q\). Set membership is indicated with the symbol \(\in\).

Sets can be described in several ways:

By listing the elements:

\(HockeyBag = \{skates, elbow pads, helmet, kneepads, gloves\}\)By suggesting a pattern:

\(evenNums=\{2, 4, 6, ..., 100\}\)Using set builder notation:

\(evenNums=\{x\in {\mathbb{Z}} : 1 \leq x \leq 100 \space \wedge \space x\mod 2=0\}\)

Common pre-defined sets cover numeric sets:

| Symbol | Set | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| \(\mathbb{R}\) | real numbers | 9.1, -0.08, \(\pi\) |

| \(\mathbb{Z}\) | integers (whole numbers) | -10, 0, 8 |

| \(\mathbb{Q}\) | rational numbers (fractions) | 9.1 (\(9\frac{1}{10})\) |

| \(\mathbb{N}\) | natural numbers (integers \(>\) 0) | 0, 3, 61 |

Each of the above sets can be restricted to just positive number by including a \(+\) superscript, e.g., \(\mathbb{R}^+\).

1.4.2 Boolean Logic Notation

Boolean logic defines expressions that are either \(True\) or \(False\).

| Symbol | Meaning | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| \(\land\) | \(AND\); only \(TRUE\) when both expressions are true | \((x<10) \wedge (x \mod 3=0)\) |

| \(\lor\) | \(OR\); \(TRUE\) when either expression is true | \((x<10) \lor (x \mod 3=0)\) |

1.5 Exercises

1.5.1 Exercise 1

Create retrieval specifications for the object store \(\mathfrak{S}\) from this chapter:

- Find all assets that are sold by either “Bryar” or “Brix”.

- Find all assets that are owned by “Chris Topher”.

- Find all assets that are owned by “Chris Topher” that cost more than $1,000.

1.5.2 Exercise 2

Assuming that Asset \(\in \mathfrak{S}\), express the retrieval specification for \(rs\) in XPath and in SQL.

\(rs=\{x : (x\in Asset)\land(x.acqCost \gt 1000)\land(x.depTime \lt 7)\}\)

What assumptions do you need to make about the relations in the relational database or the element structure in the XML store?

A vertical bar is also often used in lieu of the colon to express a set using the set construction syntax, e.g., \(rs=\{x | cond(x)\}\)↩