Chapter 17 Most Powerful Tests, Size of Union-Intersection and Intersection-Union Tests, p-Values(Lecture on 02/20/2020)

Example 17.1 (UMP Binomial Test) Let \(X\sim Bin(2,\theta)\). We want to test \(H_0:\theta=\frac{1}{2}\) versus \(H_1:\theta=\frac{3}{4}\). Calculating the ratios of the p.m.f. gives \[\begin{equation} \frac{f(0|\theta=\frac{3}{4})}{f(0|\theta=\frac{1}{2})}=\frac{1}{4} \quad \frac{f(1|\theta=\frac{3}{4})}{f(1|\theta=\frac{1}{2})}=\frac{3}{4} \quad \frac{f(2|\theta=\frac{3}{4})}{f(2|\theta=\frac{1}{2})}=\frac{9}{4} \tag{17.1} \end{equation}\] If we choose \(\frac{3}{4}<k<\frac{9}{4}\), the Neyman-Perason Lemma says that the test that rejects \(H_0\) if \(X=2\) is the UMP level \(\alpha=P(X=2|\theta=\frac{1}{2})=\frac{1}{4}\) test. If we choose \(\frac{1}{4}<k<\frac{3}{4}\), the Neyman-Perason Lemma says that the test that rejects \(H_0\) if \(X=1\) or 2 is the UMP level \(\alpha=P(X=1\,or\,2|\theta=\frac{1}{2})=\frac{3}{4}\) test. Choosing \(k<\frac{1}{4}\) or \(k>\frac{9}{4}\) yields the UMP level \(\alpha=1\) or level \(\alpha=0\) test.

Note that if \(k=\frac{3}{4}\), then (16.11) says we must reject \(H_0\) for the sample point \(x=2\) and accept \(H_0\) for \(x=0\) but leaves our action for \(x=1\) undetermined. If we accept \(H_0\) for \(x=1\), we get the UMP level \(\alpha=\frac{1}{4}\) test as above. If we reject \(H_0\) for \(x=1\), we get the UMP level \(\alpha=\frac{3}{4}\) test as above.Proof. Let \(\beta(\theta)=P_{\theta}(T>t_0)\) be the power function of the test. Fix \(\theta^{\prime}>\theta_0\) and consider testing \(H_0^{\prime}:\theta=\theta_0\) versus \(H_1^{\prime}:\theta=\theta^{\prime}\). Since the family of p.d.f. or p.m.f. of \(T\) has an MLR, \(\beta(\theta)\) is nondecreasing, so

\(\sup_{\theta\leq\theta_0}\beta(\theta)=\beta(\theta_0)=\alpha\), and this is a level \(\alpha\) test.

- If we define \(k^{\prime}=\inf_{t\in\mathcal{T}}\frac{g(t|\theta^{\prime})}{g(t|\theta_0)}\), where \(\mathcal{T}=\{t:t>t_0,\,either\,g(t|\theta^{\prime})>0\,or\,g(t|\theta_0)>0)\}\), it follows that \[\begin{equation} T>t_0 \Leftrightarrow \frac{g(t|\theta^{\prime})}{g(t|\theta_0)}>k^{\prime} \tag{17.3} \end{equation}\] Together with Corollary 16.1, (i) and (ii) imply that \(\beta(\theta^{\prime})\geq\beta^*(\theta^{\prime})\), where \(\beta^*(\theta)\) is the power function for any other level \(\alpha\) test of \(H_0^{\prime}\), that is, any test satisfying \(\beta(\theta_0)\leq\alpha\). However, any level \(\alpha\) test of \(H_0\) satisfies \(\beta^*(\theta_0)\leq\sup_{\theta\in\Theta_0}\beta^*(\theta)\leq\alpha\). Thus, \(\beta(\theta^{\prime})\geq\beta^*(\theta^{\prime})\) for any level \(\alpha\) test of \(H_0\). Thus, \(\beta(\theta^{\prime})\geq \beta^*(\theta^{\prime})\) for any level \(\alpha\) test of \(H_0\). Since \(\theta^{\prime}\) was arbitrary, the test is a UMP level \(\alpha\) test.

By an analogous argument, it can be shown that under the conditions of Theorem 17.1, the test that rejects \(H_0:\theta\geq\theta_0\) in favor of \(H_1:\theta<\theta_0\) if and only if \(T<t_0\) is a UMP level \(\alpha=P_{\theta_0}(T<t_0)\) test.

Example 17.3 Consider testing \(H_0^{\prime}:\theta\geq\theta_0\) versus \(H_1^{\prime}:\theta<\theta_0\) using the test that rejects \(H_0^{\prime}\) if \(\bar{X}<-\frac{\sigma z_{\alpha}}{\sqrt{n}}+\theta_0\). As \(\bar{X}\) is sufficient and its distribution has an MLR, it follows from Theorem 17.1 that the test is a UMP level \(\alpha\) test in this problem.

As the power function of this test, \[\begin{equation} \beta(\theta)=P_{\theta}(\bar{X}<-\frac{\sigma z_{\alpha}}{\sqrt{n}}+\theta_0) \tag{17.4} \end{equation}\] is a decreasing function of \(\theta\) (since \(\theta\) is a location parameter in the distribution of \(\bar{X}\)), the value of \(\alpha\) is given by \(\sup_{\theta\geq\theta_0}\beta(\theta)=\beta(\theta_0)=\alpha\).Example 17.4 (Nonexistence of UMP Test) Let \(X_1,\cdots,X_n\) be i.i.d. \(N(\theta,\sigma^2)\), \(\sigma^2\) known. Consider testing \(H_0:\theta=\theta_0\) versus \(H_1:\theta\neq\theta_0\). For a specified value \(\alpha\), a level \(\alpha\) test in this problem is any test that satisfies \[\begin{equation} P_{\theta_0}(reject\,H_0)\leq \alpha \tag{17.5} \end{equation}\] Consider an alternative parameter point \(\theta_1<\theta_0\). Tha analysis in Example 17.3 shows that, among all tests that satisfy (17.5), the test that rejects \(H_0\) if \(\bar{X}<-\frac{\sigma z_{\alpha}}{\sqrt{n}}+\theta_0\) has the highest possible power at \(\theta_1\). Call this Test 1. Furthermore, by necessity of the Neyman-Pearson Lemma, any other level \(\alpha\) test that has as high a power as Test 1 at \(\theta_1\) must have the same rejection region as Test 1 except possibly for a set \(A\) satisfying \(\int_{A}f(\mathbf{x}|\theta_i)d\mathbf{x}=0\). Thus, if a UMP level \(\alpha\) test exists for this problem, it must be Test 1 because no other test has as high a power as Test 1 at \(\theta_1\).

Now consider Test 2, which rejects \(H_0\) if \(\bar{X}>\frac{\sigma z_{\alpha}}{\sqrt{n}}+\theta_0\). Test 2 is also a level \(\alpha\) test. Let \(\beta_i(\theta)\) denote the power function of Test \(i\), for any \(\theta_2>\theta_0\), \[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \beta_2(\theta_2)&=P_{\theta_2}(\bar{X}>\frac{\sigma z_{\alpha}}{\sqrt{n}}+\theta_0)\\ &=P_{\theta_2}(\frac{\bar{X}-\theta_2}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}}> z_{\alpha}+\frac{\theta_0-\theta_2}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}})\\ &>P(Z>z_{\alpha})=P(Z<-z_{alpha})\\ &>P_{\theta_2}(\frac{\bar{X}-\theta_2}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}}< -z_{\alpha}+\frac{\theta_0-\theta_2}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}})\\ &=P_{\theta_2}(\bar{X}<-\frac{\sigma z_{\alpha}}{\sqrt{n}}+\theta_0)\\ &=\beta_1(\theta_2) \end{split} \tag{17.6} \end{equation}\]

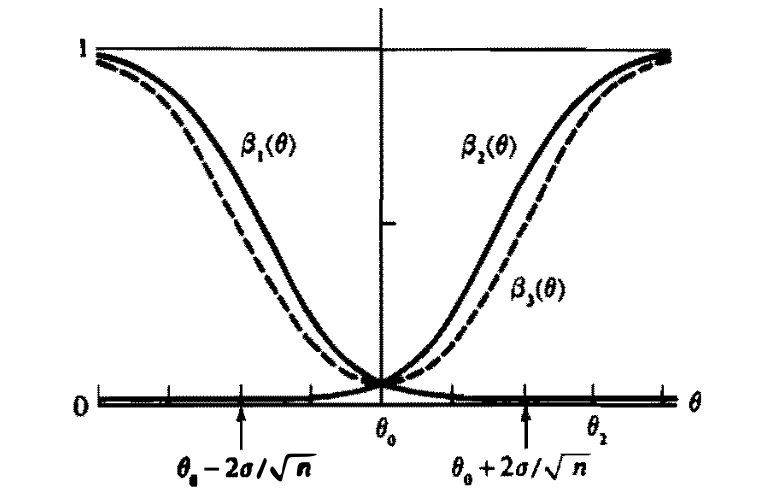

Thus, Test 1 is not a UMP level \(\alpha\) test because Test 2 has a higher power than Test 1 at \(\theta_2\). Earlier we showed that if there were a UMP level \(\alpha\) test, it would have to be Test 1. Therefore, no UMP level \(\alpha\) test exists in this problem.Example 17.5 (Unbiased Test) When no UMP level \(\alpha\) test exists within the class of all tests, we might try to find a UMP level \(\alpha\) test within the class of unbiased tests. The power function \(\beta_3(\theta)\) of Test 3, whihc rejects \(H_0:\theta=\theta_0\) in favor of \(H_1:\theta\neq\theta_0\) if and only if \(\bar{X}>\frac{\sigma z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}+\theta_0\) or \(\bar{X}<-\frac{\sigma z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}+\theta_0\) as well as \(\beta_1(\theta)\) and \(\beta_2(\theta)\) in Example 17.4 is shown in Figure 17.1. Test 3 is actually a UMP unbiased level \(\alpha\) test.

Note that although Test 1 and Test 2 have slightly higher powers than Test 3 for some parameter points, Test 3 has much higher power than Test 1 and Test 2 at other parameter points. For example, \(\beta_3(\theta_2)\) is near 1, whereas \(\beta_1(\theta_2)\) is near O. If the interest is in rejecting \(H_0\) for both large and small values of 0, Figure 17.1 shows that Test 3 is better overall than either Test 1 or Test 2.

FIGURE 17.1: Power functions for three tests

Because of the simple way in which they are constructed, the sizes of union-intersection tests (UIT) and intersection union tests (IUT) can often be bounded above by the sizes of some other tests. Such bounds are useful if a level \(\alpha\) test is wanted, but the size of the UIT or IUT is too difficult to evaluate.

Let \(\lambda_{\gamma}(\mathbf{x})\) be the LRT statistic for testing \(H_{0_{\gamma}}:\theta\in\Theta_{\gamma}\) versus \(H_{1_{\gamma}}:\theta\in\Theta_{\gamma}^c\), and let \(\lambda(\mathbf{x})\) be the LRT statistic for testing \(H_0:\theta\in\Theta_0\) versus \(H_1:\theta\in\Theta_0^c\).

Theorem 17.2 Consider testing \(H_0:\theta\in\Theta_0\) versus \(H_1:\theta\in\Theta_0^c\), where \(\theta_0=\bigcap_{\gamma\in\Gamma}\Theta_{\gamma}\) and \(\lambda_{\gamma}(\mathbf{x})\) is defined as previous. Define \(T(\mathbf{x})=\inf_{\gamma\in\Gamma}\lambda_{\gamma}(\mathbf{x})\), and form the UIT with rejection region \(\{\mathbf{x}:\lambda_{\gamma}(\mathbf{x})<c,\gamma\in\Gamma\}=\{\mathbf{x}:T(\mathbf{x})<c\}\). Also consider the usual LRT with rejection region \(\{\mathbf{x}:\lambda(\mathbf{x})<c\}\). Then

\(T(\mathbf{x})\geq \lambda(\mathbf{x})\) for every \(\mathbf{x}\);

If \(\beta_T(\theta)\) and \(\beta_{\lambda}(\theta)\) are the power functions for the tests based on \(T\) and \(\lambda\), respectively, then \(\beta_T(\theta)\leq\beta_{\lambda}(\theta)\) for every \(\theta\in\Theta\);

- If the LRT is a level \(\alpha\) test, then the UIT is a level \(\alpha\) test.

Theorem 17.2 says the LRT is uniformly more powerful than the UIT. Why should we consider UIT?

UIT has a smaller Type I Error probability for every \(\theta\in\Theta_0\).

- If \(H_0\) is rejected, we may wish to look at the individual tests of \(H_{0_{\gamma}}\) to see why.

Typically the individual rejection regions \(R_{\gamma}\) are choosen so that \(\alpha_{\gamma}=\alpha\) for all \(\gamma\). In such case, the resulting IUT is a level \(\alpha\) test.

Theorem 17.2 applies only to UITs constructed from likelihood ratio tests. Theorem 17.3 applies to any IUT.

- The bound in Theorem 17.2 is the size of the LRT, which may be difficult to compute. In Theorem 17.3, any test of \(H_{0_{\gamma}}\) with known size \(\alpha_{\gamma}\) can be used and then then the upper bound on the size of the IUT is given in terms of the known sizes \(\alpha_{\gamma},\gamma\in\Gamma\).

Theorem 17.4 Consider testing \(H_0:\theta\in\bigcup_{j=1}^k\Theta_j\), where \(k\) is a finite positive integer. For each \(j=1,\cdots,k\), let \(R_j\) be the rejection region of a level \(\alpha\) test of \(H_{0_j}\). Suppose that for some \(i=1,\cdots,k\), there exists a sequence of parameter points, \(\theta_l\in\Theta_i\), \(l=1,2,\cdots\), such that

\(\lim_{l\to\infty}P_{\theta_l}(\mathbf{X}\in R_i)=\alpha\),

for each \(j=1,\cdots,k\), \(j\neq i\), \(\lim_{l\to\infty}P_{\theta_l}(\mathbf{X}\in R_j)=1\).

Proof. By Theorem 17.3, \(R\) is a level \(\alpha\) test, that is \[\begin{equation} \sup_{\theta\in\Theta_0}P_{\theta}(\mathbf{X}\in R)\leq\alpha \tag{17.10} \end{equation}\]

But, because all the parameter points \(\theta_l\) satisfy \(\theta_l\in\Theta_i\subset\Theta_0\), \[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \sup_{\theta\in\Theta_0}P_{\theta}(\mathbf{X}\in R)&\geq \lim_{l\to\infty}P_{\theta_l}(\mathbf{X}\in R)\\ =\lim_{l\to\infty}P_{\theta_l}(\mathbf{X}\in\bigcap_{j=1}^kR_j)\\ &\geq \lim_{l\to\infty}]\sum_{j=1}^kP_{\theta_l}(\mathbf{X}\in R_j)-(k-1) \quad (Bonferroni\, Inequality)\\ &=(k-1)+\alpha-(k-1)=\alpha \end{split} \tag{17.11} \end{equation}\]

This and (17.10) imply the test has size exactly equal to \(\alpha\).If \(p(\mathbf{X})\) is a valid p-value, it is easy to construct a level \(\alpha\) test based on \(p(\mathbf{X})\). The test that rejects \(H_0\) if and only if \(p(\mathbf{X})\leq \alpha\) is a level \(\alpha\) test because of (17.12).

An advantage to reporting a test result via a p-value is that each reader can choose the \(\alpha\) he or she considers appropriate and then can compare the reported p(x) to \(\alpha\) and know whether these data lead to acceptance or rejection of \(H_0\).

- The smaller the p-value, the stronger the evidence for rejecting \(H_0\). Hence, a p-value reports the results of a test on a more continuous scale, rather than just the dichotomous decision “Accept \(H_0\)” or “Reject \(H_0\)”.

The inequality in the last line is true becasue \(\mu_0\geq\mu\) and \(\frac{\mu_0-\mu}{S/\sqrt{n}}\) is a nonnegative random variable. The subscript on \(P\) is dropped because the probability does not depend on \((\mu,\sigma)\). Furthermore, \[\begin{equation} P(T_{n-1}\geq W(\mathbf{x}))=P_{\mu_0,\sigma}(\frac{\bar{X}-\mu_0}{S/\sqrt{n}}\geq W(\mathbf{x}))=P_{\mu_0,\sigma}(W(\mathbf{X})\geq W(\mathbf{x})) \tag{17.17} \end{equation}\] beacuse \(\frac{\bar{X}-\mu_0}{S/\sqrt{n}}\sim T_{n-1}\) given \(\theta=\theta_0\) and this probability is one of those considered in the calculation of the supremum in (17.13) because \((\mu_0,\sigma)\in\Theta_0\). Thus, the p-value from (17.13) for this one-sided t test is \(p(\mathbf{x})=P(T_{n-1}\geq W(\mathbf{x}))=P(T_{n-1}\geq \frac{\bar{x}-\mu_0}{s/\sqrt{n}})\).

Corollary 17.1 (p-Value Conditioning on Sufficient Statistic) Another method for definition a valid p-value involves conditioning on a sufficient statistic. Suppose \(S(\mathbf{X})\) is a sufficient statisitc for the model \(\{f(\mathbf{x}|\theta):\theta\in\Theta_0\}\). If the null hypothesis is true, the conditional distribution of \(\mathbf{X}\) given \(S=s\) does not depend on \(\theta\). Again, let \(W(\mathbf{X})\) denote a test statistic for which large values give evidence that \(H_1\) is true. Then, for each sample point \(\mathbf{x}\) define \[\begin{equation} p(\mathbf{x})=P(W(\mathbf{X})\geq W(\mathbf{x})|S=S(\mathbf{x})) \tag{17.18} \end{equation}\] Considering only the single distribution that is the conditional distribution of \(\mathbf{X}\) given \(S=s\), we see that, for any \(0\leq\alpha\leq 1\), \(P(p(\mathbf{X})\leq\alpha|S=s)\leq\alpha\). Then, for any \(\theta\in\Theta_0\), unconditionally we have \[\begin{equation} P_{\theta}(p(\mathbf{X})\leq\alpha)=\sum_{s}P(p(\mathbf{X})\leq\alpha|S=s)P_{\theta}(S=s)\leq\sum_{s}\alpha P_{\theta}(S=s)\leq\alpha \tag{17.19} \end{equation}\]

Thus, \(p(\mathbf{X})\) defined by (17.18) is a valid p-value.Example 17.9 (Fisher Exact Test) Let \(S_1\) and \(S_2\) be independent observations with \(S_1\sim Bin(n_1,p_1)\) and \(S_2\sim Bin(n_2,p_2)\). Consider testing \(H_0:p_1=p_2\) versus \(H_1:p_1>p_2\). Under \(H_0\), if we let \(p\) denote the common value of \(p_1=p_2\), the joint p.m.f. of \((S_1,S_2)\) is

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} f(s_1,s_2|p)&={{n_1} \choose {s_1}}p^{s_1}(1-p)^{n_1-s_1}{{n_2} \choose {s_2}}p^{s_2}(1-p)^{n_2-s_2}\\ &={{n_1} \choose {s_1}}{{n_2} \choose {s_2}}p^{s_1+s_2}(1-p)^{n_1+n_2-(s_1+s_2)} \end{split} \tag{17.20} \end{equation}\]

Thus, \(S=S_1+S_2\) is a sufficient statistic under \(H_0\). Given the value of \(S=s\), it is reasonable to use \(S_1\) as a test statistic and reject \(H_0\) in favor of \(H_1\) for large values of \(S_1\), because large values of \(S_1\) correspond to small values of \(S_2=s-S_1\). The conditional distribution of \(S_1\) given \(S=s\) is \(HyperGeo(n_1+n_2,n_1,s)\). Thus, the conditional p-value in (17.18) is \[\begin{equation} p(s_1,s_2)=\sum_{j=s_1}^{\min\{n_1,s\}}f(j|s) \tag{17.21} \end{equation}\] the sum of hypergeometric probabilities. The test defined by this p-value is called Fisher Exact Test.