7 Finding the Literature

Peer Review

Learning Objectives

Understand what peer review is and isn’t.

Understand the different types of scientific papers.

Understand how to find relevant scientific literature.

7.0.1 What it is

Peer review is the process of subjecting a scientific paper to criticism from experts in one’s field of study. Anyone can publish a peer-reviewed scientific paper. After you’ve written a paper, you send it to a journal that you think it fits in. If you’re writing a paper about surgery, you would send it to a surgery journal. If you’re writing a paper about fish ecology, you would send it to an ecology journal. And so on.

When it gets to the journal, an editor sees it and decides whether to send it out to reviewers. The editor is not paid for this. They do it voluntarily. If they decide to send it out for review, then they ask experts, usually 2-3 individuals, to review the paper. The experts read it, make comments, and return their reviews. They do this individually and are not paid for it. They review voluntarily.

After the reviews come back, the editor must make a decision. Usually, the decision is either to reject the paper, in which case the authors must find another journal to publish in, or to require the authors to revise the paper according to the reviewer’s suggestions. The authors revise the paper and send it back to the editor. The editor then either accepts it or sends it back to the reviewers to see if they have any other concerns. If they do not, then the editor makes a decision on whether to accept the paper for the journal. The whole process takes at least two-three months. In the end, the editor may still reject the paper and the author’s then start anew at a different journal (after revising it of course, since they may get similar reviewers as the original journal).

Once the paper is accepted, it will get assigned to a volume of the journal and published along with other papers. Only then is a paper considered to be a peer-reviewed published paper. The authors do not get paid for this. In fact, in many cases the authors or their institutions must pay the journal to publish the paper. The journal then charge readers to read the papers. In this system, only the journal publishers get paid for this.

7.0.2 What it isn’t

Peer review does not guarantee that a paper’s results are correct. It means that at least a handful of other experts have read the paper an deemed it sufficient to be published in a journal. Getting published is no easy task in science. It is common for papers to get rejected from multiple journals before they are finally accepted, a process that can take years from the initial submission of the authors. Rejection doesn’t mean that the work is not important. Consider Edward Jenner, who discovered vaccination against smallpox. He tried to publish his results in 1797, but the paper was rejected. Reviewers thought he needed more examples of his vaccination procedures (i.e. more replicates). He obtained them and later published his work in a journal a few years later (Riedel 2005).

Peer review does not guarantee that a published result is correct, either. In fact, many scientific ideas turn out to be wrong. This was famously reported in an analysis by John Ioannidis provocatively titled “Why most published research findings are false” (Ioannidis 2005). There is a lot of debate about whether this is strictly true and, more importantly, why. One obvious explanation is that science has always learned as much or more from its failures as from its successes. It is hard to proceed any other way. By definition, scientific studies reveal and study new ideas and phenomena. If we already knew the answers to these ideas ahead of time and the science always got the right answer, then we wouldn’t actually need science at all. Consider another truism from economics: Most Small Businesses Fail. Just like there are lots of ideas out there, there are also lots of businesses, many of which won’t succeed. But like economics, our best hope is that the best succeed on average over time and we tend to end up with better ideas (and businesses) in the end.

Primary versus Secondary versus whatever you just Googled.

Scientific studies are generally reported as either primary literature or secondary literature. Primary literature consists of scientific papers that collect data, analyze it, and report on the outcome. Secondary literature consists of scientific papers that report or comment on already published findings. It includes things like Reviews, Commentary, or Meta-Analyses. When you find a scientific paper, it is sometimes labeled as a “Review” or “Commentary” or something else. In those cases, it is simple to identify a secondary source. More often, papers are not labeled clearly and you’ll have to do more work. Here are some tips for deciding whether your paper is primary or secondary.

I just googled it - This stuff about primary versus secondary assumes that you’ve been able to find an actual scientific paper that is peer-reviewed. If you completed your search on Google, then it is very difficult to tell what’s real versus junk.

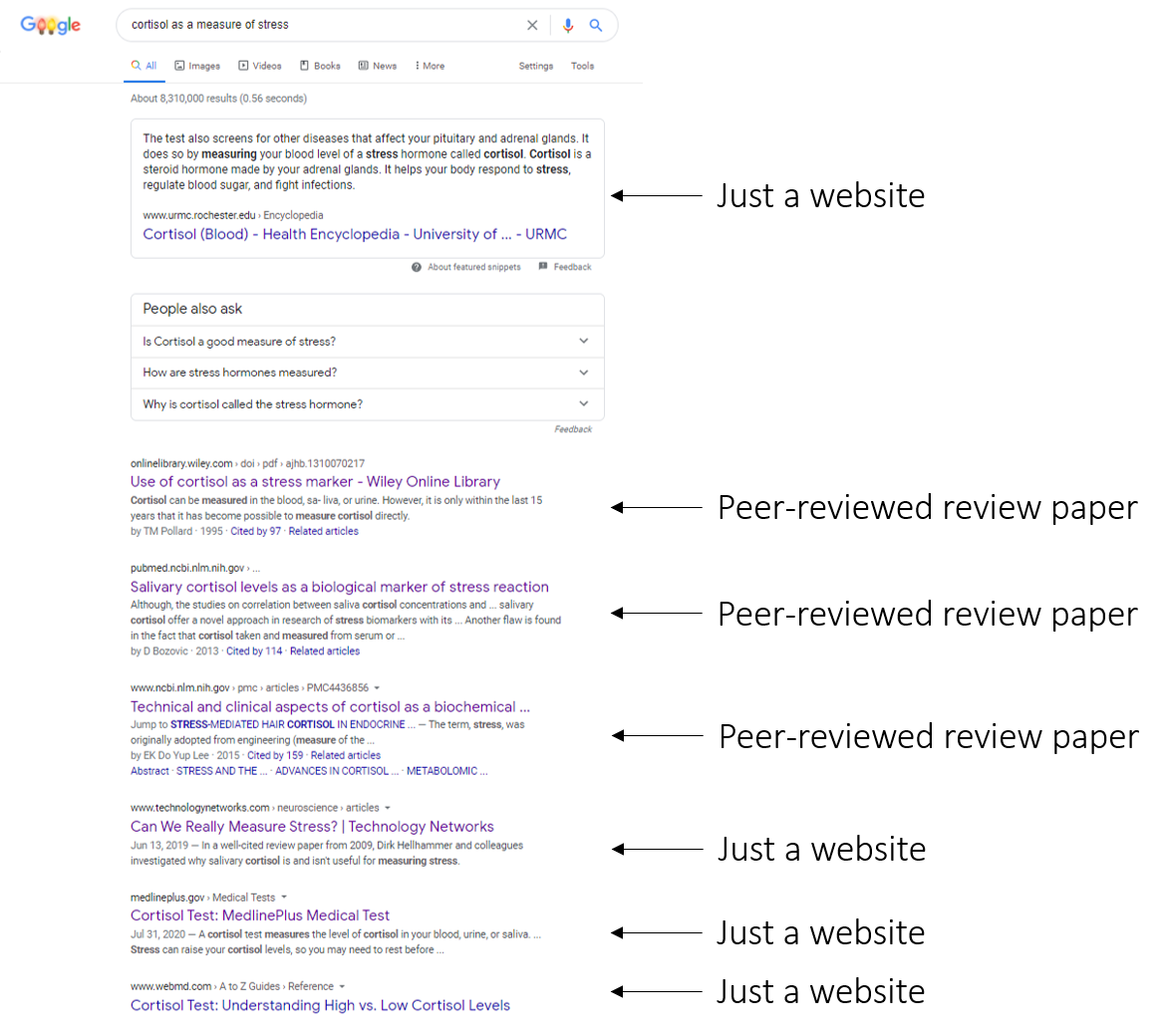

Here’s an example. We searched Google for “cortisol as a measure of stress”. These are the results.

Figure 7.1: Search results from www.google.com

The first page lists seven results, four of which are just websites. It’s not that those websites are “bad” or “wrong”, they just aren’t presenting scientific research. They are presenting whatever the creators want to put up there. In addition, three results contain peer-reviewed papers. They are all secondary papers that provide reviews of cortisol. More importantly, none of them link directly to the actual paper. They link to the NCBI database, which contains only abstracts. We would have to do more work to find the original pdf of the paper and read it. This is inefficient.

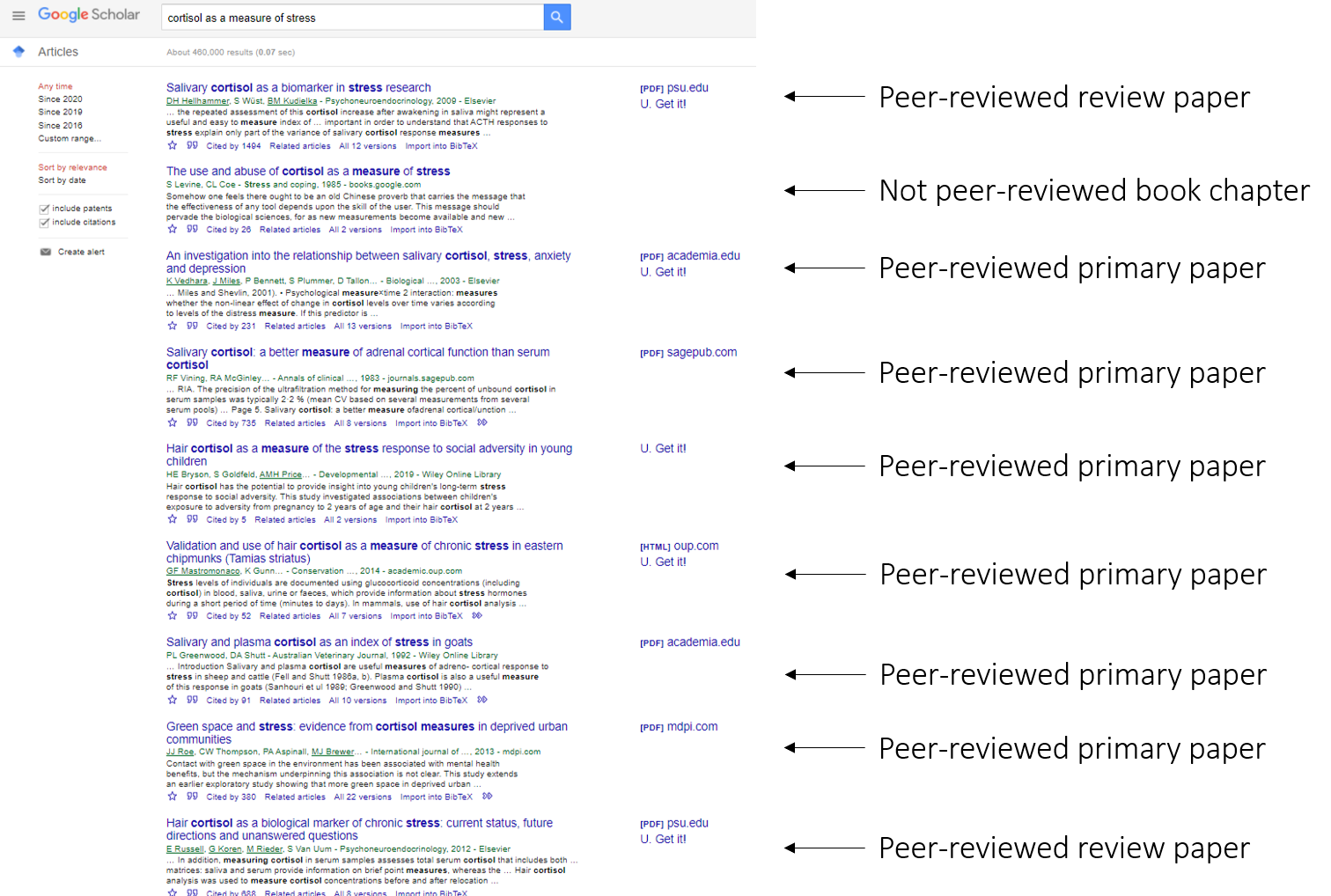

Even Google knows that this is not a good way to find scientific literature. That’s why they created an entirely different search engine called Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com. Here is the same search as above, but now on Google Scholar.

Figure 7.2: Search results from www.google.com

Notice how you get a completely different set of results than searching on just www.google.com. All results except one (a book chapter) are peer-reviewed papers. Most are primary literature. Many contain a direct link to the pdf. Just by using the proper search engine, we made life a lot easier. If you haven’t bookmarked Google Scholar, do it now.

Is this a primary or secondary paper?

Look in the Abstract

Do you see statements that indicate that the authors collected original data? Something like…“We sampled ten forests for bird calls…” or “We measured flowering rate in response to …” or “Cortisol was measured in 2 birds from each of 10 nests…”. If so, then you’ve found primary literature.

Do you see statements that indicate that the authors are summarizing already published results? Something like…“Here, we review evidence for bird calls in forests using a systematic review…” or “We extracted data from 112 published studies to analyze the effect of watering on flowering rates…” or “We discuss the challenges of using cortisol as a proxy for stress…”. If so, then you’ve probably found secondary literature.

Look in the Methods

Do you see detailed information on experimental design or data collection from the field? If so, then you’ve probably found primary literature.

Are the methods missing? Does the paper also lack other common sections, like Results, Statistical Analysis, etc? If so, then you’ve probably found a review paper or a commentary.

Do you see information that discusses how the authors searched the literature and extracted data? If so, then you’ve probably found a meta-analysis.

Why does it matter?

On a practical level, you’re science professors may often require a certain number of papers that you cite to be Primary or Secondary. Using the quick tips above will just save you a lot of worry when you write a paper for a class.

More broadly, it is important to recognize different types of literature when you’re building a case for your own study in the introduction. A common mistake we see is for students to overuse opinion papers. We get it. Those types of papers often are easier to find and easier to read. They seem to make complex science seem settled and easy. They also come with the stamp of approval from a journal. There is nothing wrong with using and citing those types of papers occasionally. But they also won’t contain all of the messy details of the primary literature they are meant to summarize. Our view is that we can’t really assess a review paper well unless we’re already familiar with the primary literature on which its based. If all we read is a review or an opinion piece, and then cite that as justifying our study, then we haven’t built a very good foundation on which to base our study.

By contrast, the primary literature represents findings from a single study. They are building blocks on which future science is built. They contain all of the methodological details. We can use those details to judge how much we agree with their work and conclusions. But because they are single studies, we also need to read several other studies to get a sense of how surprising the results in a single paper are.

Primary and secondary literature represent a dance that is taking place in the scientific community. When experts read and publish primary research articles, they may notice important points that are routinely missed. Then they write opinion or commentary pieces to highlight those points. But if they are labeled as opinions, the are just that. You are free to disagree with them and form your own opinion. But you can’t do that until you understand the primary literature first. That is the dance that produces all of those weird college syllabi that specify X number of primary versus secondary sources. It’s not to make a trivial target. It’s to encourage you to delve deep into a few ideas at all levels of their production.

You do not need to pay for journal articles

It is common to find a paper that you want to read, only to click on it and be given a paywall. Don’t pay it. Ever. If you are at a university, then your university likely has access to the papers from that journal. If they don’t, then they can get a copy through interlibrary loan, which is a process by which different libraries share material that one library subscribes to and another library doesn’t. Nearly all universities have some version of this system. As a student, you pay fees to support access to science. Learn your system and use it!

If all else fails, you can even try emailing the author directly. Everyone is happy to share their work (it’s why scientists write after all). Ask them for a copy and they’ll gladly send it to you.