Field lab 5. Estimating population density and biodiversity

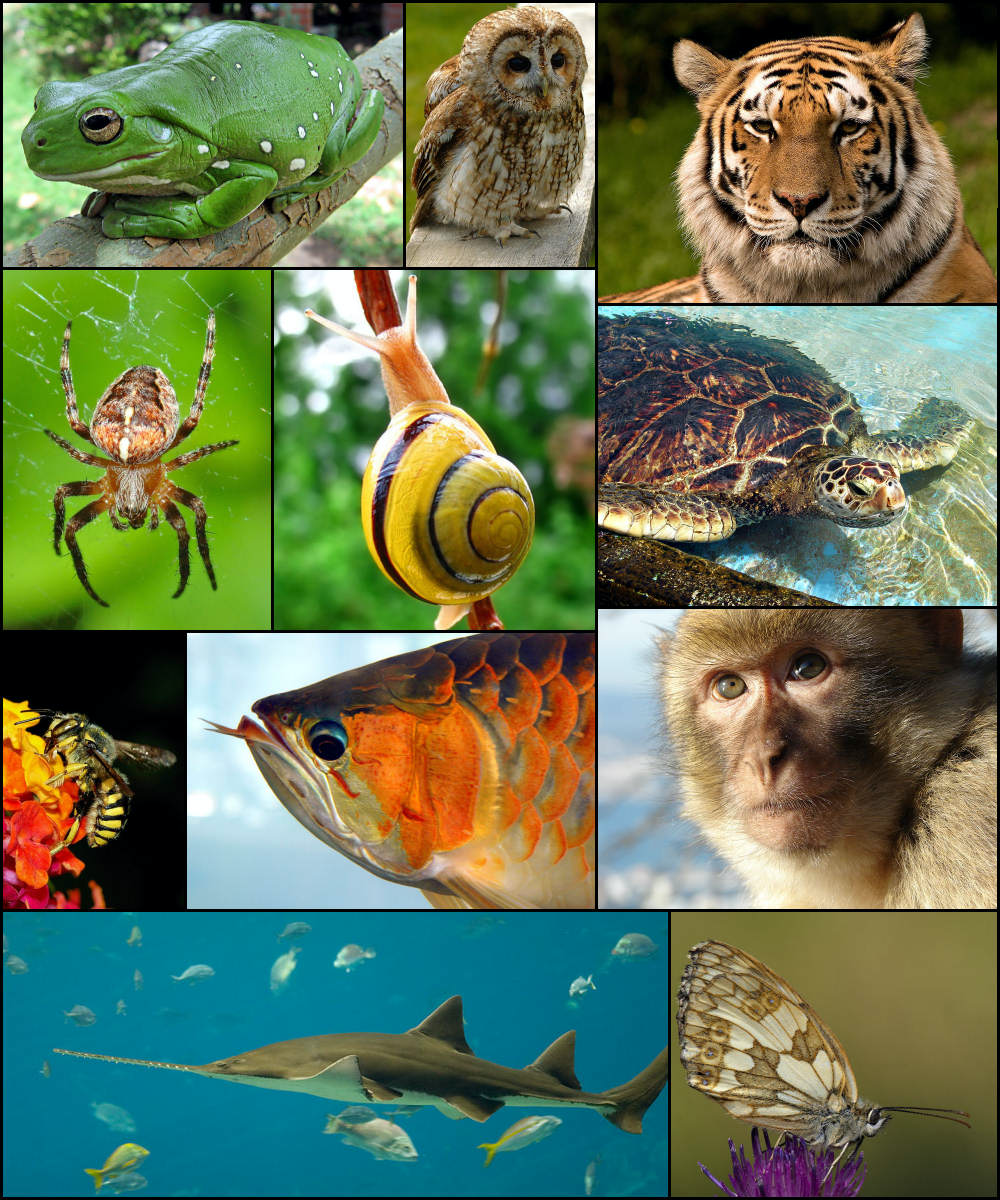

Figure 11: Biodiversity image; Justin / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

Part 1. Background

In lecture this week we learned about population- and community- level interactions, and how they can influence individual and species-specific behavior. Differences in population density can lead to shifts in the proportion of different behavioral phenotypes in a population, and the presence of competitors of other species can shape the behavior of animals on shorter (ecological) and longer (evolutionary) time scales.

For many types of behavioral studies—and for effective conservation of animals— a clear estimate of population density of focal species along with estimates of overall biodiversity of an area are necessary. In the field lab this week you will become familiar with field methods scientists use to estimate population density and biodiversity. There are many different methods and approaches that scientists can use, and the methods we will use in this lab are most appropriate for studies of terrestrial vertebrates.

Part 2. Estimating distance

A crucial part of the approach we will use today is the ability to estimate how far animals are away from you. If we were doing this activity for a scientific study, we would use a range finder to get accurate estimates. But, we can also use the number of steps we take to estimate distance. The best way to do this is to use a tape measure to estimate your stride length (or distance covered in a single step) in meters. If this is not possible, and you have an app on your phone that tracks distance and number of steps you could divide the distance of your last walk (in meters)/number of steps. Or you can visit this website (http://www.kylesconverter.com/length/steps-to-meters).

Question 1. What did you estimate your stride length to be in meters? Which approach did you use to estimate this?

Part 3. Designing your study

You and your partner will develop testable research questions related to both population density of a focal species, and overall biodiversity. You and your partner do not need to focus on the same species, as depending on your geographic location this may not be possible. You will conduct the census twice in two distinct habitats (it could be as simple as your front and back yard, different streets, the edge versus the center of a park, etc.). Ideally, the length of each census will be 500 meters and in a straight line, but you can do shorter or longer depending on your location and limitations. To control for potential differences in animal circadian rhythms, it would be best to conduct your censuses at the same time (e.g. both in the morning). As always, if you do not feel you can do this activity safely please contact me for a virtual alternative.

Part 3a. Population density

For this section you and your partner will each choose a target focal species. It can be the same species or a different species. Choose one that is relatively common so that you will actually get some data! Before you start data collection please answer the questions below.

Question 2. What is your focal species? Which habitats will you be censusing? Which habitat do you predict will have higher population density of your focal species, and why? How long will your census route be?

Part 3b. Estimating biodiversity

In a perfect world we would be able to inventory all of the animals (insects, reptiles, birds, mammals) in an area. But oftentimes, this is not possible due to the immense diversity of species (particularly in the tropics). Depending on the research question or conservation goals is common to focus on a subset of animals (e.g. birds, mammals etc.) to estimate diversity. For this exercise you will compare biodiversity estimates from four different census routes- the two sites that you chose and the two sites that your partner chose. Before we begin please answer the questions below.

Question 3. What are the four habitat types you and your partner will be censusing? Which habitat do you predict will have the highest biodiversity? Which do you predict will have the lowest? Will you focus on birds, mammals or a combination?

Part 4. Collecting your data

To be good scientists make sure to note the date, time, weather, the total distance (in meters) of your census route, and any other notes in your notebook. You can keep track of the distance you walked either by using an app on your phone or by counting your steps. For each animal encountered along the transect note the following information:

Species: I assume for your focal species you will be able to identify to the species. If you encounter birds or animals that you cannot identify to species assign them to their own categories (e.g. small black bird, large black bird).

Distance (in meters) along your census line: Did you see the animal at the start of your census? Then the distance would be 0 or 1 meters. If you saw it at the end it would be 500 meters.

Perpendicular distance from you census line: How far (in meters) was the animal away from you when you detected it? You can estimate this by counting the number of steps away the animal is from your census line.

Method of detection: Did you see the animal, hear the animal, step on it?

Question 4. What were your general observations? Do you feel confident that you were able to detect all the animals on the census route? What could have potentially biased your results?

Question 5. How could inter-individual differences in behavior potentially influence the results of your survey?

Part 5. Data analysis

We will be analyzing the data during the computer lab. Be sure that your data are entered into the data sheet following the correct format.

Material for this lab was adapted from: Andrew J. Marshall’s Primate Evolutionary Ecology course at University of California, Davis.