Chapter 3 Basic modelling in R

Creating a model is an essential part of forecasting and data analysis. I’ve put together a quick guide on my process for modelling data and checking model fit. The source data I use in this example is Melbourne’s weather record over a 12 month period. Daily temperature is based on macroscale weather and climate systems, however many observable measurements are correlated (i.e. hot days tend to have lots of sunshine). This makes using weather data great for model building.

3.1 Source, format, and plot data

Before we get started, it is useful to have some packages up and running.

#Useful packages for regression

library(readr)

library(readxl)

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

library(tidyverse)

library(lubridate)

library(modelr)

library(cowplot)I’ve put together a csv file of weather observations in Melbourne in 2019. We begin our model by downloading the data from Github.

#Input data

url <-"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/charlescoverdale/predicttemperature/master/MEL_weather_2019.csv"

#We'll read this data in as a dataframe. The 'check.names' function set to false means the funny units that the BOM use for column names won't affect the import.

MEL_weather_2019 <- read.csv(url, check.names = F)

head(MEL_weather_2019)This data is relatively clean. One handy change to make is to make the date into a dynamic format (to easily switch between months, years, etc).

#Add a proper date column

MEL_weather_2019 <- MEL_weather_2019 %>%

mutate(Date = make_date(Year, Month, Day))We also notice that some of the column names have symbols in them. This can be tricky to work with, so let’s rename some columns into something more manageable.

#Rename key df variables

names(MEL_weather_2019)[4]<- "Solar_exposure"

names(MEL_weather_2019)[5]<- "Rainfall"

names(MEL_weather_2019)[6]<- "Max_temp"

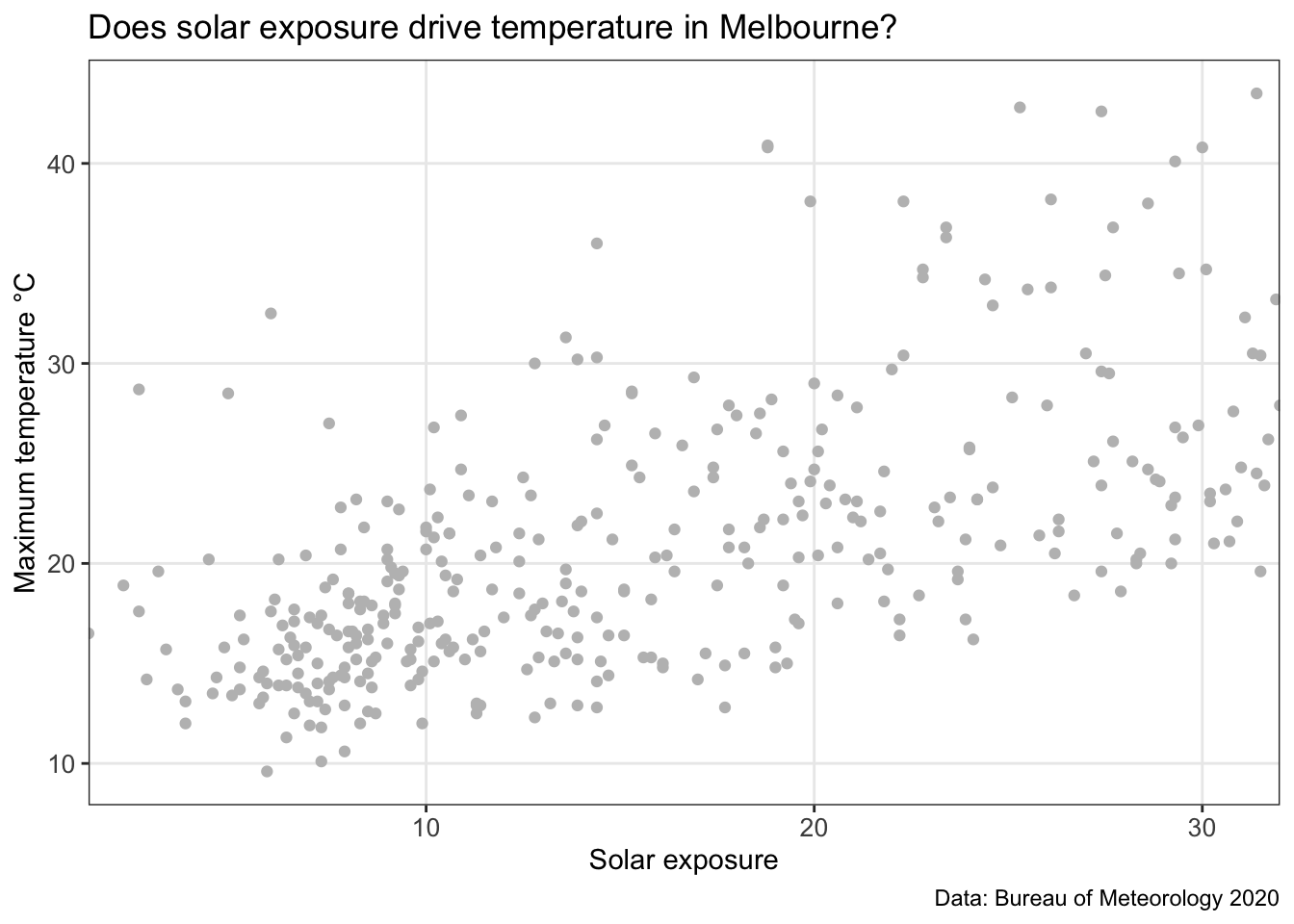

head(MEL_weather_2019)We’re aiming to investigate if other weather variables can predict maximum temperatures. Solar exposure seems like a plausible place to start. We start by plotting the two variables to if there is a trend.

#Plot the data

MEL_temp_investigate <- ggplot(MEL_weather_2019)+

geom_point(aes(y=Max_temp, x=Solar_exposure),col="grey")+

labs(title = "Does solar exposure drive temperature in Melbourne?",

caption = "Data: Bureau of Meteorology 2020") +

xlab("Solar exposure")+

ylab("Maximum temperature °C")+

scale_x_continuous(expand=c(0,0))+

theme_bw()+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=10))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())

MEL_temp_investigate

Eyeballing the chart above, there seems to be a correlation between the two data sets. We’ll do one more quick plot to analyse the data. What is the distribution of temperature?

ggplot(MEL_weather_2019, aes(x=Max_temp)) +

geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..), colour="black", fill="lightblue")+

geom_density(alpha=.5, fill="grey",colour="darkblue")+

scale_x_continuous(breaks=c(5,10,15,20,25,30,35,40,45),

expand=c(0,0))+

xlab("Temperature")+

ylab("Density")+

theme_bw()+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=12))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())

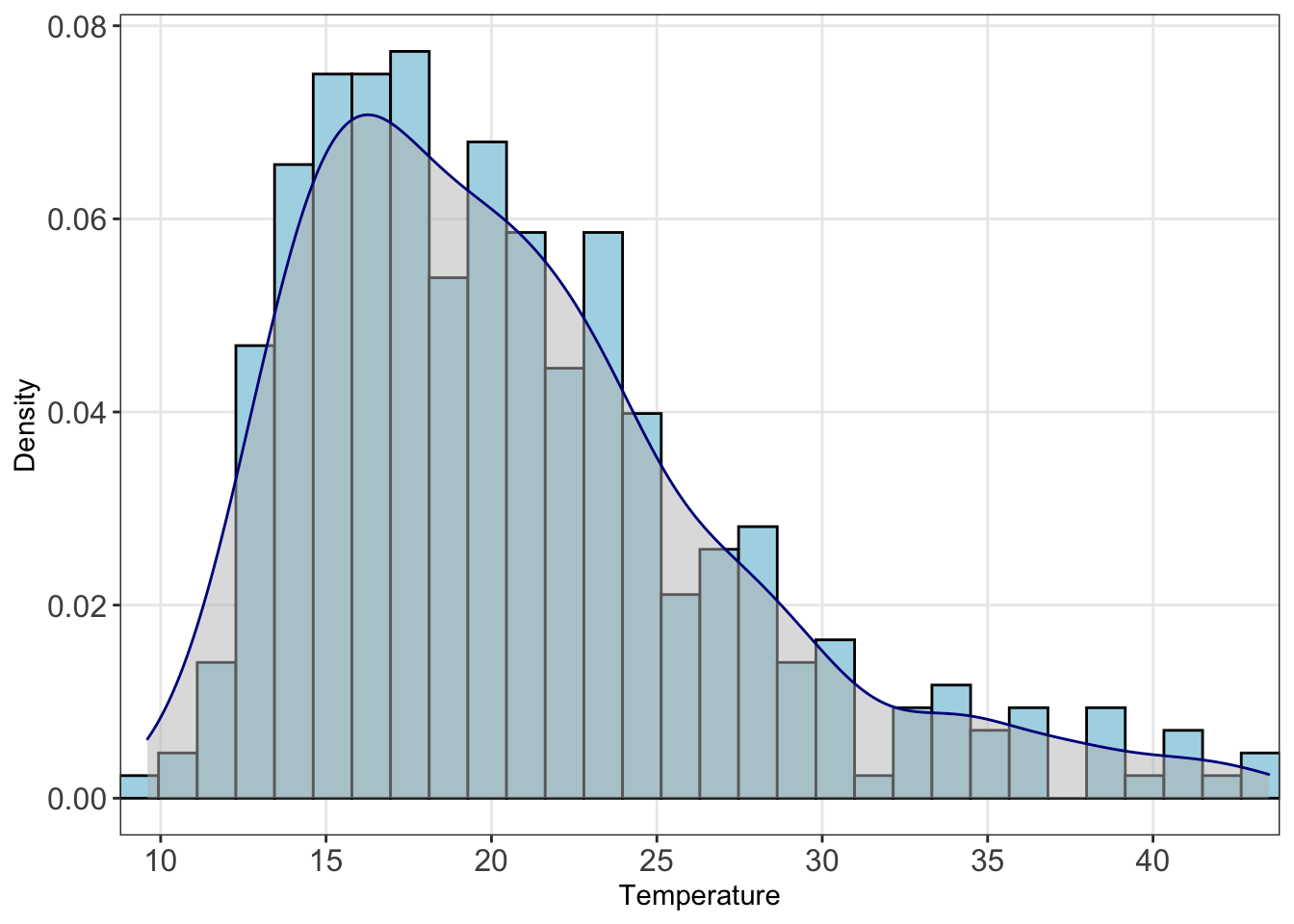

We can see here the data is right skewed (i.e. the mean will be greater than the median). We’ll need to keep this in mind. Let’s start building a model.

3.2 Build a linear model

We start by looking whether a simple linear regression of solar exposure seems to be correlated with temperature. In R, we can use the linear model (lm) function.

#Create a straight line estimate to fit the data

temp_model <- lm(Max_temp~Solar_exposure, data=MEL_weather_2019)3.3 Analyse the model fit

Let’s see how well solar exposure explains changes in temperature

#Call a summary of the model

summary(temp_model)The adjusted R squared value (one measure of model fit) is 0.3596. Furthermore the coefficient of our solar_exposure variable is statistically significant.

3.4 Compare the predicted values with the actual values

We can use this lm function to predict values of temperature based on the level of solar exposure. We can then compare this to the actual temperature record, and see how well the model fits the data set.

#Use this lm model to predict the values

MEL_weather_2019 <- MEL_weather_2019 %>%

mutate(predicted_temp=predict(temp_model,newdata=MEL_weather_2019))

#Calculate the prediction interval

prediction_interval <- predict(temp_model,

newdata=MEL_weather_2019,

interval = "prediction")

summary(prediction_interval)

#Bind this prediction interval data back to the main set

MEL_weather_2019 <- cbind(MEL_weather_2019,prediction_interval)

MEL_weather_2019Model fit is easier to interpret graphically. Let’s plot the data with the model overlaid.

#Plot a chart with data and model on it

MEL_temp_predicted <-

ggplot(MEL_weather_2019)+

geom_point(aes(y=Max_temp, x=Solar_exposure),

col="grey")+

geom_line(aes(y=predicted_temp,x=Solar_exposure),

col="blue")+

geom_smooth(aes(y=Max_temp, x= Solar_exposure),

method=lm)+

geom_line(aes(y=lwr,x=Solar_exposure),

colour="red", linetype="dashed")+

geom_line(aes(y=upr,x=Solar_exposure),

colour="red", linetype="dashed")+

labs(title =

"Does solar exposure drive temperature in Melbourne?",

subtitle = 'Investigation using linear regression',

caption = "Data: Bureau of Meteorology 2020") +

xlab("Solar exposure")+

ylab("Maximum temperature °C")+

scale_x_continuous(expand=c(0,0),

breaks=c(0,5,10,15,20,25,30,35,40))+

theme_bw()+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=10))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())

MEL_temp_predicted

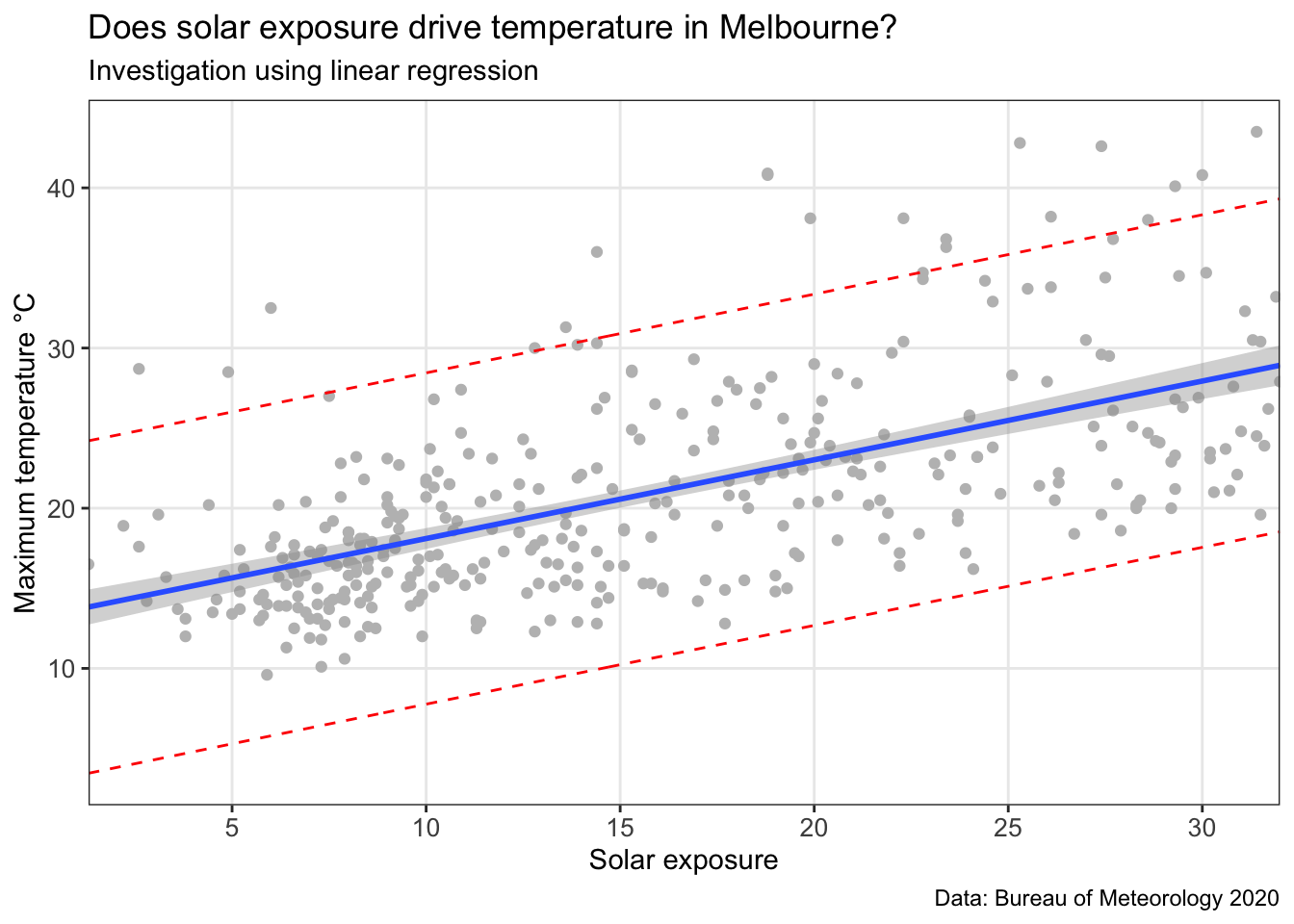

This chart includes the model (blue line), confidence interval (grey band around the blue line), and a prediction interval (red dotted line). A prediction interval reflects the uncertainty around a single value (put simple: what is the reasonable upper and lower bound that this data point could be estimated at?). A confidence interval reflects the uncertainty around the mean prediction values (put simply: what is a reasonable upper and lower bound for the blue line at this x value?). Therefore, a prediction interval will be generally much wider than a confidence interval for the same value.

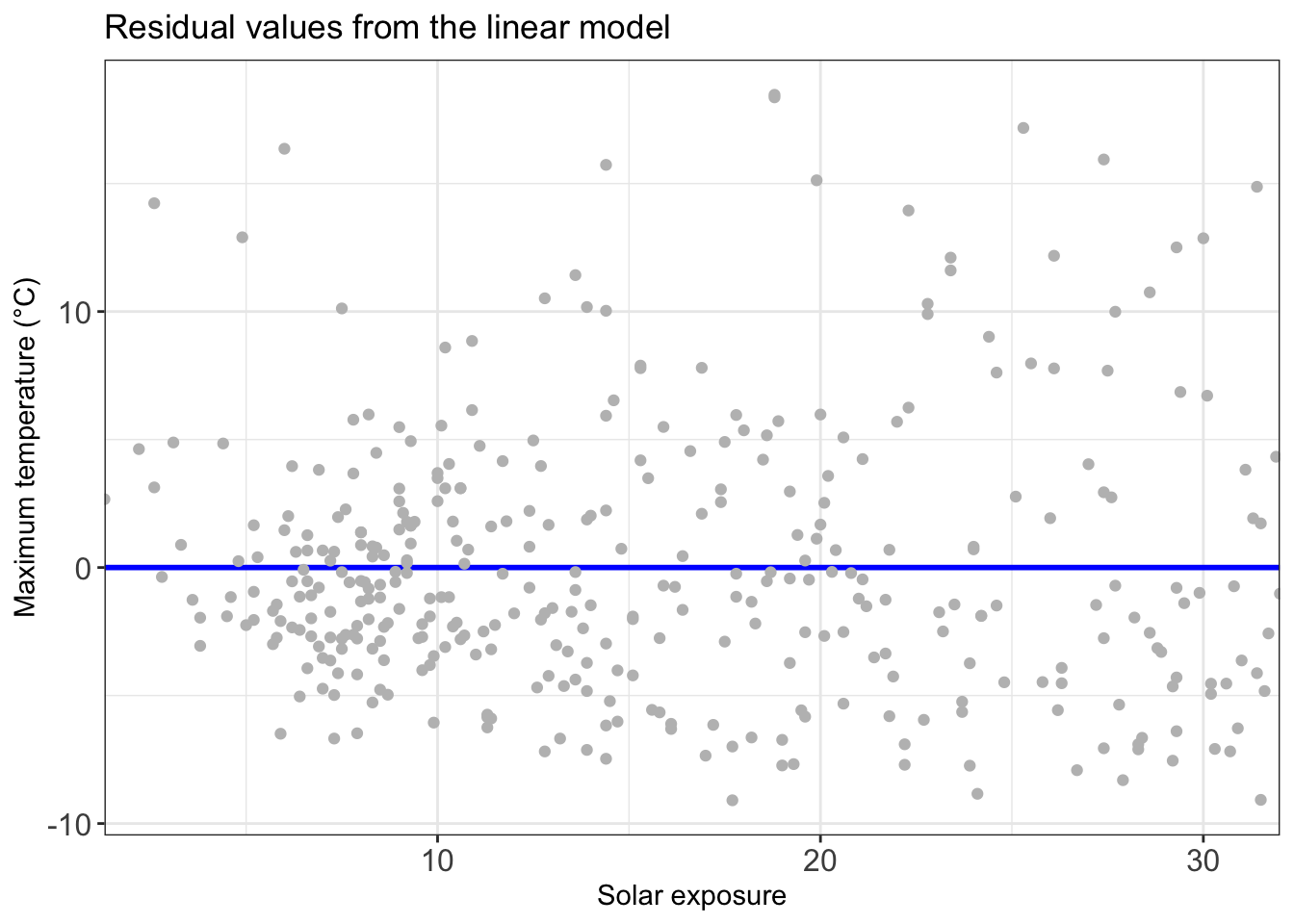

3.5 Analyse the residuals

#Add the residuals to the series

residuals_temp_predict <- MEL_weather_2019 %>%

add_residuals(temp_model)Plot these residuals in a chart.

residuals_temp_predict_chart <-

ggplot(data=residuals_temp_predict,

aes(x=Solar_exposure, y=resid), col="grey")+

geom_ref_line(h=0,colour="blue", size=1)+

geom_point(col="grey")+

xlab("Solar exposure")+

ylab("Maximum temperature (°C)")+

theme_bw() +

labs(title = "Residual values from the linear model")+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=12))+

scale_x_continuous(expand=c(0,0))

residuals_temp_predict_chart

3.6 Linear regression with more than one variable

The linear model above is *okay*, but can we make it better? Let’s start by adding in some more variables into the linear regression.

Rainfall data might assist our model in predicting temperature. Let’s add in that variable and analyse the results.

temp_model_2 <-

lm(Max_temp ~ Solar_exposure + Rainfall, data=MEL_weather_2019)

summary(temp_model_2)We can see that adding in rainfall made the model better (R squared value has increased to 0.4338).

Next, we consider whether solar exposure and rainfall might be related to each other, as well as to temperature. For our third temperature model, we add an interaction variable between solar exposure and rainfall.

temp_model_3 <- lm(Max_temp ~ Solar_exposure +

Rainfall +

Solar_exposure:Rainfall,

data=MEL_weather_2019)

summary(temp_model_3)We now see this variable is significant, and improves the model slightly (seen by an adjusted R squared of 0.4529).

3.7 Fitting a polynomial regression

When analysing the above data set, we see the issue is the sheer variance of temperatures associated with every other variable (it turns out weather forecasting is notoriously difficult).

However we can expect that temperature follows a non-linear pattern throughout the year (in Australia it is hot in January-March, cold in June-August, then starts to warm up again). A linear model (e.g. a straight line) will be a very bad model for temperature — we need to introduce polynomials.

For simplicity, we will introduce a new variable (Day_number) which is the day of the year (e.g. 1 January is #1, 31 December is #366).

MEL_weather_2019 <- MEL_weather_2019 %>%

mutate(Day_number=row_number())

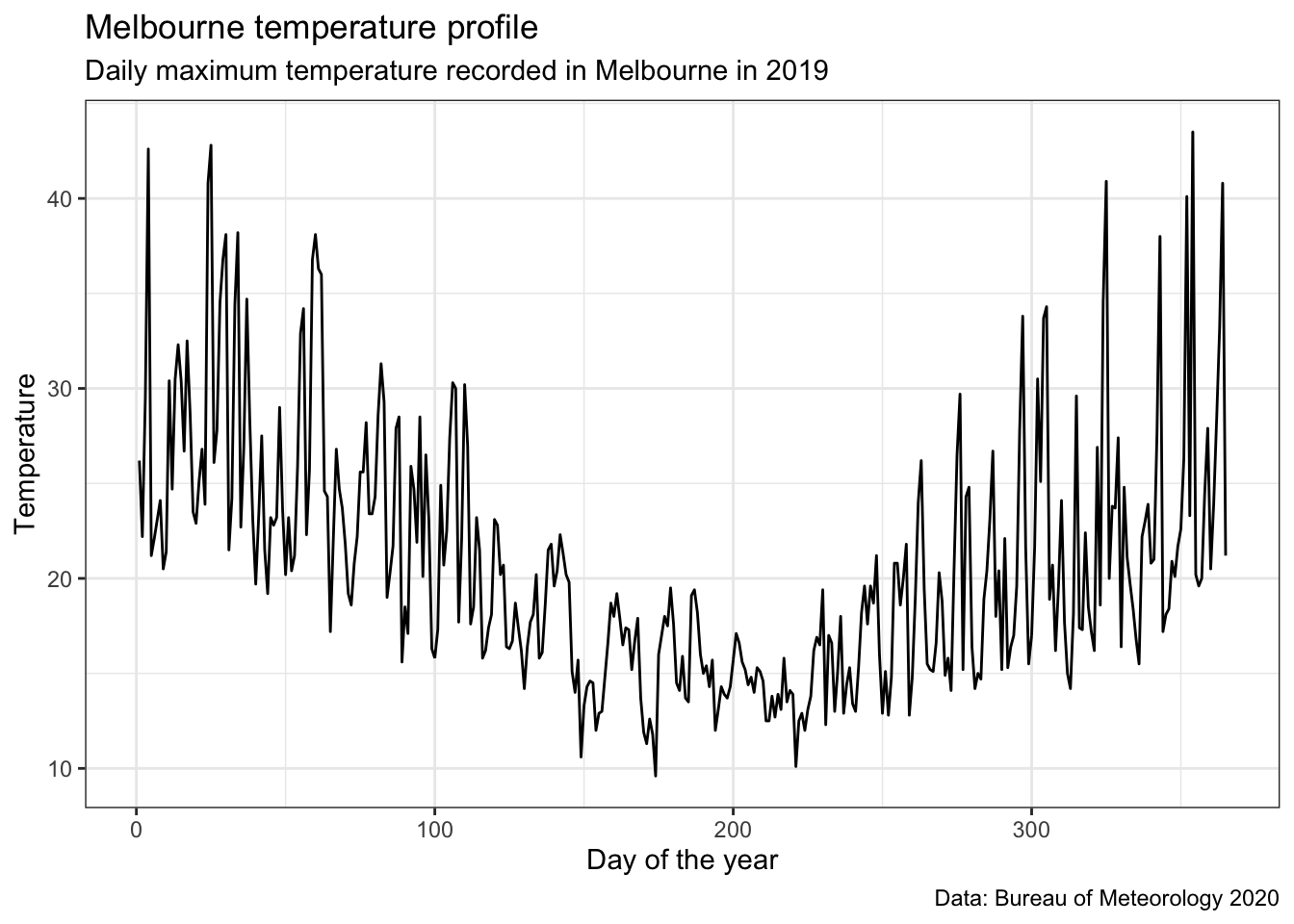

head(MEL_weather_2019)Using the same dataset as above, let’s plot temperature in Melbourne in 2019.

MEL_temp_chart <-

ggplot(MEL_weather_2019)+

geom_line(aes(x = Day_number, y = Max_temp)) +

labs(title = 'Melbourne temperature profile',

subtitle = 'Daily maximum temperature recorded in Melbourne in 2019',

caption = "Data: Bureau of Meteorology 2020") +

xlab("Day of the year")+

ylab("Temperature")+

theme_bw()

MEL_temp_chart

We can see we’ll need a non-linear model to fit this data.

Below we create a few different models. We start with a normal straight line model, then add an x² and x³ model. We then use these models and the ‘predict’ function to see what temperatures they forecast based on the input data.

#Create a straight line estimate to fit the data

poly1 <- lm(Max_temp ~ poly(Day_number,1,raw=TRUE),

data=MEL_weather_2019)

summary(poly1)

#Create a polynominal of order 2 to fit this data

poly2 <- lm(Max_temp ~ poly(Day_number,2,raw=TRUE),

data=MEL_weather_2019)

summary(poly2)

#Create a polynominal of order 3 to fit this data

poly3 <- lm(Max_temp ~ poly(Day_number,3,raw=TRUE),

data=MEL_weather_2019)

summary(poly3)

#Use these models to predict

MEL_weather_2019 <- MEL_weather_2019 %>%

mutate(poly1values=predict(poly1,newdata=MEL_weather_2019))%>%

mutate(poly2values=predict(poly2,newdata=MEL_weather_2019))%>%

mutate(poly3values=predict(poly3,newdata=MEL_weather_2019))

head(MEL_weather_2019)In the table above we can see the estimates for that data point from the various models.

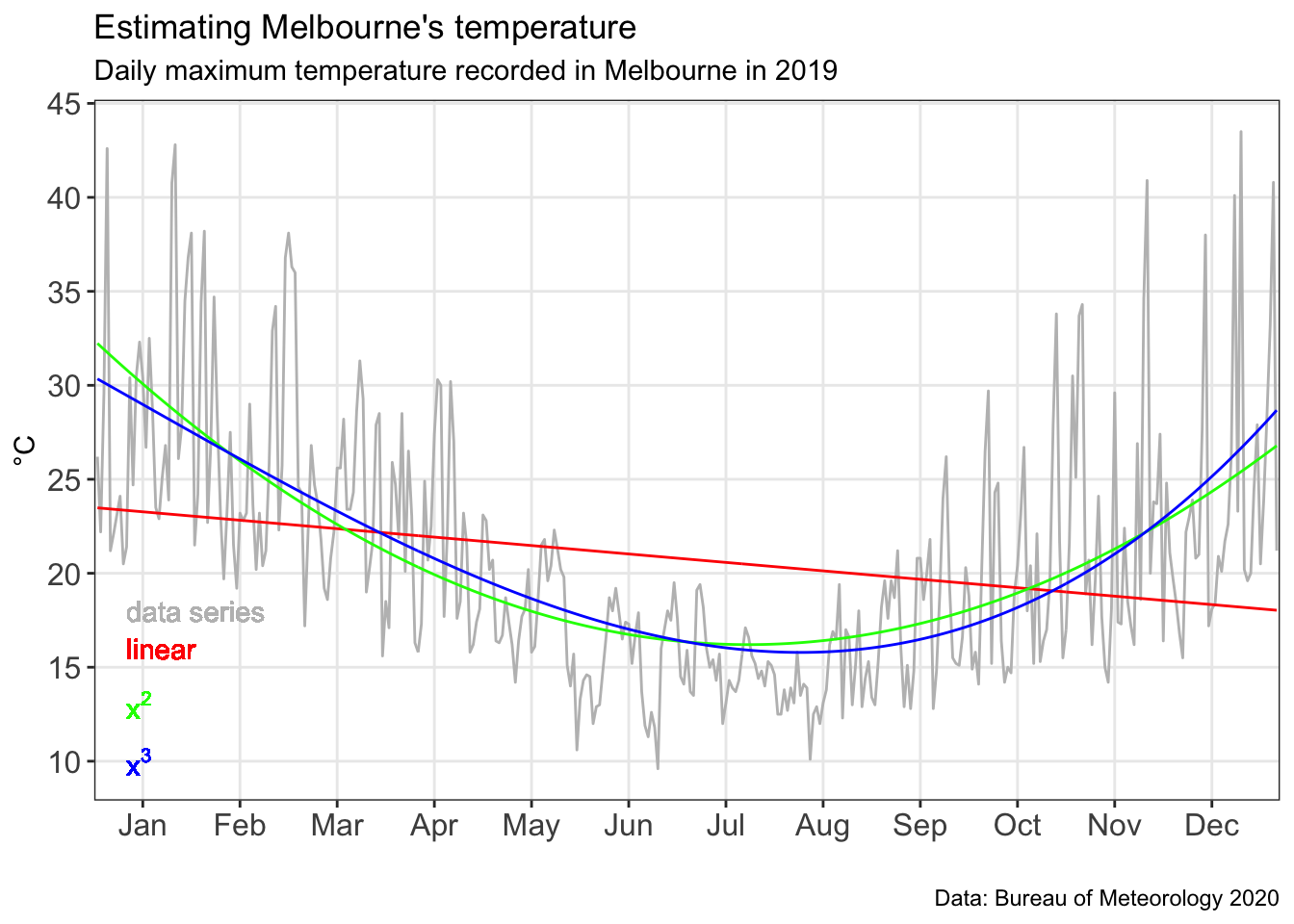

To see how well the models did graphically, we can plot the original data series with the polynominal models overlaid.

#Plot a chart with all models on it

MEL_weather_model_chart <-

ggplot(MEL_weather_2019)+

geom_line(aes(x=Day_number, y= Max_temp),col="grey")+

geom_line(aes(x=Day_number, y= poly1values),col="red") +

geom_line(aes(x=Day_number, y= poly2values),col="green")+

geom_line(aes(x=Day_number, y= poly3values),col="blue")+

#Add text annotations

geom_text(x=10,y=18,label="data series",col="grey",hjust=0)+

geom_text(x=10,y=16,label="linear",col="red",hjust=0)+

geom_text(x=10,y=13,label=parse(text="x^2"),col="green",hjust=0)+

geom_text(x=10,y=10,label=parse(text="x^3"),col="blue",hjust=0)+

labs(title = "Estimating Melbourne's temperature",

subtitle = 'Daily maximum temperature recorded in Melbourne in 2019',

caption = "Data: Bureau of Meteorology 2020") +

xlim(0,366)+

ylim(10,45)+

scale_x_continuous(breaks=

c(15,45,75,105,135,165,195,225,255,285,315,345),

labels=c("Jan", "Feb", "Mar", "Apr", "May", "Jun", "Jul", "Aug", "Sep", "Oct", "Nov", "Dec"),

expand=c(0,0),

limits=c(0,366)) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks=c(10,15,20,25,30,35,40,45)) +

xlab("")+

ylab("°C")+

theme_bw()+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=12))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())

MEL_weather_model_chart

We can see in the chart above the polynomial models do much better at fitting the data. However, they are still highly variant.

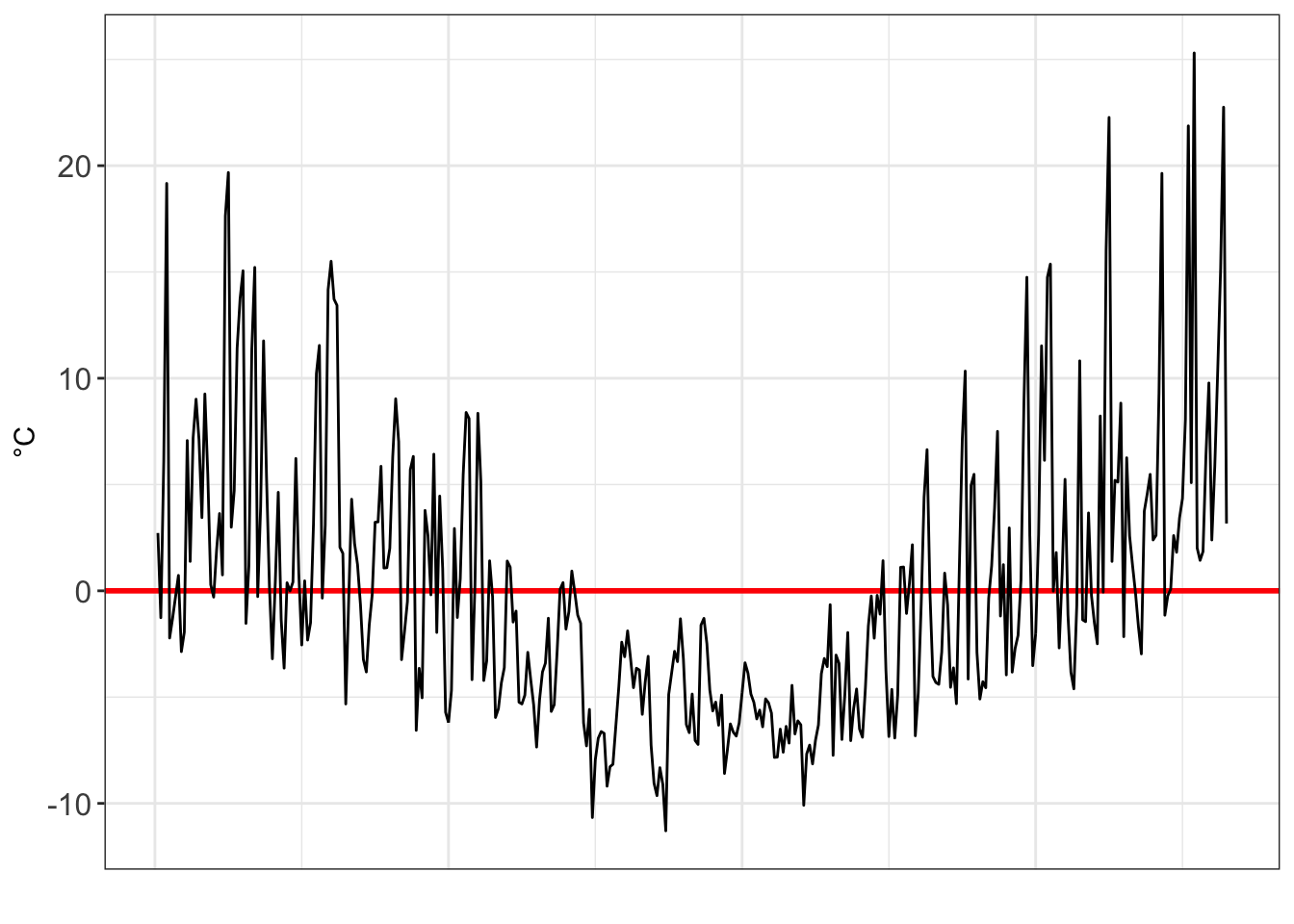

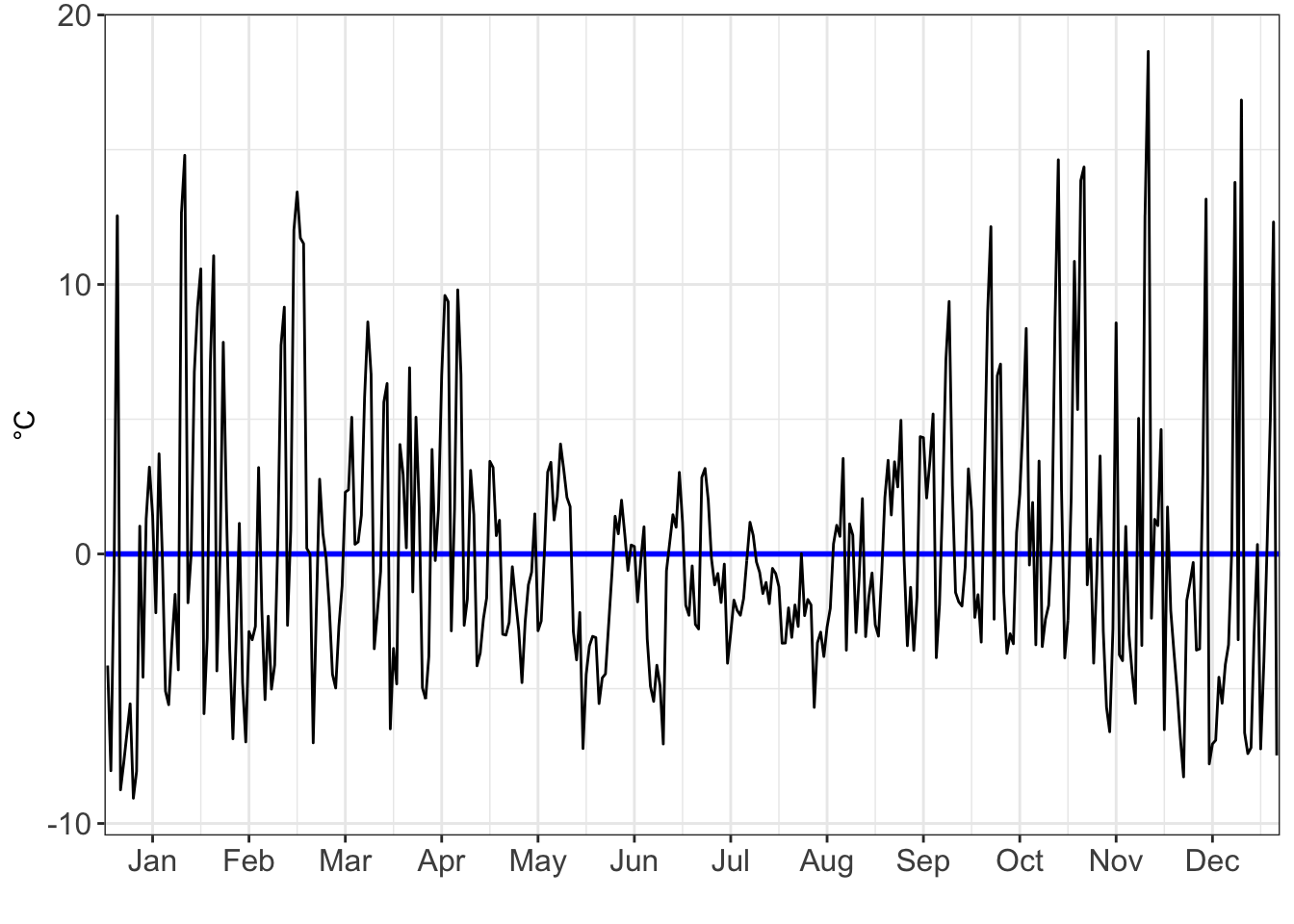

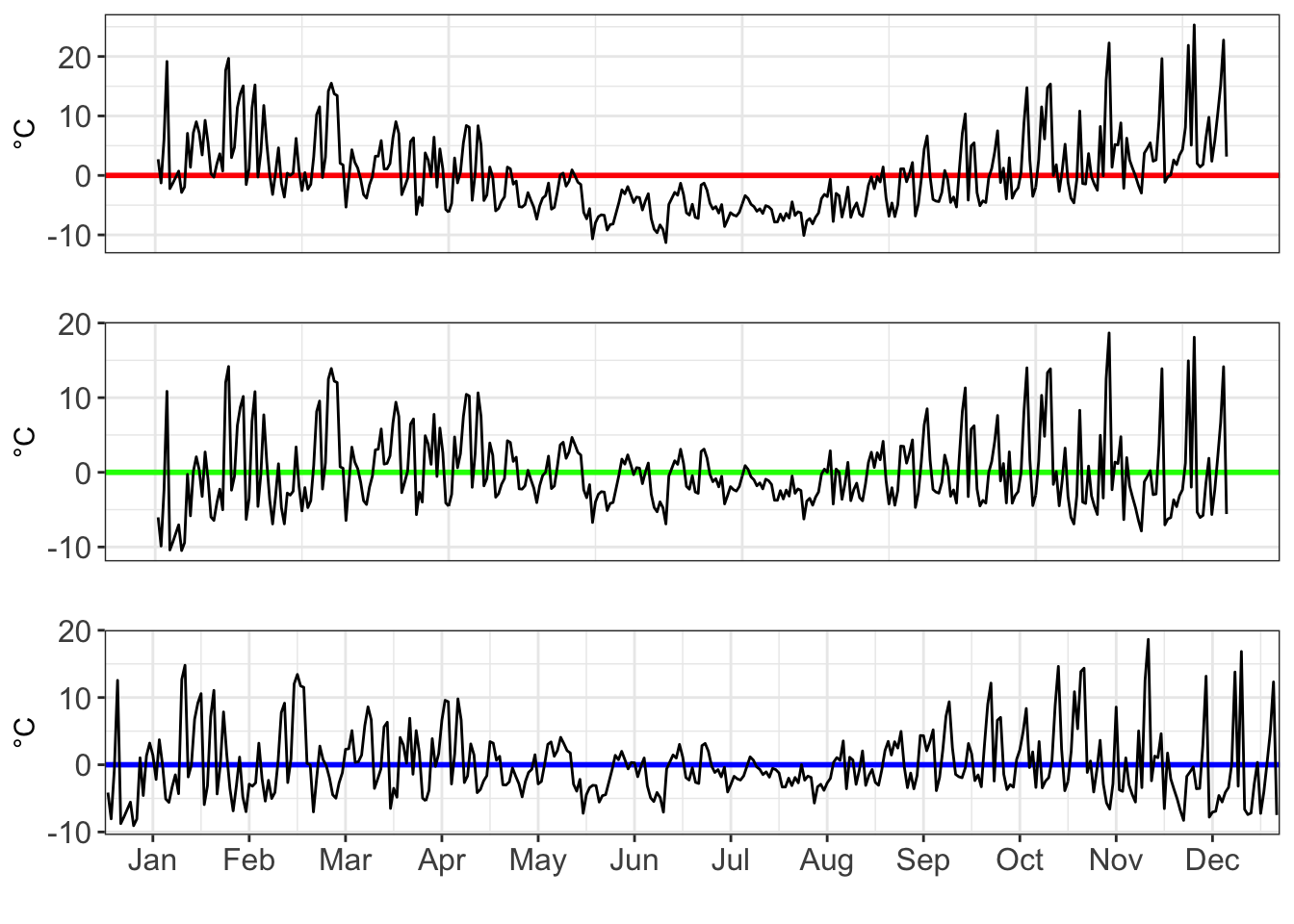

Just how variant are they? We can look at the residuals to find out. The residuals is the gap between the observed data point (i.e. the grey line) and our model.

#Get the residuals for poly1

residuals_poly1 <- MEL_weather_2019 %>%

add_residuals(poly1)

residuals_poly1_chart <-

ggplot(data=residuals_poly1,aes(x=Day_number, y=resid))+

geom_ref_line(h=0,colour="red", size=1)+

geom_line()+

xlab("")+

ylab("°C")+

theme_bw()+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=12))+

theme(axis.ticks.x=element_blank(),

axis.text.x=element_blank())

residuals_poly1_chart

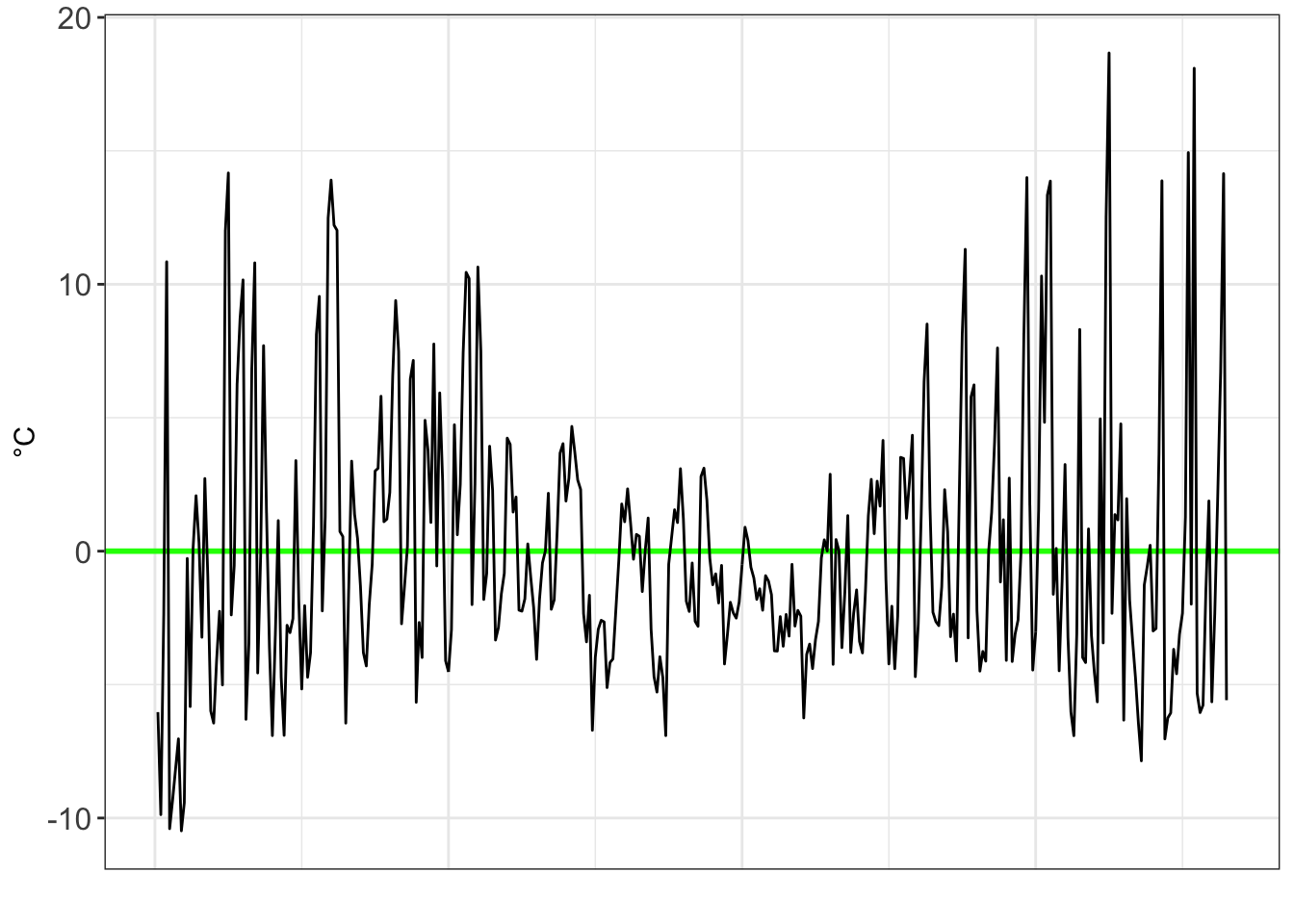

#Get the residuals for poly2

residuals_poly2 <- MEL_weather_2019%>%

add_residuals(poly2)

residuals_poly2_chart <- ggplot(data=residuals_poly2,aes(x=Day_number, y=resid))+

geom_ref_line(h=0,colour="green", size=1)+

geom_line()+

xlab("")+

ylab("°C")+

theme_bw()+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=12))+

theme(axis.ticks.x=element_blank(),

axis.text.x=element_blank())

residuals_poly2_chart

#Get the residuals for poly3

residuals_poly3 <- MEL_weather_2019 %>%

add_residuals(poly3)

residuals_poly3_chart <- ggplot(data=residuals_poly3,aes(x=Day_number, y=resid))+

geom_ref_line(h=0,colour="blue", size=1)+

geom_line()+

theme_bw()+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=12))+

scale_x_continuous(breaks=

c(15,45,75,105,135,165,195,225,255,285,315,345),

labels=c("Jan", "Feb", "Mar", "Apr", "May", "Jun", "Jul", "Aug", "Sep", "Oct", "Nov", "Dec"),

expand=c(0,0),

limits=c(0,366))+

xlab("")+

ylab("°C")

residuals_poly3_chart

three_charts_single_page <- plot_grid(

residuals_poly1_chart,

residuals_poly2_chart,

residuals_poly3_chart,

ncol=1,nrow=3,label_size=16)

three_charts_single_page

As we move from a linear, to a x², to a x³ model, we see the residuals decrease in volatility.