1.3 Extraneous variables and variation in the response

Other variables probably exist which are associated with changes in the value of the response variable; these are called extraneous variables.

All extraneous variables are, by definition, related to the response variable. An extraneous variable may or may not be associated with the explanatory variable as well. Extraneous variables may have other names too (Table 1.1), though these names are used inconsistently by researchers (Dunn et al. 2016).

![]()

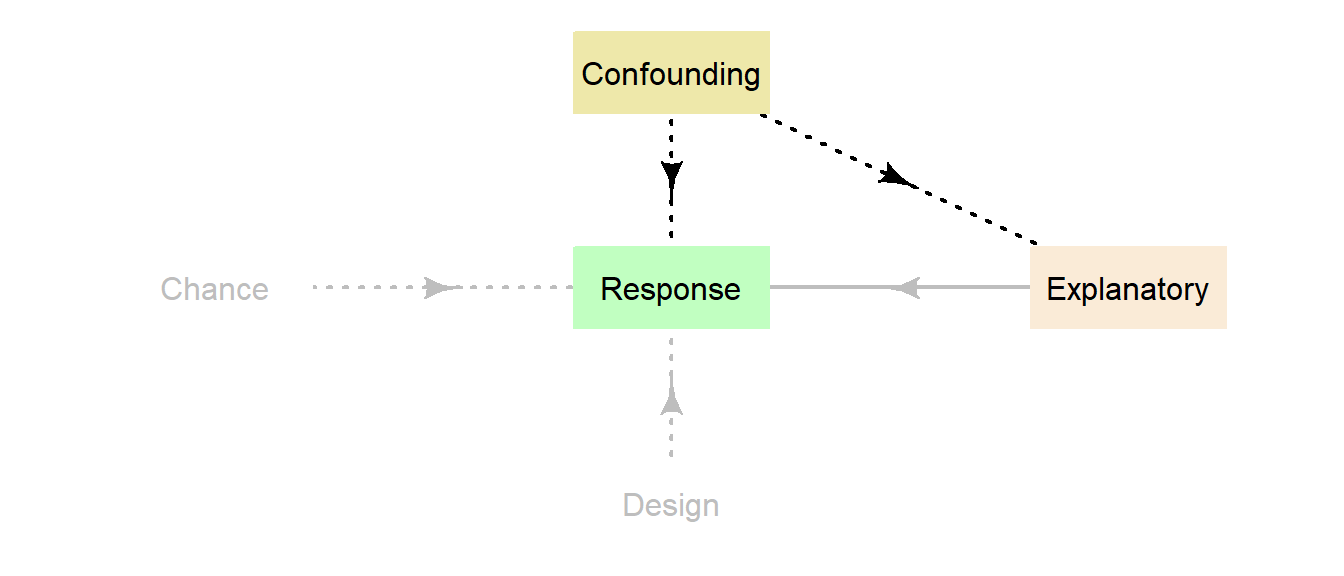

The problem with confounding is a relationship between the response and explanatory variables may be evident, but only because both of these variables are related to the confounding variable (Fig. 1.3).

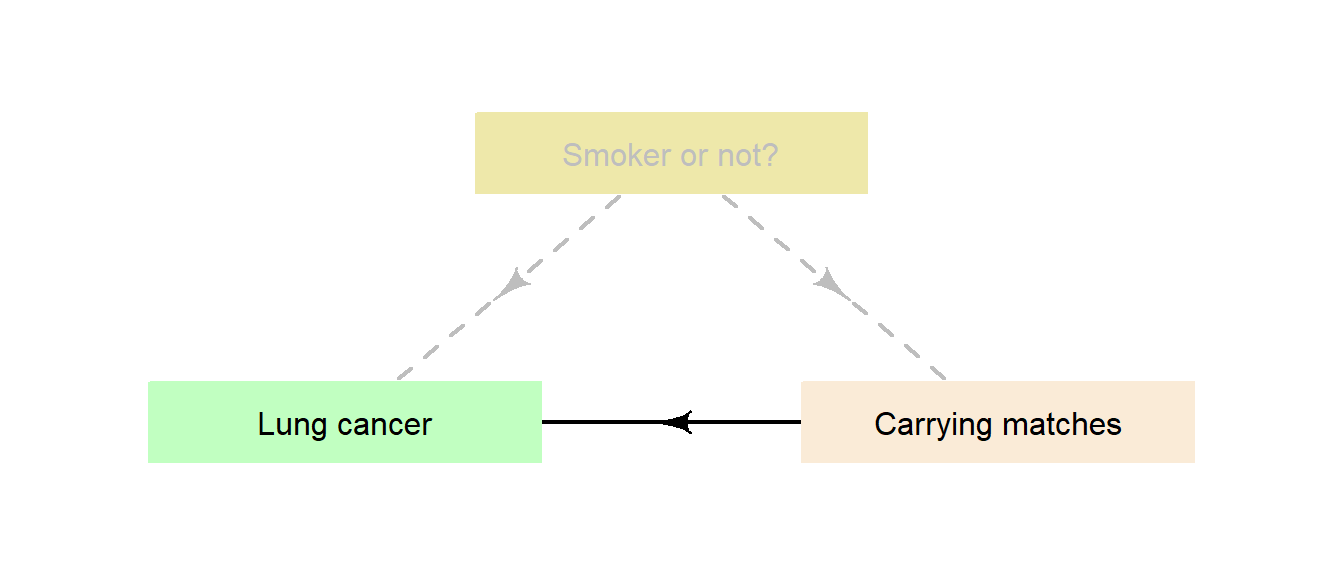

Example 1.3 (Confounding variables) A relationship exists between carrying cigarette lighters, and lung cancer: people who carry cigarette lighters are more likely to get lung cancer.

The only reason that this relationship exists is because of a confounding variable: whether or not the person is a smoker. A smoker is more likely to carry a cigarette lighter, and is also more likely to develop lung cancer.Managing confounding is very important, as confounding can completely change the relationship between the response and explanatory variables and hence can compromise internal validity.

Ways of managing confounding are discussed in the next topic.

Figure 1.3: Confounding variables are extraneous variables associated with the response and explanatory variables

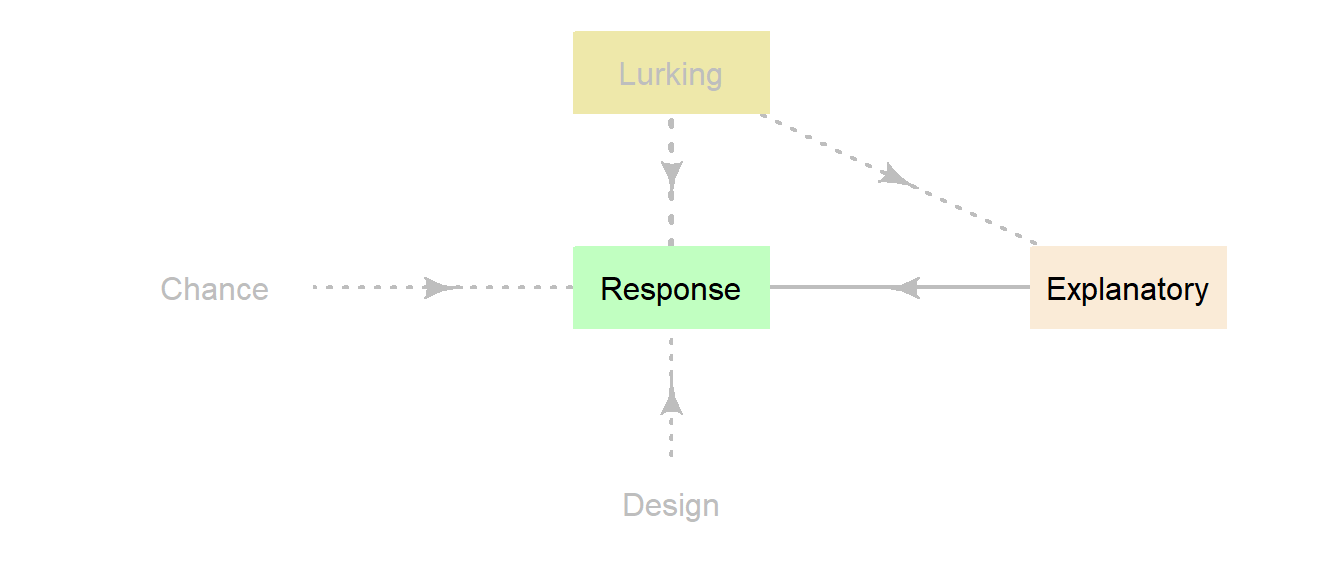

Sometimes confounding variables are not measured, assessed, described or recorded; these confounding variables are then called lurking variables (Fig. 1.4). Failure to acknowledge lurking variables can lead to wrong conclusions.

Figure 1.4: Lurking variables are associated with the response and explanatory variables, but are not recorded

Example 1.4 (Lurking variables) Consider the relationship between carrying cigarette lighters, and developing lung cancer (Example 1.3).

In this study, we could define:

- the response variable as "whether or not a person gets lung cancer"; and

- the explanatory variable as "whether or not a person carries a cigarette lighter".

Now consider the variable "whether or not a person is a smoker". This variable is associated with the response variable (people who smoke are more likely to get lung cancer than those who do not smoke) and with the explanatory variable (people who smoke are more likely to carry a cigarete lighter than those who do not smoke).

Hence, if that information was recorded by the researchers, it would be called a confounding variable.

In contrast, if it was not recorded by the researchers, it would be called a lurking variable (Fig. 1.5).

Now consider the variable "whether or not the person worked closely with someone who smoked". This variable is possibly associated with the response variable (someone who works closely with a smoker would be slightly more likely to get lung cancer ('passive smoking') than someone who does not (Taylor et al. 2001)), but is very unlikely to be associated with owning a cigarette lighter (whether or not someone owns a cigarette lighter probably doesn't depend on whether or not they work closely with a smoker).

Hence, if that information was recorded, it would be an extraneous variable (but not a confounding variable).

If that variable was not recorded, the variation it produces in the response variable would just end up as part of the chance variation.

Figure 1.5: An example of a lurking variable

To clarify (Table 1.1):

- Extraneous variables are all related to the response variable, by definition.

- Some extraneous variables are also called confounding variables: if they are also related to the explanatory variable.

- Some confounding variables are also called lurking variables: if they are not measured, assessed, described or recorded.

Some unknown extraneous variables will be associated with the response variable only, and so become part of variation due to chance (i.e., unexplained). These terms are not always used consistently by all researchers (Flanagan-Hyde 2005).

| Type | Associated with response | Associated with response and explanatory |

|---|---|---|

| Measured or observed | No special name: extraneous | Confounding (not lurking) |

| Not measured or observed | Becomes part of 'chance' | Lurking |

To avoid lurking variables, researchers generally collect lots of information about the individuals in the study (such as age and sex if the study involves people) and circumstances of the study (such as the temperature) that may be relevant, in case they are confounding variables.