8 Writing, argumentation, presentation, and (Economic) logic: Being clear and making sense

… it is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing. – The Tragedy of Macbeth, W. Shakespeare, Act 5 Scene 5.

8.1 What is this and why would anyone read it?

What is this?16

This article generally, gift economy, modern and pre-modern, mainstream, and behavioral economics point of view, considered a gift. I selected literature survey focused on six key points of the proposal:

- gift exchange transaction easy to distinguish the economy, faced not reliable 2. Buying equipment, collection, your business can not afford.

- Some donors experience or gift retains control over the stock of the public. Four. Woe to such disgusting behavior problems as a gift, think about a balanced performance “inadequate” deadweight loss of gift giving can be ignored.

V. International (anonymous) signal identification and quality of the whole group can.

Can you make sense out of this text? Would you like to read something like this?

A reader cannot guess what is in your head. He or she can only interpret what is written down. It’s not enough for you as the writer to have great ideas and understand things well; you need to convey this to the reader. If the person who is marking your work cannot understand what you mean in a section, they may just skip this section.

8.2 Writing well: Clarity

Your writing must be understood by others. This sounds obvious, but it is not always easy to do. As McCloskey (2000) notes, try to write not only “so that the reader can understand but so that he cannot possibly misunderstand.”

[not] merely so hat the reader can understand but so that he cannot possibly misunderstand.

Write so that the reader’s brain does not freeze up. You want the reader to come along with you for the journey. Do a grammar and spelling check and use online tools like Grammarly. After you have completed a first draft of your essay, set it aside for a while – a few hours or overnight. Then read it again and make it better. Before you submit it, get feedback from someone else to make sure it is readable.

Make sure your word processor is set to language=English. Otherwise it may get confused and not notice mistakes at all!

How to write clearly - key rules:17

Sentence structure: Simple, short sentences with few clauses are usually easier to follow than long-winded excursions with many clauses, like this marathon of a convoluted sentence in which I wander around for a while and obscure the main idea, making it more and more confusing, which is exactly the point I’m trying to make—see what I’m doing? Delete words that add little or no extra meaning and skip unnecessary, superfluous, insignificant, unwanted padding – like this.

Keep your sentences lean and clean.

Diction (word choice): Prefer short words to long ones. Whenever possible, use everyday English rather than foreign words, scientific terminology or jargon. Sometimes you have to use technical language, but avoid it when you have a choice. Because certain words have a particular technical meaning in Economics (or in related fields such as Statistics) and it is important to get these right.When you need to be precise, use the language of Economics.

Active vs. Passive Voice: Active verbs add life to your sentence. The opposite effect is achieved by using the passive voice. (See?) And whether passive or active, be clear who did what to whom.

Tone: Make your language as clear and understandable as possible, while sounding professional and academic(but not pedantic or pretentious).

You need to strike a balance between writing in your own voice and using the standards of the profession. You want to hear your own voice in your writing, but you probably don’t want to write as you would speak to your mates over several pints.

Audience: As you write, think about who the intended audience is. Write as if you were speaking in a public seminar or debate in front of a highly-educated group (with some Economics training).

8.3 General tips (especially for Economics)

The tips in this subsection are not Economics-specific, but they are particular relevant for the formats and approaches in our field.

Format. Make your paper look presentable by following a standard format.

Focus. Ask a question and try to answer it.18 Do not stray from your topic.

Make your paper presentable and standard in format: Find examples of well-written papers and their correct formats and make your paper look like them in its style and format.

Be focused. Your dissertation should ask a question and try to answer it. Do not stray from this.

Write about Economics. Your dissertation or essay should demonstrate some of what you have learned in your modules.

Ask yourself: does my work contain substantial Economic content?19

Show understanding, but don’t “show off” pointlessly. Make it clear that you understand your topic, but don’t expand on concepts that are irrelevant to your central question.

Modesty is a good policy. Never say “never” and always avoid “always”, or at the least handle those absolutes with care. Overusing such words is an invitation for critics to hold you to your own impossible standard.

Little in empirical Economics can be conclusively demonstrated.20 Don’t claim to have definitively answered an earth-shattering question. If you are doing empirical work your goal is to present a small but credible piece of evidence that answers an interesting question. If you’re doing a theoretical paper, consider applying (and extending) an existing model to a new context. If your paper is a literature survey, try to bring a new perspective or insight into your overview of the existing work.

Honesty is the best policy. It protects you from being accused of plagiarism, and allows you to legitimately claim credit for your own work. Be sure to differentiate what you have done from the work of others. Explain what your contribution is and fully reference the work of those whom you mention and cite.

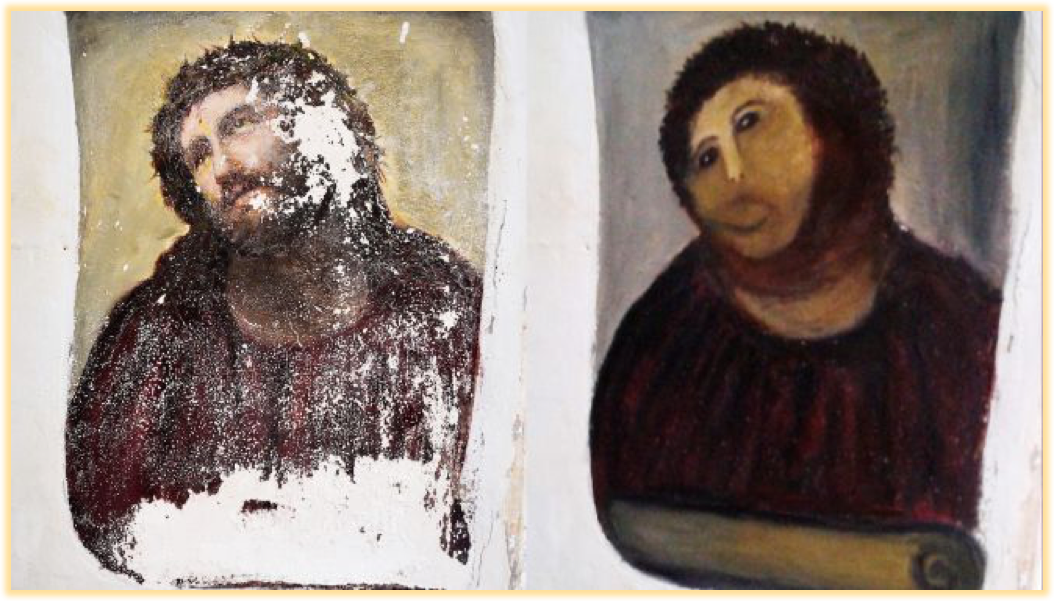

8.4 Aspirations and Reality; learning by (counter-) example

To ascend to the heights of precise, elegant, powerful, and convincing prose, you must read, write, and critique for many years. You can learn a lot by finding some Economics articles that are widely acknowledged to be examples of great writing, and carefully dissecting these to understand what makes them work.

8.5 Writing in a professional style

Tone

Make your language as clear and understandable as possible, while sounding professional and academic (but not too academic). This is called the ‘tone’ or the ‘voice’ of your writing. You need to strike a balance between writing ‘in your own voice’ and writing using the standards of the profession. You want to hear your own voice in your writing, but you probably don’t want to write as you would speak to your mates over several pints. As you write, think about who the intended audience is. Perhaps write as you would like to speak in a public seminar or debate. However, this doesn’t mean adding in jargon and fancy phrase constructions – that is a waste of time.

Terminology

You need to use the language of Economics. Certain words have a particular technical meaning in Economics (or in related fields such as Statistics) and it’s important to get these right.

8.6 Writing: Clarity, style, tone, and correct terminology. Common problems.

To ascend to the heights of precise, elegant, powerful, and convincing prose, you must read, write, and critique for many years. You can learn a lot by finding some Economics articles that are widely acknowledged to be examples of great writing, and carefully dissecting these to understand what makes them work.

For now, however, I want to help you avoid the major problems and pitfalls I have seen in student essays.

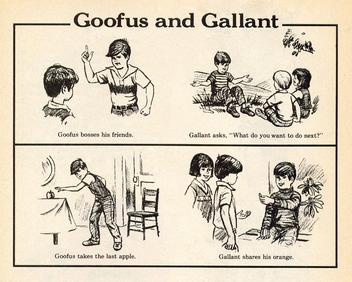

Don’t be a Goofus. Strive to be like Gallant.

In the next sections I give some specific advice on things to definitely do and not do, as well as specific examples of (note color-coding)21

Goofae: Examples of things to endeavour to avoid doing,

and

Gallants: Examples of good practice.

Content and narrative

Students often ‘discuss the wrong things’ and describe them in the wrong way. This detracts from the argument, and can make the paper confusing, disjointed, and a pain to read.

Three of the most common sins are ‘Sins of excess’:

boilerplate language,

excessive detail, and

repetition.

“Boilerplate” and generic and obvious discussion: “Boilerplate” language is what I call the pointless, obvious and dull language resembling the text written on a plate of one’s boiler, or the tag on one’s mattress. Leave it out.

There is no doubt whatsoever that education is the engine that drives our population further. Knowledge is poetically described by a number of philosophers as a very powerful tool, which is essential to humankind in order to grow.

This may be conventional wisdom, but it doesn’t belong in a research paper.

Labour market performance has been widely investigated by economists. Determinants of labour market performance have been comprehensively researched as economists attempt to identify measures and adjust fiscal policy and regulations in order to strengthen labour market performance for the benefit of the economy.

This takes a long time to say something quite obvious: economists are interested in the labour market. But anyone reading this essay should already know this. If an introductory sentence is needed here, make it short and sweet. E.g., “I present a brief survey of the extensive literature on labour market performance.”

Another example …

In an increasingly complex international economy, a vast array of possible policy strategies and hundreds of different governmental structures, politicians are faced with the challenge of maintaining public interest while providing a suitable environment for economic stability and growth . … I will attempt to show a convergence in existing theory on matters of critical importance to international development, while providing examples of large-scale failures to uphold the public interest.

Too much detail

Don’t give irrelevant detail and ‘lose the forest for the trees’. This makes the paper too long and hard to follow.

In terms of higher education, there are 19 Sub-Degree institutions, and 2 public institutions. There are 15 degree-awarding higher education institutions, 7 of them are self-funded institutions including two private universities such as Open University of Atlantis and Atlantis City University, publicly funded institution such as the Atlantis Academy for Performing Arts (HKAPA) and some college such as John McEnroe Management College and Boris Becker College of Higher Education. The remaining 8 of them are University Committee UC) funded institutions, including 6 universities and 1 auto repair institution). The seven Universities are City University of Atlantis (CityU), Atlantis Jesuit University, Lesbos University (LU), The Atlantic University (PolyU) and some are relatively famous which are The University of Atlantia, The French University of Atlantis, and The Atlantian University of Science and Technology (AUST). The remaining teacher training institution is The Atlantis Institute of Miseducation (AIMe).

Too much! Is anything gained by this long list?

Better:

There are more than 21 institutions of higher education, covering academic and vocational subjects and teacher training in Atlantis.

The focus of my dissertation is the effect of exchange rate variability on the trade balances between OECD countries namely, Austria, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UK and USA.

(At most, put a footnote here listing these countries, if you feel the list is important.)

Repetition

Always avoid unnecessary repetition.

Example:

Corruption in the government sector fits into the classical association with the principal-agent problem in the sense that there is interest and information asymmetry between the agent – the corrupt government official, who is more interested in personal pursuits – and the principal (typically represented by citizens) who are focused on general public interest. In this context, corrupt government officials represent the agents who pursue individual interests…

Here the last sentence is redundant, since it just repeats the point made in the first sentence, i.e. that the corrupt government official represents the ‘agent’ in the relevant principal-agent model.

Grammar and sentence construction

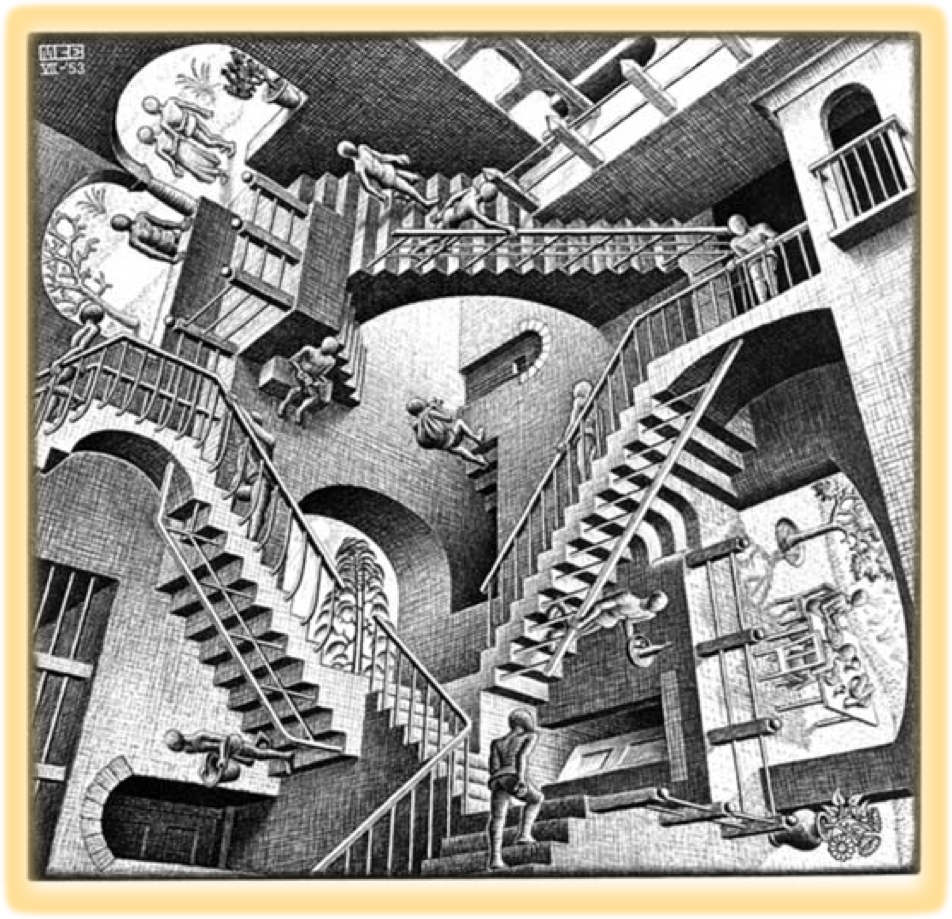

Obviously, poor grammar and convoluted sentences will make your work hard to read. If the logic is hard to follow, if it’s unclear to what you are referring, or if your sentences aren’t actually sentences, you will lose your reader. Spare your reader a trip to…

Figure 8.1: the land of confusion

One of the most common culprits is the use of a pronoun when the subject to which it refers is ambiguous.

Subject of a pronoun: When you use “it” or “he” or “the argument” or “this” (etc.), be sure to let the reader know the antecedent. In other words, to what does the pronoun refer?

A good theatre critic is one who recognizes the quality of acting, production and other such aspects, whereas a realistic critic can judge how a play will be received by the general public. If this is the case, then it can be used in conjunction with Smith and Jones’s influence and prediction idea.

“If this is the case, then it…”: to what idea does the pronoun, “it”, refer? The student might have meant that:

There are two types of critics.

Some (or all) critics recognise quality.

Some (or all) critics judge how well a film will be received.

the idea that there are two types of critics,

the idea that some (or all) critics recognise quality

or the idea that some (or all) critics judge how well a film will be received.

About whom are we talking?

Another common way to goof things up is with a …

“Run on” sentence… This kind of sentence strings along too many phrases and clauses.

As they became aware of the fact that there was a, potentially very strong, connection between the two, and how a child’s outcomes and ability to contribute to the labour force (once fully developed) is determined by his or her cognitive development from a very early age, with a lack of parental involvement potentially having a highly adverse effect on this, the need to answer this question became much more apparent and essential.

This text should be broken up into several sentences. Too many ideas are packed into one.

On the other hand, don’t cut things too short. A sentence needs both a subject and a verb.

Fragment: a group of words that resemble a sentence, but lack either a subject or a verb.

Some organizations also find it as a good way to keep their employees within the organization. Which build up a high level of competence (Smith et al, 1776).

*The second phrase is a sentence fragment. Every sentence needs to have a subject and a verb (and sometimes an object).22

Tone

“Flowery” language

Don’t use big words and complicated constructions unless necessary. You don’t need to be fancy. Write simply and concisely.

This indissoluble connection between these two benefactors has been theorized into the substitution phenomenon.

The words “indissoluble” and “phenomenon” and “benefactors” are probably not needed here. “Has been theorized into” is an awkward construction. I’m not sure what this sentence was intended to mean. Probably something like ‘these two factors are both determinants of the substitution effect.’

Informality

Use language that is polished, scientific and professional. Do not use slang. You want to be clear, but you aint ‘avin a laff over a pint at the pub.

The Irish Parliament proposed to cut spending on these organisations and has axed 102 regional quangos…

Avoid the use of slang and highly informal words like “axed”. Instead, say ‘de-funded’. Technical terms unfamiliar to your reader, like “Quangos”, should probably be defined when they are first mentioned.

On top of this, I have two of my own theories that I will be testing.

Inserting yourself and discussing your process

The reader knows you are the writer. No need to point that out. (Unless necessary, as in the example above, where the writer points out that the additional hypotheses are her own.)

From my research I have learned that the studies that support the proposals made by Ofsted have been extremely costly.

Don’t write “my research” or “I have learned” and don’t call attention to the process of research and writing, unless it is necessary to explain your findings.

There are other problem here: it is unclear what is ‘extremely costly’; the studies or the proposals. Furthermore ‘studies that support’ is a confusing idea; do the studies favour the Ofsted proposal? The studies should be specifically cited (and possibly explained in more detail). And what is ‘extremely costly’; that’s a subjective judgement and a vague statement.

Better (if this is what was intended):

Several studies (Smith et al, 2017; Jones and Ali, 2018; Chang, 2018) make long-range projections following the Johnson (1999) cost-accounting method. Each of these studies independently finds that Ofsted’s baseline proposal will cost over £12 billion per year over the next ten years.

Excessive formality and ‘academese’

Don’t go too far in the other direction! Avoid academic jargon, ially the tendency to turn common words into fancy-sounding nouns.

An example from outside Economics:

Structuring meaning multidimensionally is co-creating reality through the languaging of valuing and imaging.

“Languaging of valuing”? I have no idea what this means. Aren’t you glad you are studying Economics?

Closely related to ‘tone’ is the issue of how carefully and modestly we state the claims that we make, and what we are asking the reader to do with these.

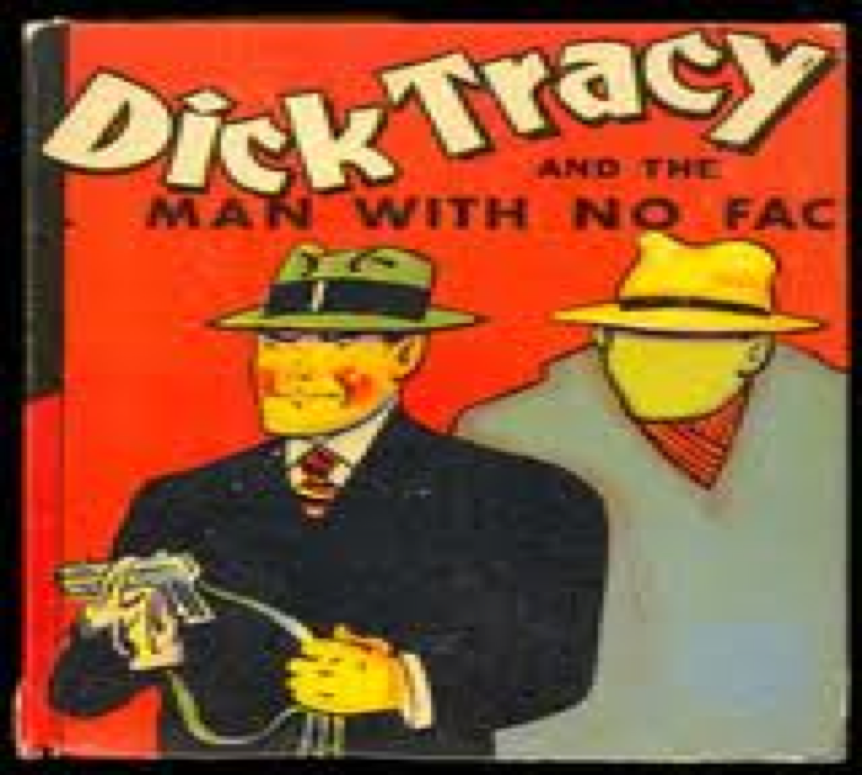

Proclamations and commands

Closely related to ‘tone’ is the issue of how carefully and modestly we state the claims that we make, and what we are asking the reader to do with these.

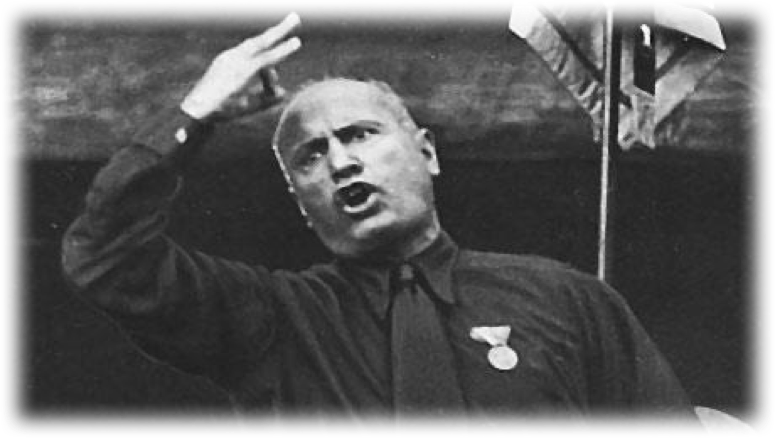

It didn’t work out well for this guy.

The textile products must pass a rigorous inspection process which may increase trade costs. Mexico’s producers need to respond to this by cutting costs and increasing quality in order to stay competitive.

Must the textiles pass a rigorous inspection by law? If that’s true, it is fine to say so. Do Mexico’s producers ‘need to’ cut costs and increase quality, or is that the writer’s opinion? Your research is not meant to dictate. You need to be objective and weigh evidence carefully.

Word choice (aka ‘diction’) and terminology

Be careful when you choose words, both technical and commonplace. Using the wrong word can make things very confusing.

A study carried out by Smith (1975) looked into the effects of business unit size on business unit R&D intensity, using data which were composed by the US Federal Trade Commission.

The student probably meant that the data were collected by the US FTC, but it is not clear. “Composed” is a confusing word choice here.

Terminology

When you use technical terms specific to Economics (or Statistics or other fields), be sure you are using them correctly.

This section focuses on looking for trends between various papers and pieces of published literature, analysing them in terms of how relevant they are today, how knowledge of the field has evolved and whether the date they were released indicates a direct correlation of their relevance in today’s society.

The word “correlation” is inappropriate here. A correlation is a statistical measure. Note also that the above is fairly obvious and is stated in too many words.

Better:

In this section I review the published evidence. I discuss how the field has evolved and consider whether older work is less relevant to the contemporary situation.

Another example:

Johnson et al. (2000) provide an analytical framework that sheds substantial doubt on that belief. When trying to obtain a correlation between institutional efficiency and wealth per capita, they are left with largely inconclusive results.”

They are not trying to “obtain a correlation”; they are trying to measure the relationship and test hypotheses.

Better:

… They empirically examine the relationship between institutional efficiency and wealth per capita; these results are largely inconclusive.

Schumpeter assumed that there will always be a stronger incentive for a monopolist to be innovative than a competitive firm.

Schumpeter is not assuming (an assumption is a premise for an argument), this is his theory of innovation. Much of his work is devoted to justifying this theory.

Better: “Schumpter argues that …”

Linking words and transitions

Your arguments must, above all, be logical. (See ‘logic and argumentation’.) The grammar of your sentences implies a certain logic, particularly through the use of what I will call ‘linking words’.

Do not use transitions and linking words unless the ‘logical conditions hold’ for them to make sense (see examples below). Otherwise you will confuse the reader.

Words like “therefore” or “henceforth” are used to mean that the previously stated idea implies the following one.

Through welfare programmes, governments can reduce inequality in society. Therefore, countries that do not have an efficient welfare state create an impediment to development and sustainable economic growth.

The first sentence highlights a link between a welfare system and inequality. So, after “therefore”, we expect something like “countries that do not have an efficient system of welfare benefits are more likely to experience high inequality”. Logic dictates that the second sentence should be about inequality not about growth.

Words like “although,” “however,” “nonetheless,” and “in contrast to” imply that the idea you are about to introduce is surprising in light of the idea that precedes it.

I find trade a useful variable to analyse the relationship between FDI and economic growth. Although there are countries that are not totally open to trade, such as North Korea, countries with openness to trade have higher growth rates than countries with a more restrictive trade law.

The “although” here does not make sense. The fact that North Korea is a closed economy is not in contrast to the idea that openness leads to growth. North Korea is not known to have experienced strong growth.

On the one hand, the import penetration ratio has risen rapidly since the 1970s. On the other hand, the manufacturing sector has shrunk from roughly 75% of the Atlantean GDP to less than 30% in just 60 years.

This is not ‘on the other hand’; these facts argue in the same direction.

8.7 Revising, rewriting and proofreading

“Reading your own writing cold, a week after drafting it, will show you places where even you cannot follow the sense with ease.” – McCloskey

Never turn in a paper for preliminary feedback nor for your final submission without first doing a spelling and grammar check, as well as looking over the entire paper one last time for random errors.

For example, in MS Word: Select your entire document, use the “Tools” menu to make sure your entire document is set to language: English. Use –“Tools” –“Spelling and grammar check” (instructions as of 2017)

8.8 Sections to be added:

Presenting an argument

Polishing your paper and making it look professional

Logic and rigour

Statistical and econometric logic and rigour; stating your results (and others’)

For example, if you are using an instrumental variables approach, what is your instrument and how do you justify it? State this early in your paper and prominently.

Correct economics; using what have learned in your coursework

How to write if you have difficulty writing in English

David Reinstein, The Economics of the Gift, translated from English to Chinese to French to Urdu and back to English by Google Translate.↩

This is inspired in part by The Economist online (Prospero blog, “Johnson: Those six little rules”, July 29, 2013). "Many years ago George Orwell famously proposed six rules for writing (“Politics and the English Language”, 1946). While much revered, Orwell’s rules are now regarded as overly strict – even Orwell failed to comply on occasion .’’*↩

Your dissertation/project may ask a single question or a small set of inter-related questions, but keep things focused!↩

If not, you have probably gone off-piste. If you are putting in a lot of depth and detail into something and you are not sure if it is Economics, you may want to consult your advisor about this. It’s OK to have substantial background content, e.g., descriptions of an industry or an institution if it is highly relevant to your Economics question. But don’t go into excessive detail on this, and make sure you also have the Economics content.↩

In empirical Economics where we make and test claims about the real world based on evidence, which is expressed in the language of statistics. In Economic theory we can prove theorems, essentially the logic of ‘if-then’ statements… ‘if one assumes the following preferences, the following choice is optimising’, etc. However, here the realism of the assumptions is always in question; as caricatured in this Twitter meme↩

In the ‘thou shalt not’ section I give further examples and discussion, covering topics referenced throughout this book.↩

Sentence fragments are sometimes acceptable in bullet points, e.g., as part of slide presentations.↩