Chapter 13 RAxML

13.1 Objectives

By the end of this week, you will:

- Have RAxML installed

- Be able to do an analysis with likelihood with various models

- Understand partitioning

- Be able to use a variety of character types

RAxML (Stamatakis, 2014) is a very popular program for inferring phylogenies using likelihood, though there are many others. It is notable for being able to infer trees for tens of thousands of species or more. New versions can use DNA, amino acid, SNP, and/or morphological characters.

13.2 Install RAxML

To begin, install RAxML. Follow the instructions in Step 1 of http://sco.h-its.org/exelixis/web/software/raxml/hands_on.html. For the fewest issues, just do make -f Makefile.gcc on the command line (not in R) to compile the basic vanilla version. For actual work, you’ll likely find the versions with SSE3 and/or PTHREADS will work faster. On a Mac (Linux is similar; RAxML has binaries), the easiest way to get use this would be:

git clone git@github.com:stamatak/standard-RAxML.git

cd standard-RAxML

make -f Makefile.gccIf compiling went correctly, you should see a line like

gcc -o raxmlHPC axml.o optimizeModel.o multiple.o searchAlgo.o topologies.o parsePartitions.o treeIO.o models.o bipartitionList.o rapidBootstrap.o evaluatePartialGenericSpecial.o evaluateGenericSpecial.o newviewGenericSpecial.o makenewzGenericSpecial.o classify.o fastDNAparsimony.o fastSearch.o leaveDropping.o rmqs.o rogueEPA.o ancestralStates.o mem_alloc.o eigen.o -lmNow you need to put the program in a path. This is where your computer looks for programs to run. If you type a program name, like ls or raxmlHPC, your computer checks the folders indicated in the path for a program of this name; when it finds one, it runs that. You can see your path by typing echo $PATH. If you want to run a program, like the newly compiled raxmlHPC, you have two options: you can specify where it is each time you want to run it, or you can put it in a folder in your existing path. The former becomes a pain, so I’d recommend the latter. /usr/bin is in your path, but this is reserved for programs your computer needs to run – don’t mess with it. I’d suggest putting it in /usr/local/bin. To do this, type

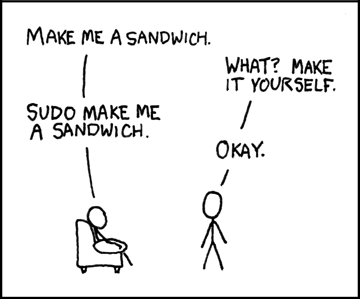

sudo cp raxmlHPC /usr/local/bin/raxmlHPCsudo means superuser do. It’s a very powerful command. Generally, typing on the command line you can delete files that are important to you, but it’s hard to utterly destroy your computer; with superuser abilities, you could delete key files.

Sudo sandwich from xkcd

Ok, so we now have RAxML installed. To run it, you could use the very handy ips package to call it from R, but it doesn’t have an interface to all of the relevant commands. Instead, we’re going to just create some commands to run ourselves.

First, we need sample data sets. We will be using ones, modified somewhat, from this tutorial. The original files are here but the modified ones are in the repository for this PhyloMeth exercise in the /inst/extdata folder.

Until now, we’ve seen NEXUS files, which can include data blocks. RAxML uses Phylip-formatted files instead, which are simpler: a line that has the number of taxa and the number of sites, followed by one line per taxon with the taxon name, a space, and then the characters (though there could be interleaving).

13.3 Morphology search

First, we are going to examine morphology using likelihood. While morphology is typically analyzed with parsimony, there are models for morphology (i.e., Lewis 2001) and research suggests (Wright & Hillis, 2014) that such models outperform parsimony for morphology, in addition to being less prone (in theory) to long branch attraction (Felsenstein 1978). Therefore, absent strongly held concerns rooted in an epistemological paradigm, it seems prudent to use a parametric model for morphology (note this can be done in likelihood or Bayesian contexts).

Get the exercise and complete the InferMorphologyTree_exercise function in exercise.R. Also, look at the data in a text editor to get a sense of the structure. Which taxa are going to be lumped into clades, do you think? Some important things to note:

- Morphology (as well as some other data, such as SNPs) often includes only variable sites. This can cause a problem if not accounted for (it looks like all sites are evolving really fast, because the slow ones are ignored). There are corrections for this, three of which are implemented in RAxML.

- RAxML creates a starting tree, then does a parsimony optimization, then likelihood. This is not a full parsimony search, though.

- Remember that for nearly all tree searches, heuristic methods are used. That means that you are not guaranteed to get the best tree; given the size of tree space, one could almost say you’re guaranteed not to find the best tree.

- Computers are great at being logical. The downside is that they are terrible at being random. They often use the current time as a “seed” to get a pseudorandom number. You could think of it (this is more of an analogy than a description) as if the computer had a long table of stored “random” numbers, and that it started using numbers at the row corresponding to the number of seconds elapsed between the current time and some fixed date in the past. If you start two runs at different times, they’ll have different numbers, but if you start them at the same time, they’ll have the same ones. For tree search, there are often random moves: which branch is broken off and moved somewhere else. If you start two searches at the same time, thinking you’re doing two independent searches, they’ll perform exactly the same, despite the “randomness”. RAxML asks users to supply a random number seed to it. If you use the same one across runs, they’ll be exactly the same.

13.4 DNA

Most phylogenetic analyses for extant organisms use sequence data. This is often presented as DNA, though sometimes the data are translated to amino acids instead. Usually sequences from multiple genes are concatenated. There are a wide range of models available for sequence evolution. For DNA, the most popular remains general time reversible (GTR): a model that allows for a different transition rate between every pair of nucleotides, subject to the constraint that the rate from nucleotide i to j is the same as the rate from j to i. Different sites evolve at different rates (think of the sites coding for the active site of an enzyme versus those in an intron that has little to no functional purpose). One way to model this heterogeneity is with a gamma distribution: the likelihood is evaluated using several different rates for that site (Yang 1995). One can also apply partitions: allow different sections of the data to have different rates. This is commonly done to allow first, second, and third codon positions to have different rates, or to allow different genes to have different models of evolution. This can offer dramatic improvements in the fit of a model to the data; it is especially important when dealing with gappy data, such as cases where one gene is present for all taxa but another gene has ben sampled for only a subset of taxa.

Do InferDNATreeWithBootstrappingAndPartitions_exercise() in the homework. Once this is done, install this homework library into R. From the folder containing the homework:

R CMD INSTALL LikelihoodTreesThen, in R:

library(PhyloMethLikelihoodTrees)

results <- InferDNATreeWithBootstrappingAndPartitions_exercise()Though you may have to include other arguments (especially input.path).

You can plot your final tree:

library(ape)

plot.phylo(results$ml.with.bs.tree, show.node.label=TRUE)This shows the branch lengths of the best ML tree and the bootstrap proportions. This is from a non-parametric bootstrap (Felsenstein 1985): the columns of data are sampled with replacement and then a tree search is redone. The more times a bipartition (an edge) on a tree is recovered, the more confidence we have in it (but this is not the same as the probability of it being true). Note one common error: the numbers reported, and in this case shown at nodes, are not properties of a node or a clade: they are bipartitions: taxa A, C, E fall attach (perhaps through other nodes) to one end of an edge, and taxa B, D, E, F, G, H are attached to the other end.