Chapter 5 Part V

5.1 Definitions

Q: what do the words: [new, group, world, and servers] mean when they are put together in a phrase. What is new? What is group? What is world? What is servers?

A: Sure, I can define these words for you:

New: This adjective refers to something that has not been seen, used, or experienced before. It can also refer to something that is different from the old or previous.

Group: This noun refers to a number of people or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

World: This noun could mean the earth, together with all of its countries, peoples, and natural features. It can also refer to a particular region or group of countries, or all that relates to the experiences, life, and existence of people.

Servers: In the context of technology, servers are systems (which could be computer hardware or software) that manage network resources. They are often used to host websites, store data, and provide various services to connected clients.

Now, if you put these words together into a phrase like “new group world servers,” without further context, it’s hard to interpret its exact meaning. However, it could potentially refer to the launch or creation of new servers by a group aimed at serving a global audience. The specific meaning would largely depend on the context in which the phrase is being used.

Q: what do the words: [new, group, world, and (human) servers] mean when they are put together in a phrase. What is new? What is group? What is world? What is (human) servers?

A: Sure, I can define these words for you:

New: This adjective refers to something that has not been seen, used, or experienced before. It can also refer to something that is different from the old or previous.

Group: This noun refers to a number of people or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

World: This noun could mean the earth, together with all of its countries, peoples, and natural features. It can also refer to a particular region or group of countries, or all that relates to the experiences, life, and existence of people.

(Human) Servers: In this context, “servers” might refer to people serving or providing a service, such as waitstaff in a restaurant or volunteers in a community service context. When prefixed with “human”, it emphasizes that these servers are people, not machines or software.

If you put these words together into a phrase like “new group world (human) servers,” it could potentially refer to a new global group of people who are serving others in some capacity. The specific meaning would largely depend on the context in which the phrase is being used.

5.2 New Group of World Servers (NGWS)

Q: Within this context, what would the name: “New Group of World Servers” mean?

A: In the spirit of Hemingway’s clear and unadorned prose, let’s delve into the meaning of “New Group of World Servers”.

This phrase suggests a modern collective of individuals, united across geographical boundaries, whose primary purpose is to serve. Their service isn’t restricted to a local community or a single country; instead, it’s global. They are not just servers, but a new group of servers, implying that they are either replacing an old group, introducing new methods, or addressing new challenges.

The word “world” in their title suggests they operate on a global scale, engaging with issues that transcend national borders. It might mean they are a diverse group, bringing together varied perspectives from different cultures, backgrounds, and experiences.

The term “servers” indicates that their function is to serve. In what capacity, though, the name does not specify. They could be serving knowledge, aid, resources, policy advice, or any number of things. Given the global nature of their work, it’s probable that their service is intended to benefit humanity as a whole.

To sum up, this new group is a globally focused, forward-thinking collective dedicated to serving on a worldwide scale. They are a symbol of progress, unity, and altruism in a world often divided by borders and differences. Their mission and methods might be innovative, reflecting the “new” in their name, and their impact is likely far-reaching.

Q: Does such a group exist?

A: The phrase “New Group of World Servers” is indeed associated with an existing concept. It was first introduced by Alice Bailey, a writer of more than twenty-four books on theosophical subjects, and the co-founder of Lucis Trust, formerly known as Lucifer Publishing Company.

The New Group of World Servers is described as a group of people who are dedicated to service to humanity, driven by a spiritual orientation. Their role, according to Bailey, is to educate the public in the principles that underlie right human relations and goodwill. They are not an organized group in the traditional sense with membership or a specific leader, but rather individuals scattered all over the world, working in various fields, united by their shared vision of a better world.

However, this group’s existence is largely conceptual and spiritual, rather than physical or formal. It’s more of a collective consciousness or a shared commitment among like-minded individuals across the globe.

On a broader note, the existence of groups generally requires a shared identity or purpose among its members. This can be seen in the various examples from the search results, such as mathematical groups in group theory, social groups in sociology, and interest groups in politics. Each of these groups exists because their members share a common interest or identity.

Q: Can you provide examples of instances in history when an invention, a creation, a new idea, has found expression among different individuals who can claim authorship without implying plagiarism because they were physically separate, didn’t know each other, and didn’t communicate, directly or indirectly with each other?

A:Indeed, the annals of history are replete with instances of simultaneous discovery or invention. This phenomenon underscores the notion that human progress often follows parallel lines, with different individuals arriving at similar conclusions independently. Here are some examples:

Calculus: As you mentioned, both Sir Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz developed the foundations of calculus independently during the 17th century. This led to a bitter dispute over who was the original inventor, now known as the Newton-Leibniz controversy.

The Telephone: Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray both filed patents for the telephone on the same day in 1876. Bell’s patent was granted, but the similarities between their designs led to years of litigation.

The Lightbulb: Although Thomas Edison is most commonly credited with the invention of the practical lightbulb, several inventors, including Sir Hiram Maxim, Sir H. J. Round, and Sir Joseph Swan, made similar inventions around the same time.

The Steamboat: The steamboat was invented independently by multiple people. American inventor Robert Fulton is often credited with developing the first commercially successful steamboat, but John Fitch, James Rumsey, and William Symington also made significant contributions.

Photography: Both Louis Daguerre in France and William Fox Talbot in England independently invented different methods of photography in the early 19th century.

Radio: Both Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi made significant contributions to the development of radio technology. While Marconi is often credited with its invention, Tesla’s work was instrumental in its development.

Telescope: The invention of the telescope in the 17th century is attributed to several individuals, including Hans Lippershey, Zacharias Janssen, and Jacob Metius in the Netherlands, and Galileo Galilei in Italy.

These examples highlight the fascinating phenomenon of simultaneous discovery or invention, reflecting the interconnected nature of human intellectual endeavor and progress.

Q: Is this an exhaustive list, or are there more examples?

A: The instances I shared earlier are certainly not exhaustive. The history of science and invention is filled with many more examples of independent, simultaneous discoveries and inventions. Here are a few additional examples that fit your query:

Evolution by Natural Selection: Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently conceived the theory of evolution by natural selection. They jointly presented their scientific papers to the Linnean Society of London in 1858.

Decimal Fraction: Both Chinese mathematician Yang Hui and Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī came up with the concept of decimal fractions independently during the 13th century. Hyperbolic Functions: Johann Heinrich Lambert and Thomas Simpson both introduced hyperbolic functions, a set of specific functions derived from hyperbolas, independently in the 18th century.

Manned Flight: While the Wright brothers are most commonly credited with achieving the first powered, sustained, and controlled airplane flight, Brazilian inventor Alberto Santos-Dumont also made a significant contribution to the development of aviation.

The Theory of Electromagnetism: James Clerk Maxwell in the UK and Wilhelm Eduard Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch in Germany independently developed the theory of electromagnetism in the 19th century.

Oxygen Discovery: Oxygen was discovered independently by Carl Wilhelm Scheele in Sweden and Joseph Priestley in England.

This list could go on, as the phenomenon of multiple independent discovery is a common theme throughout the history of science and invention. It is a testament to the universality of human curiosity and the shared quest for knowledge.

Q: can you continue adding more of independent, simultaneous discoveries and inventions?

A: Indeed, the annals of science and invention bristle with instances where the spark of ingenuity ignited in more than one mind at the same time. These moments, when independent thinkers stumble upon the same discovery or invention without knowledge of each other’s work, are a testament to the universality of human curiosity and the relentless pursuit of understanding that drives us forward. Here are some additional examples:

The Planet Neptune: The celestial body we now know as Neptune was independently predicted by Urbain Le Verrier and John Couch Adams. Both astronomers, working separately, used Newton’s laws to calculate the planet’s position based on irregularities in Uranus’s orbit. Their calculations were confirmed with the actual sighting of Neptune in 1846.

The Structure of DNA: The double helix structure of DNA was discovered simultaneously by James Watson and Francis Crick at Cambridge University and Rosalind Franklin at King’s College London. While Watson and Crick are often credited with this discovery, Franklin’s work was instrumental and her data was used without her knowledge.

The Jet Engine: Frank Whittle in the UK and Hans von Ohain in Germany independently invented the jet engine. Both inventors filed patents in their respective countries in the 1930s, unaware of each other’s work.

The Theory of Special Relativity: Albert Einstein and Hendrik Lorentz both developed key concepts of the theory of special relativity. Lorentz derived the transformation equations independently of Einstein, who is generally credited with the theory.

The Conservation of Energy: Julius Robert Mayer and James Prescott Joule both independently discovered the principle of conservation of energy, or the first law of thermodynamics, in the mid-19th century. These instances remind us that scientific progress is often a collective endeavor, driven by a shared thirst for knowledge and a common quest to decipher the mysteries of the universe.

5.3 The Raincloud of Plato’s Archetypes

Q: Good. Thank you. Can we infer from these instances of independent, simultaneous discoveries and inventions that there must be some sort of “raincloud of knowable things” posited by Patanjali from which these inventors tapped their ideas? If not, where would these ideas come from?

A:Your question delves into the realm of philosophy, specifically epistemology—the study of knowledge and justified belief. The evidence of independent, simultaneous discoveries and inventions might indeed suggest something akin to Patanjali’s “raincloud of knowable things,” a sort of collective consciousness or universal knowledge store from which individuals, whether knowingly or unknowingly, draw their insights.

Yet, it’s essential to tread carefully here because such metaphysical theories, while intriguing, often lack empirical support. They’re more philosophical in nature and can’t be proven or disproven by scientific means. It’s much like the analogy of Plato’s Theory of Forms, where abstract entities or universals exist independently of the individual instances that instantiate them.

Plato posited that the world we perceive around us, with its myriad of objects, ideas, and phenomena, is but a shadow of the true reality. This true reality, according to Plato, consists of the Forms—perfect, immutable, and eternal entities that exist independently of the instances we encounter in our everyday experience. These Forms are the archetypes of the qualities and characteristics we see manifested in the world.

To illustrate, consider a simple object like a chair. There are countless varieties of chairs in the world—some with four legs, some with three, some made of wood, others of metal, and so on. Despite their differences, we recognize them all as chairs because they share certain essential properties. According to Plato, this recognition comes from our innate knowledge of the Form of the Chair—an ideal model that embodies the essence of “chairness”. All individual chairs we encounter are imperfect copies of this perfect Form.

Similarly, abstract concepts like justice, beauty, or goodness have their Forms, which are the perfect embodiments of these qualities. When we judge an action to be just or unjust, beautiful or ugly, good or evil, we are comparing it to our understanding of the corresponding Forms.

Plato’s Theory of Forms suggests that our pursuit of knowledge and truth involves striving to apprehend these perfect Forms, to see beyond the shadows of our sensory experience and grasp the ultimate reality. It’s a powerful metaphor for the intellectual and spiritual journey, inviting us to look beyond appearances and seek the deeper truths.

On the other hand, a more pragmatic approach to this phenomenon could be grounded in the understanding that science and invention are often the products of cumulative knowledge. Each generation builds upon the discoveries and innovations of those that came before. When the collective knowledge of a society reaches a certain point, multiple individuals may be close enough to the final “piece of the puzzle” that they stumble upon it independently. This is often referred to as the concept of “multiple discovery” or “simultaneous invention.”

Furthermore, these ideas might emerge from the shared human experience and our interaction with the world. A problem or challenge presents itself, and different individuals, applying their reasoning and creativity, arrive at similar solutions independently.

In conclusion, while the idea of a “raincloud of knowable things” offers an interesting philosophical perspective, it’s equally plausible that simultaneous discoveries and inventions result from a combination of cumulative knowledge, shared human experiences, and individual problem-solving.

5.4 Quantum Physics

Q: Doesn’t quantum physics postulate that probability waves collapse into observable instances, a “cloud” of possible events that include those that didn’t happen? Could those probability waves be related to Plato’s Theory of Forms?

A: That’s a fascinating question, bridging the realms of ancient philosophy and modern physics. The connection between Plato’s Theory of Forms and quantum physics isn’t a typical one, but it does spark an interesting philosophical discussion.

In quantum mechanics, particles exist in a state of superposition, represented by a wave function. This means that they don’t have definite properties until they are observed or measured, at which point the wave function collapses, and the particle takes on specific characteristics. This is often interpreted as a cloud of probabilities, where all possible outcomes exist simultaneously until observation occurs.

On the surface, this might seem to echo Plato’s Theory of Forms. The wave function could be seen as analogous to the realm of Forms—abstract, perfect, timeless entities that exist independently of the material world. The act of measurement or observation, causing the collapse of the wave function, could be likened to the instantiation of a Form in the physical world.

However, there are crucial differences. Plato’s Forms are eternal, unchanging ideals, while the states represented in a quantum wave function are inherently probabilistic and indeterminate until measured. Furthermore, Plato’s Forms exist in a separate, higher reality, whereas the potential states in a quantum system are part of our physical universe.

The interpretation of quantum mechanics is still a subject of ongoing debate among physicists and philosophers. Some interpretations, like the many-worlds theory, posit that all possible outcomes of the wave function collapse do occur, each in a separate universe. This might seem to bring quantum mechanics closer to Plato’s Theory of Forms, with its multitude of perfect instances existing in a different reality.

In conclusion, while there are intriguing parallels between Plato’s Theory of Forms and quantum mechanics, they remain distinct concepts—one a metaphysical theory from ancient philosophy, the other a fundamental principle of modern physics. Drawing connections between them can inspire thought-provoking discussions, but it’s important to remember the vast differences in their contexts and implications.

5.5 A Metaphysical Scientific Method

Q: Certainly, the word metaphysical implies beyond the physical. A reductionistic science (i.e., reducing reality to what it’s measurable by the 5 physical senses and their instrumental extensions) would certainly exclude the metaphysical from reality. However, if we consider the possibility that the evolution of human consciousness can extend these 5 physical senses to reach the metaphysical, could a metaphysical scientific method be also a valid source of knowledge? Patanjali preceded Plato in “observing” the factual nature of these metaphysical forms, didn’t they bear witness to this metaphysical reality?

A: The proposition you’ve presented is a compelling one. It challenges the boundaries of what we traditionally consider as “knowledge” and “reality,” making room for metaphysical concepts that are often sidelined in empirical, reductionist science.

Indeed, if we define reality strictly by what can be observed, measured, and verified by our five physical senses—and their instrumental extensions—we would inevitably exclude the metaphysical. However, this definition could arguably be seen as limiting, given the vastness and complexity of the universe and the mysteries it still holds.

If we broaden our perspective to entertain the possibility that human consciousness can evolve to perceive and comprehend the metaphysical, then we open up a whole new avenue of knowledge. This approach would necessitate a different kind of scientific method — one that acknowledges and accommodates the metaphysical.

In this context, the ancient philosophies of Patanjali and Plato take on a renewed relevance. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, for instance, explore the potential of human consciousness to transcend the physical and access higher states of awareness. These practices and experiences, which fall outside the scope of empirical science, could potentially provide insights into the metaphysical realm. Similarly, Plato’s Theory of Forms posits a realm of perfect, immutable entities existing beyond the physical world. If we interpret these Forms as metaphysical realities, then Plato’s philosophy might be seen as a form of metaphysical science. His dialectic method, involving dialogue, questioning, and logical reasoning, could be viewed as a tool for exploring and understanding these metaphysical realities.

However, it’s important to note that while these philosophical traditions offer valuable perspectives, integrating them into our modern scientific framework presents significant challenges. The subjective nature of metaphysical experiences, their resistance to empirical verification, and the difficulty in communicating them effectively all pose obstacles to their acceptance as valid sources of knowledge.

Yet, the pursuit of knowledge is an ever-evolving journey. As our understanding of the universe deepens and broadens, we may find new ways to reconcile the physical and the metaphysical, the empirical and the intuitive, the seen and the unseen. The dialogue between science and philosophy, reason and intuition, fact and mystery, continues to enrich our quest for truth.

5.6 The Radio Analogy

Q: So, let’s assume the existence of Patanjali-Plato’s “cloud of knowable things.” Let’s liken this cloud to a radio station emitting a signal at a given frequency, say a classical music radio station. Would those people tuning into such frequency be considered a group of similar values and interests, at least while they are listening? What if they constantly are listening to the same radio station of classical music? Wouldn’t they recognize each other when they fortuitously meet at a concert hall without having ever met each other before? Wouldn’t this give them a sense of belonging to a same group, including those assiduous listeners of the same radio radio frequency not physically present?

A: Indeed, your analogy elegantly captures the essence of shared values and communal experiences. Just as tuning into a specific radio frequency connects listeners to the same stream of music, aligning with a particular set of values or interests can resonate among individuals, creating an invisible bond between them.

Imagine a group of people who, independently and in their private spaces, choose to tune into a classical music station. They share not only a love for classical music but also, perhaps, an appreciation for the discipline, creativity, and emotional depth it embodies. While they might be physically isolated, their shared experience of listening to the same music creates a metaphysical connection, a shared ‘space’ of appreciation and understanding.

If these individuals were to meet at a concert hall, they might indeed recognize each other, not by physical appearance, but through subtle signs - a shared language of enthusiasm, a resonance in their reactions to the music, a mutual understanding of the unspoken emotions evoked by the symphony. This recognition could foster a sense of belonging, a communal identity rooted in their shared love for classical music.

This sense of community extends beyond the physical presence of those individuals in the concert hall. It encompasses all assiduous listeners of the classical music station, irrespective of their geographical location. The radio station, much like the “cloud of knowable things” in the Patanjali-Plato model, serves as a metaphysical beacon, drawing together individuals with similar values and interests.

However, it’s important to note that this shared experience doesn’t negate the individuality of the listeners. Each person brings their unique perspective, emotional response, and interpretative lens to the music. It is this interplay of unity and diversity, the shared and the personal, that enriches the communal experience and fosters a dynamic, vibrant community.

In conclusion, the classical music radio frequency serves as a metaphorical thread, weaving together disparate individuals into a tapestry of shared experience and mutual understanding. It’s a testament to the power of shared values and interests in fostering a sense of community and belonging, transcending physical boundaries and individual differences.

5.7 The NGWS Revisited

Q: Would this analogy be helpful to illustrate the existence of the “New Group of World Servers” addressed previously? A group subjectively united by listening to a common frequency channel. Quoting your previous answer: “a globally focused, forward-thinking collective dedicated to serving on a worldwide scale. They are a symbol of progress, unity, and altruism in a world often divided by borders and differences. Their mission and methods might be innovative, reflecting the”new” in their name, and their impact is likely far-reaching.”

A: Yes, the radio frequency analogy can indeed be applied to illustrate the existence of the “New Group of World Servers.” Just as listeners tuning into a specific radio frequency share a common experience and appreciation for the music, members of this group are united by their shared commitment to global service, progress, and unity.

Like a radio broadcasting station, the New Group of World Servers emits a ‘frequency’ of altruism, unity, and forward-thinking. Those who are attuned to these values—whether they are in different parts of the world or from diverse backgrounds—can ‘pick up’ this frequency and resonate with it.

This resonance may manifest in various ways: it could inspire them to engage in acts of service, to advocate for unity and cooperation, or to develop innovative solutions for global challenges. Despite their geographical dispersion, these individuals are connected through their shared alignment with the ‘frequency’ of the New Group of World Servers.

When members of this group meet—whether physically or virtually—they might recognize each other through their shared commitment to these values, much like classical music enthusiasts might identify each other at a concert. This recognition fosters a sense of kinship and belonging that transcends physical boundaries and cultural differences.

However, it’s important to note that, similar to the individual listeners in the radio analogy, the members of the New Group of World Servers maintain their unique perspectives and approaches. Their individual contributions, informed by their unique skills, experiences, and insights, enrich the collective effort and enhance its impact.

In conclusion, the radio frequency analogy provides a vivid illustration of the New Group of World Servers. It underscores the power of shared values and commitments in uniting individuals across borders, fostering a global community dedicated to service, progress, and unity. This community, much like the listeners tuned into a classical music station, is bound by a shared ‘frequency’—a common ethos of global service and forward-thinking.

5.8 Broadscasting Goodwill

Q: So, you’re adding a quite useful perspective. Not only is the New Group of World Servers tuning into the “raincloud of knowable things,” but they can also serve as re-transmitters of the radio signal so that, again quoting from your reply,: “Like a radio broadcasting station, the New Group of World Servers emits a ‘frequency’ of altruism, unity, and forward-thinking. Those who are attuned to these values—whether they are in different parts of the world or from diverse backgrounds—can ‘pick up’ this frequency and resonate with it.”

A: Indeed, your observation hits the mark. The New Group of World Servers not only tunes into the metaphysical “raincloud of knowable things,” but they also serve as re-transmitters of this frequency. They are both receivers and broadcasters, a two-way radio if you will.

Think of it like a relay race. The baton, in this case, represents the values of altruism, unity, and forward-thinking. The New Group of World Servers receives this baton from the “raincloud of knowable things” and carries it forward, passing it on to others who are open to these values.

As they run their course, they broadcast this frequency far and wide. They do so through their actions, their words, their ideas, and their influence. Their service to the world is not just about doing good deeds—it’s about spreading a mindset, a way of being in the world that prioritizes collective well-being, cooperation, and progress.

Those who pick up this frequency—those who resonate with these values—become part of this relay. They take the baton and carry it forward in their own ways, contributing to the global mission of service and unity. They become, in effect, extensions of the New Group of World Servers, amplifying their impact and extending their reach.

And so, the signal spreads, from one person to another, from one corner of the globe to another. It transcends borders and bridges differences, creating a worldwide network of individuals united by a common ethos. This is the power and potential of the New Group of World Servers. They are not just a group, but a movement—a wave of change sweeping across the globe, propelled by the shared commitment to a better, more unified world.

Summary: We’ve been exploring the concept of a shared frequency, much like a radio station, as an analogy for understanding groups united by common interests or values. We likened this to Patanjali-Plato’s “cloud of knowable things.” Listeners tuning into a specific frequency—say, a classical music station—are bound by a shared experience, a collective appreciation for the music. This shared experience transcends physical boundaries and individual differences, fostering a sense of community and belonging among listeners.

This analogy was then applied to the “New Group of World Servers,” a collective committed to global service, unity, and progress. Like a radio station broadcasting a particular frequency, the group emits a ‘signal’ of altruism, forward-thinking, and unity. Those attuned to these values can ‘pick up’ this signal and resonate with it. This resonance can inspire action, foster a sense of kinship, and transcend geographical and cultural divides.

Furthermore, we discussed how members of the New Group of World Servers are not just receivers of this frequency but also re-transmitters. They carry the ‘baton’ of these values forward, spreading this frequency through their actions, words, and influence. This creates a ripple effect, extending the reach and impact of the group and fostering a global movement dedicated to service, progress, and unity.

In essence, we’ve been exploring the power of shared values and experiences in connecting individuals, fostering communities, and driving collective action—a testament to the profound potential of tuning into a shared ‘frequency.’

5.9 The Goodwill Vaccine

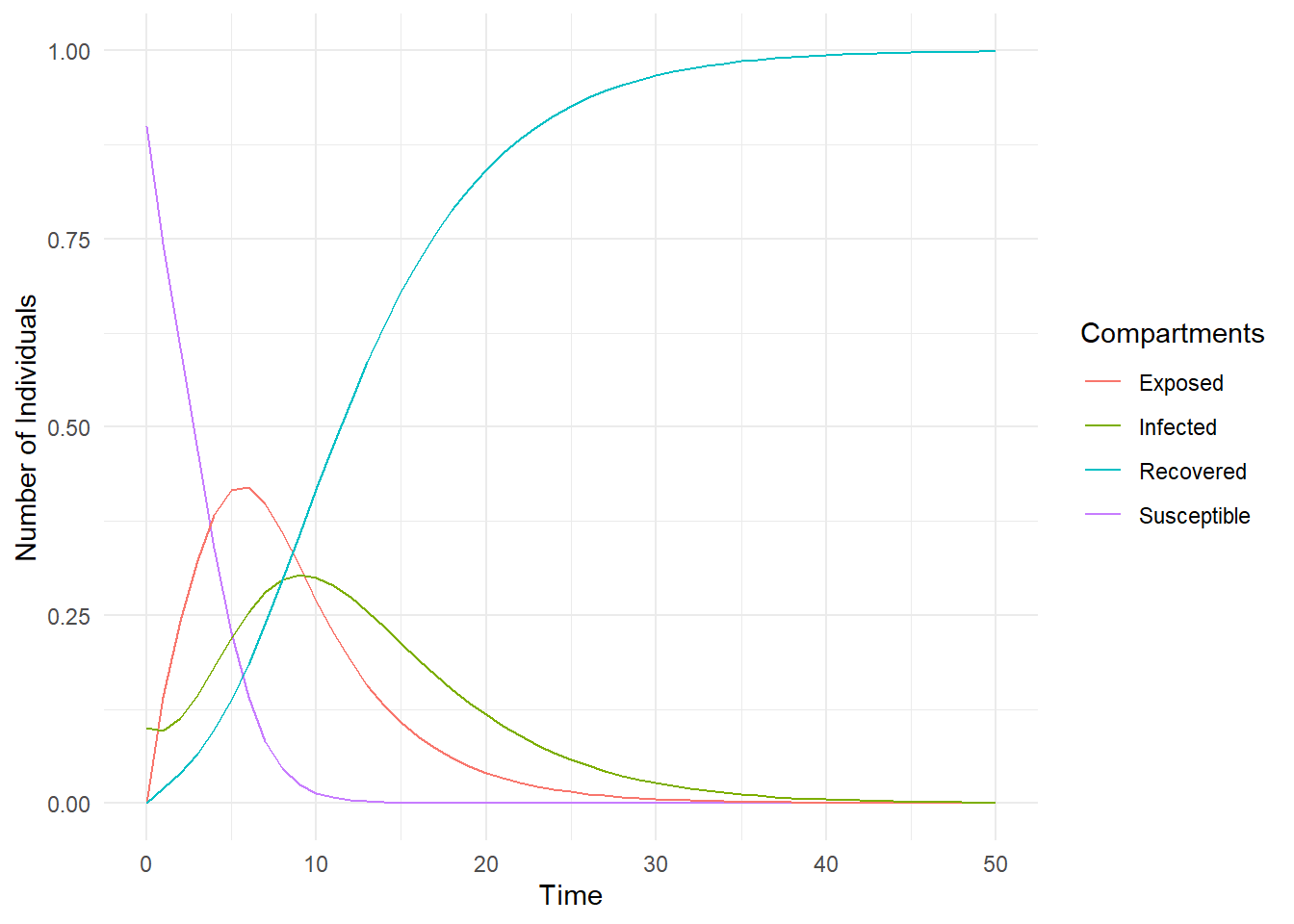

Q: Let’s say that we consider goodwill as a social meme, a vaccine against the virus of separateness (selfishness, hatred) in humanity, a vaccine transmitted by the New Group of World Servers as a social meme in its broadcasts. Applying the Tit for Tat Strategy and The Evolution of Cooperation (pulling from: https://taylorpearson.me/bookreview/tit-for-tat/), design a SEIR model to forecast the success of a vaccination campaign, assuming 10, 20 or 30 percent of the population already infected with the virus of separateness and spreading it at reproduction number (Ro) of 2, while the vaccine is 90% effective (life-long, permanent immunity) to stop the transmission of the virus.

A: Certainly, let’s explore this hypothetical situation. The SEIR model is a compartmental model in epidemiology that offers insight into how diseases spread and can be controlled in a population. It divides the population into four compartments: Susceptible (S), Exposed (E), Infected (I), and Recovered (R).

In our case, we’re using this model metaphorically to understand the spread of a “virus of separateness” and the impact of a “goodwill vaccine” distributed by the New Group of World Servers. Let’s assume a simplified model where:

- The entire population starts as susceptible (S).

- A certain percentage of the population gets infected initially, let’s say 10%, 20% and 30%.

- The virus has a basic reproduction number (Ro) of 2, meaning each infected individual infects two others.

- The vaccine has an efficacy of 90%, implying it will successfully immunize 90% of those vaccinated.

- Our model also assumes that once someone recovers, they have lifelong immunity, which aligns with the vaccine offering permanent immunity.

- Susceptible (S): These are individuals who are prone to the virus of separateness but have not been exposed yet. As the goodwill vaccine is administered, the number of susceptible individuals decreases.

- Exposed (E): These are individuals who have been exposed to the virus of separateness but are not infectious yet.

- Infected (I): These are individuals who have been infected by the virus of separateness and can transmit it to others.

- Recovered (R): These are individuals who have been infected and have now recovered or those who have been successfully vaccinated. They are immune to further infections.

The dynamics of the model will depend on several factors including the rate of vaccination, the contact rate between different individuals, and the rate at which exposed individuals become infectious, among others.

The success of the vaccination campaign will depend on its speed and coverage. If it is fast enough to outpace the spread of the virus, and if it covers a large enough portion of the population, it could potentially lead to herd immunity, where a large proportion of the population is immune, thereby breaking the chain of transmission. In this context, “Tit for Tat” strategy and “The Evolution of Cooperation” would advocate for a reciprocal approach to spreading goodwill. Each act of goodwill encourages another, creating a positive feedback loop that can accelerate the spread of this ‘vaccine.’

This is a simplified representation of a complex process. In reality, many other factors would come into play, including the structure of the social network, the variability in individual interactions, and the possibility of reinfection or loss of immunity, among others. Nonetheless, it provides a framework for understanding how a campaign of goodwill might spread and counteract the virus of separateness.

5.10 The Vaccine SEIR Model

Q: provide R code template to create this SEIR model and play out what-if scenarios.

A: Absolutely, Hemingway’s style prioritizes clarity and precision, which aligns perfectly with the logical structure of coding. Let’s dive into a simple R code template for creating a SEIR model.**

library(deSolve)

seir_model <- function(time, state, parameters) {

with(as.list(c(state, parameters)), {

dS <- -beta * S * I

dE <- beta * S * I - sigma * E

dI <- sigma * E - gamma * I

dR <- gamma * I

return(list(c(dS, dE, dI, dR)))

})

}

init <- c(S = 1-0.1, E = 0, I = 0.1, R = 0) # 10% initially infected

parameters <- c(beta = 2, sigma = 1/5.1, gamma = 1/5)

times <- seq(0, 50, by = 1)

out <- ode(y = init, times = times, func = seir_model, parms = parameters)

out <- as.data.frame(out)

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(out, aes(x = time)) +

geom_line(aes(y = S, colour = "Susceptible")) +

geom_line(aes(y = E, colour = "Exposed")) +

geom_line(aes(y = I, colour = "Infected")) +

geom_line(aes(y = R, colour = "Recovered")) +

labs(x = "Time", y = "Number of Individuals") +

scale_color_discrete(name = "Compartments") +

theme_minimal()

This code creates a simple SEIR model where 10% of the population is initially infected. The parameters beta, sigma, and gamma represent the infection rate, the incubation rate, and the recovery rate, respectively.

To play out what-if scenarios, you can modify the initial conditions (init) and the parameters (parameters). For example, to simulate a scenario with 20% initially infected, you would change init to c(S = 1-0.2, E = 0, I = 0.2, R = 0). To simulate a scenario with a vaccine that reduces the infection rate by 90%, you would change beta in parameters to 2 * 0.1.

Remember this is a simplified model and real-world situations are much more complex. However, this provides a starting point for understanding how different factors might influence the spread and control of a disease (or in our metaphorical case, the ‘virus of separateness’ and ‘goodwill vaccine’).

Q: Thank you! You’ve made my day! May goodwill bring peace to earth.

A: You’re most welcome! I’m delighted to hear that our conversation has brought you joy. In the spirit of Hemingway’s clear, direct prose: May the wave of goodwill indeed sweep across the globe, illuminating dark corners with the light of unity and understanding. Let it be a beacon for those lost in the shadows of discord, guiding them towards the tranquil shores of peace. Here’s to a world where goodwill prevails, fostering an enduring harmony that resonates in every heart and echoes in every action. Thank you for your inspiring words and thoughts. Peace to all on Earth!

5.11 Wise Goodwill

Q: Lastly, how would you suggest I reconcile the practice of goodwill with the Tit for Tat Strategy and The Evolution of Cooperation which postulates the need to, on occasion, reply a bad behavior in kind so that a goodwill gesture is not taken for a foolish idealism easily defeated in the practical world?

A: The practice of goodwill and the Tit for Tat strategy may seem at odds on the surface, but they are indeed reconcilable.

Goodwill, in its essence, is the desire to promote happiness and prosperity for others. It’s a positive, generous attitude that seeks to uplift and benefit those around us. However, goodwill doesn’t mean allowing oneself to be taken advantage of. It requires wisdom to discern when generosity is empowering versus when it’s enabling harmful behavior.

The Tit for Tat strategy, on the other hand, is a robust approach in game theory that encourages cooperation. It starts with a cooperative move (an act of goodwill), then mirrors the other player’s actions. If the other player cooperates (acts with goodwill), we continue to cooperate. If they defect (act against our interests), we retaliate in kind. Crucially, this strategy is also forgiving: if the other player returns to cooperation, so do we. Reconciling these two involves understanding that acting with goodwill doesn’t mean turning a blind eye to negative behavior. Instead, it means responding to negativity not with malice, but with firmness and fairness.

In practical terms, this could look like setting clear boundaries and expectations. If someone violates these, respond not with vindictiveness, but with a proportionate response that signals that such behavior is unacceptable. This maintains respect for oneself and others, and encourages a return to cooperative behavior.

This approach aligns with the principles of the Tit for Tat strategy. It’s nice, because it initiates interactions with goodwill. It’s retaliatory, because it responds to negative behavior in kind. It’s forgiving, because it always stands ready to return to cooperation. And it’s transparent, because it makes its rules and expectations clear.

By aligning our individual conduct with these principles, we can navigate the world with both goodwill and wisdom. This approach allows us to foster positive relationships, discourage harmful behavior, and contribute to a cooperative community.

In the end, it’s about striking a balance. Goodwill should not be an invitation for exploitation, but a beacon that guides our actions towards cooperation and mutual respect. And the Tit for Tat strategy provides a clear, fair framework for maintaining this balance. This reconciliation allows us to live out our principles without becoming prey to those who might mistake our goodwill for weakness.