6 Module 2: The Context

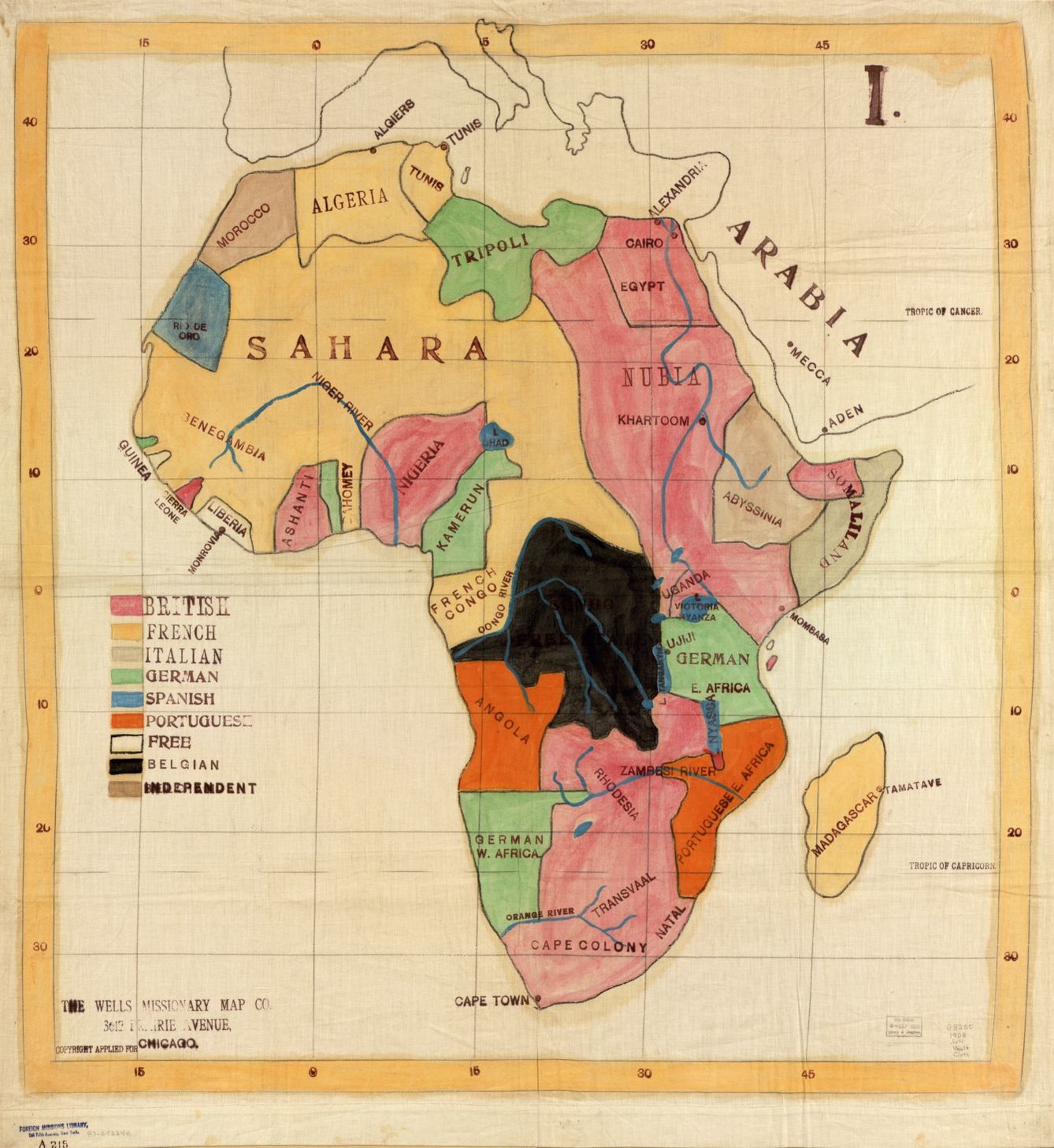

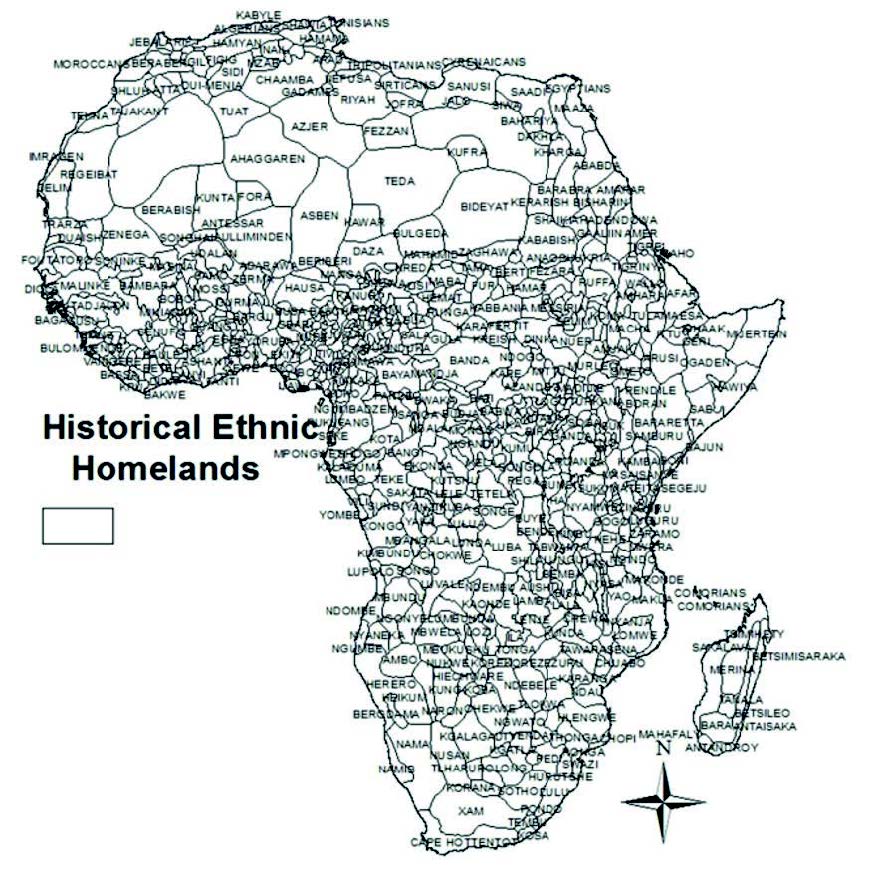

Figure 6.1: Source: Library of Congress, (1908)

In this section of the course, we will focus our attention on different aspects that will help us understand the context of the countries and societies we study. We will explore different theories and approaches that are many times contradictory and assess them based on evidence.

Topics Covered:

- History and development: Pre-colonial period and trade of enslaved persons; colonial period; after independence

- Conflict and development

- Politics and development

- The role of institutions

6.1 History and development

6.1.1 Pre-colonial Africa and Trade of Enslaved Persons

The first topic that we will analyze in this section is the role of history for development. Up to what extent does history influence the development path of a society? This interdisciplinary analysis field is quite recent, but it has been prolific, so we will explore how different historical events have affected development in Africa and beyond.

Before colonization, Africa had a very different configuration than the one we see today. A large share of the continent was unoccupied, and the population was widespread. Contrary to what we see in western societies, African groups were hardly centralized and did not have strict hierarchies. People tended to live in smaller groups and did not recognize a robust central authority (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2020). Just a few groups, such as the Kingdom of Ashanti, in what is now Ghana, the Lozi Kingdom in what is nowadays Zambia and the Zulu Kingdom in Southern Africa, had a more complex and centralized political system.

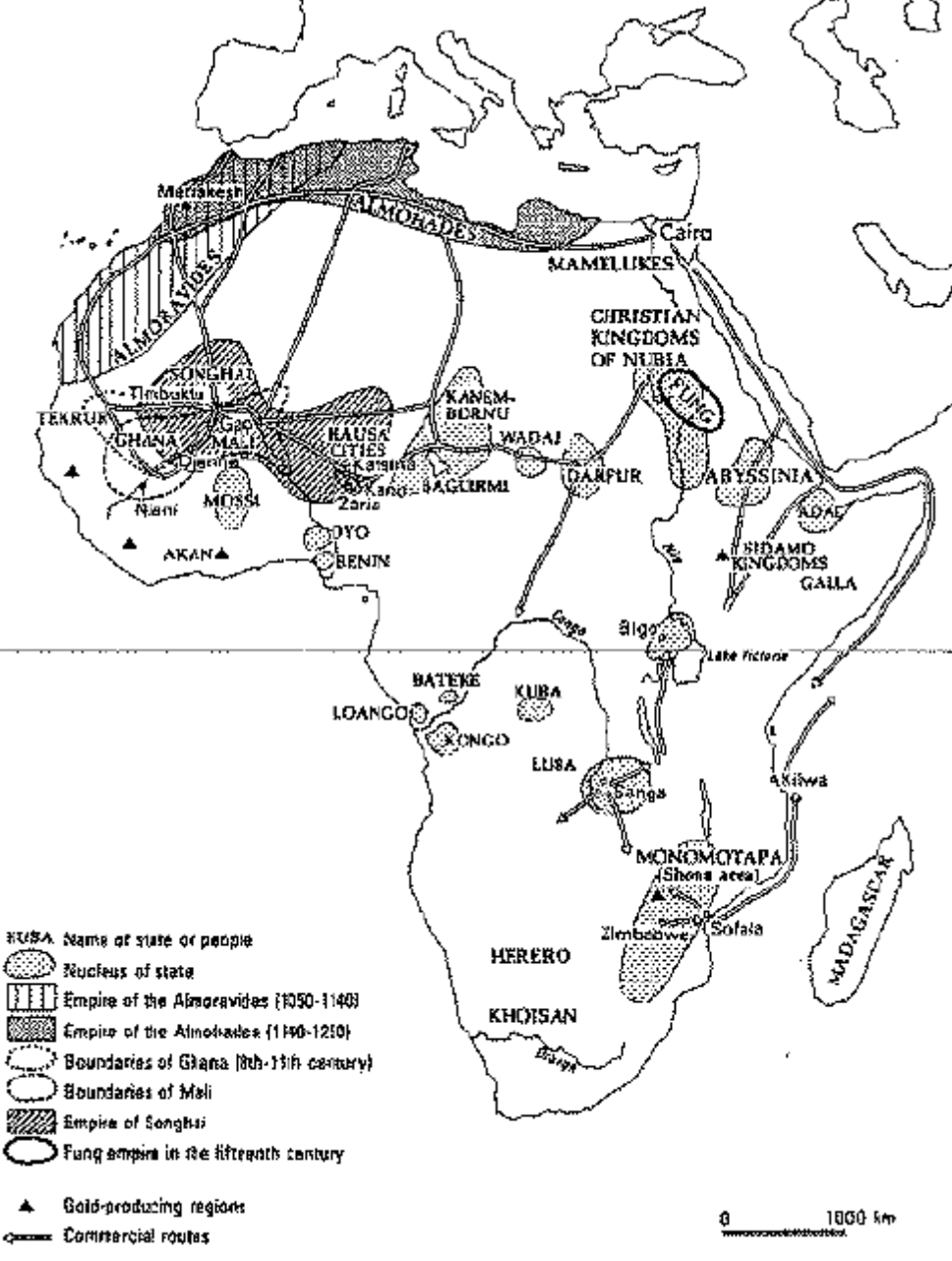

Figure 6.2: Pre-Colonial States in Africa. Ayittey, (2006)

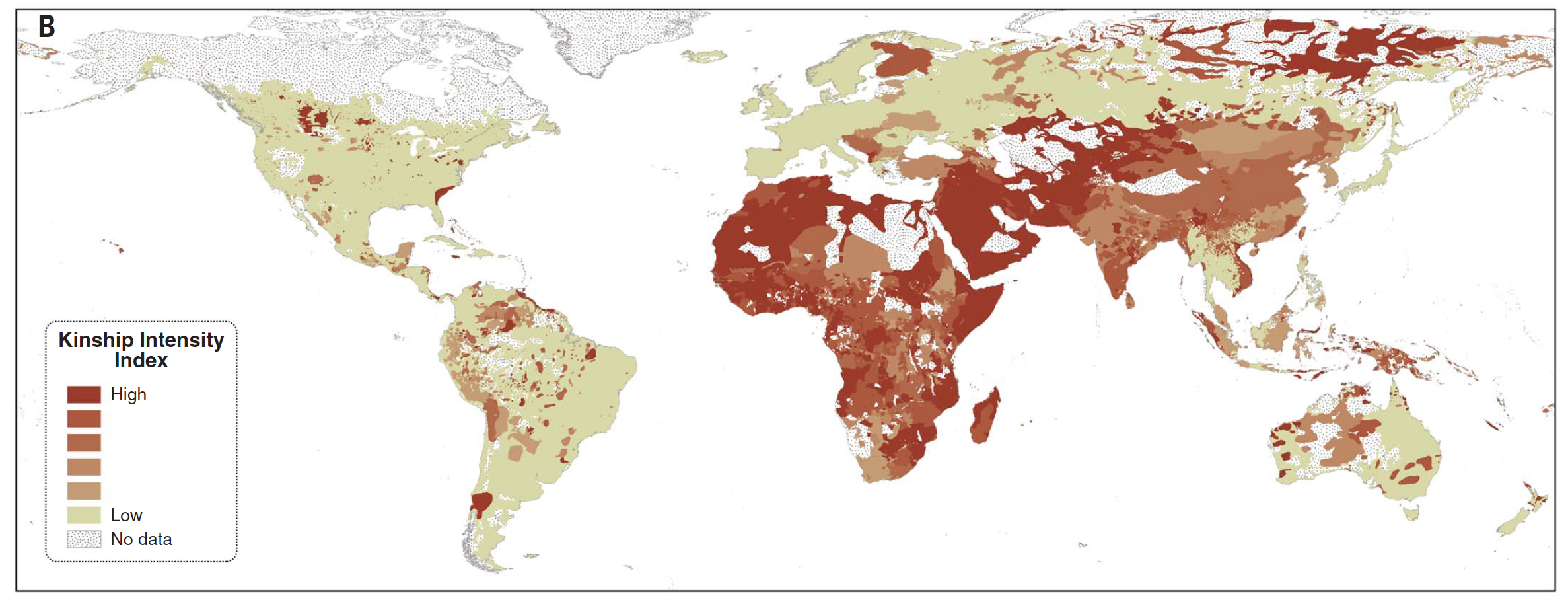

Still, even if many of these groups were not strictly hierarchical, African peoples were characterized by intensive kinship norms 7. According to Shulz et al. (2019) this element has affected the relationship with the family unit and may affect more extensive cooperation.

Herbst (2000) argues that although the territorial boundaries in pre-colonial Africa were not set in the same way as European boundaries, it does not mean that the state did not exist. However, since mapping was not available, it was hard for states to control large areas of land, so the state’s reach was more limited. In the same sense, warfare did not lead to the control of more land, as it happened in Europe, but rather translated to the control of other humans, which were then traded. Within this context, states were dynamic and fluid, with outlying territories separating from the center.

Figure 6.3: Kinship intensity index. Schulz et al., (2019)

Since the 15th Century, different kingdoms, including the Ashanti, had contact with European traders, with whom they traded gold, ivory, and enslaved persons. This argument goes against the traditional argument on the Triangular slave trade that argues that. In contrast, Europe provided manufactured goods (such as guns), Africa ‘just’ provided enslaved people transported to the Americas for the production of commodities that were then transported to Europe. Africa was also the source of other goods valued by the Europeans.

Nevertheless, the slave trade did have detrimental effects on Africa’s economic, social, and political development. One of the first and significant studies in this regard is Nunn (2008), who shows that countries that were the source of most of the enslaved persons between 1400 and 1900 are the poorest in Africa nowadays. This finding is quite robust to different specifications, and Nunn shows that, in fact, at the point at which this practice took place, the source of these persons were wealthier than other areas. This indicates that it is not the fact that these areas never developed, but that the slave trade had a detrimental effect on these peoples. These findings are relevant, as Nunn explains that 72% of the income gap that currently exists between Africa and the rest of the world would not exist, had the Atlantic slave trade never happened.

Other authors, such as Green (2013), Whatley and Gillezeau (2011), and Whatley (2014), show that the slave trade caused ethnic fractionalization, and lower institutional quality in locations closer to the ports of shipment. Zhang and Kibriya (2016) show the higher prevalence of conflict in areas with a more significant slave trade intensity. These outcomes may explain some of the mechanisms behind the poor economic, political, and social conditions in many African regions.

An additional effect of the slave trade was the arousal of polygyny, and this may also seem to have contemporary effects for the livelihoods of African peoples. This is because in polygynous relationships, women are more likely to have sexual partners than their husbands, which has led to an increase in HIV rates in these areas, as Bertocchi and Dimico (2015) show.

However, what caused the trade of enslaved persons? Although many structural factors have not been examined yet, some research has shown that abnormally cold years led to an increase in the trade of enslaved persons (Fenske and Kala, 2015) and that uneven terrain could escape the slave trade (Nunn and Puga, 2015). Besides, Fenske and Kala (2016) show that the abolition of the slave trade by the English in 1807. However, it indeed reduced the trade of enslaved persons; it also increased violence and coercion within the region. This indicates that the way the trade of enslaved persons happened led to a reconfiguration of the region that had lasting effects and that abolishing this practice also generated detrimental effects.

6.1.2 Colonization and Development

As we see in the case of the trade of enslaved persons, African peoples fought against colonization, just as it happened in Latin America. The relationship was more complicated than what Western history textbooks acknowledge.

Between the mid-1800s and 1900, the ‘Scramble for Africa’ took place, with European powers signing treaties and deliberately dividing the African continent, without further knowledge of the terrain or the peoples that occupied that land. This had effects on the further development of the continent. As argued by Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2016), the division of the continent led to the fragmentation of ethnic groups. This, in turn, led to ethnic discrimination, inequality, and conflict.

Figure 6.4: Ethnic Groups in Africa. Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2016)

In addition to this, the partition of Africa led to the creation of multiple landlocked countries. In the continent, out of the 49 countries, 16 are landlocked. Why is this an issue? Well, landlocked countries face higher transportation costs than countries that are next to the coast. Besides, these countries largely depend on the conditions of their neighbors to trade. For instance, if a neighboring country faces political upheavals or civil war, international trade can be even more challenging, if not impossible.

During colonization, European settlers were based in areas closer to the coast or in clearly delimited areas with a more favorable climate. From here, roads and railways were built towards areas where the natural resources were located. These cities played an essential role as the entry point of European settlers and the place where exports and imports took place. This is why most of the capitals of African countries are located on the coast (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

However, the fact that Europeans were established in particular areas meant that they only invested in infrastructure development in these areas. To control the rest of the territory, they relied on traditional leaders that were co-opted and forced to keep control of these areas, further increasing the inequality among different tribes and setting the ground for future conflict, for the emergence of ‘Big-men’ after independence, and neo-patrimonialism.

Even with the assistance of traditional chiefs, the Scramble of Africa created huge countries, with territories that were vast and hard to penetrate. This limited the reach of the state and prevented it to ‘monopolize violence.’ This, in turn, has prevented the emergence of state capacity and limited the development of multiple regions.

Although there is a wide range of variation among the colonizers, all the systems were characterized by the brutality of the methods used to keep the population under control. In some cases where cash crops were produced (notably in British colonies), Africans were able to use these as a way to compete against the Europeans and promote their development (Austin, 2014)

A seminal paper, Acemoglu, Robinson and Johnson (2001) shows that colonization impacted every region involved. For the colonizers, it led to the development of some European countries, while it reduced growth in others. However, the main impact happened in the colonized regions. In this case, the effects depended on the initial conditions of the countries.

The authors’ central argument (which has been controversial, to say the least) is that the disease environment faced by the Europeans mattered a lot to the type of institutions set in the colonies. In areas where Europeans had a lower chance of surviving, they would create extractive institutions, that could allow the colonizers to extract resources at a higher pace. In cases with lower risks for the settlers, the type of institutions would lead to a more comprehensive state. These institutions have had persistent effects and could explain variations in development across colonized regions (more on that later in this section).

6.1.2.1 Is There a Case for Colonialism?

Short answer: NO.

Although there have been some academic attempts to make a case for colonialism, using outlier cases such as Singapore, or bringing forward arguments on how colonizers brought education and other institutions to the countries colonized.

However, what these arguments miss is the terrible damage colonization brought to the peoples colonized and how enduring these effects have been. Colonial practices were brutal, and colonizers had many times little regard for human rights and sovereignty. “Modernization” practices had elements of separation of groups that were more similar to the Western phenotype and promoted segregation, conflict, and forced assimilation.

Exploring missionary activity may provide some guidance to examine the effects that ‘development’ programs conducted during the colonial period had. For the most part, this is because the provision of public goods was outsourced to missionaries, with colonial institutions focused on the investments on public goods that could allow them to access and extract the local resources (minerals or agricultural products).

Cagé and Rueda (2016) examine this issue and argue that missionary activity was heterogeneous across the African continent, and therefore, its effect is hard to calculate. Still, there are two areas where the effects are more clear. The first one is the introduction of the printing press, as it was used to print the Bible in the local languages to facilitate the introduction of Christianity, but it remained in certain regions for other uses. According to the authors, the presence of a printing press is correlated to higher media consumption and social capital. According to the authors, the mechanism behind this may be literacy and not necessarily the adoption of specific values.

The second area is health. Missionaries were the first ones to invest in ‘modern’ medicine in Africa, with 150 missionary doctors and more than 235 nurses working across the continent. This provision of health remained after independence. However, the introduction to Christianism also affected the local values and the sexual behavior adopted. The authors find that areas that are closer to areas closer to a historical mission settlement have a higher prevalence of HIV today. This may be related to the attitudes adopted towards the use of contraceptives, especially condoms.

6.1.3 After Independence

In many ways, the patterns of colonialism set the ground for the development of African politics after independence. During the colonial period, certain groups were supported over others, leading to the emergence of “Big Men”, leaders that became powerful as colonial governments gave them the task of controlling the population, in areas where the colonial settlers did not penetrate (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019). As Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson (2014) put it, “[these] chiefs were accountable to their occupiers, but the system did not require them to be accountable to their people.”

At the time of independence, these new leaders were in front of the opportunity to control vast territories. However, they were threatened by other Big Men that also wanted to gain control in a context with ethnic communities that did not believe themselves as being part of the same nation.

In response, these Big Men introduced a series of neo-patrimonial policies. Leaders used their power to break the rules, using their ethnic identity to distribute gifts (from jobs to assets) to maintain power. This led to a system in which coercion and co-optation worked in unison to maintain power, and fragile authoritarianism emerged (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

In addition to this dimension, after independence, African countries faced another conundrum: how to promote economic growth? With deficient levels of literacy and poor infrastructure, governments had to create different ways to promote development. At the same time, they had to generate a sentiment of unity among the population in these artificial states.

Different patterns took place. In certain countries, such as South Africa, the government passed into the hands of European settler communities, and racial segregation was pursued. There was a shift towards pre-colonial traditions in other regions, such as ujamaa in Tanzania (extended family in Swahili). This involved the push for unifying policies, such as creating one-party states, with the idea that these would push people to the ‘same side’ while allowing competition at the local level and other types of -partial- competition in specific contexts. In certain countries, such as the DRC, competition was banned at any level, with the national leader, Mobutu Sese Seko, recentralizing power. But this was also the opportunity for governments to distance their countries from the colonial influence, leading to the creation of Pan-Africanism.

However, bear in mind that the independence process took place at the same time than the Cold War was developing, and African states participated as proxy areas for conflict, with both the East and the West wanting to gain influence in these areas. This had important consequences for the region’s political and economic configuration, as leaders were supported by the international community (East and West) irrespective of their domestic policies, as long as they joined one faction.

At the end of the Cold War, these leaders lost the unconditional support they had. As Fukuyama (1992) argued, ‘The End of History’ had arrived with the dominance of Western democracy8. This has not been the outcome, even if there has been a shift towards governance and institutions as tools for development in low- and middle-income countries. Still, as we will see later in this section, African countries have followed different political paths.

6.2 Conflict and development

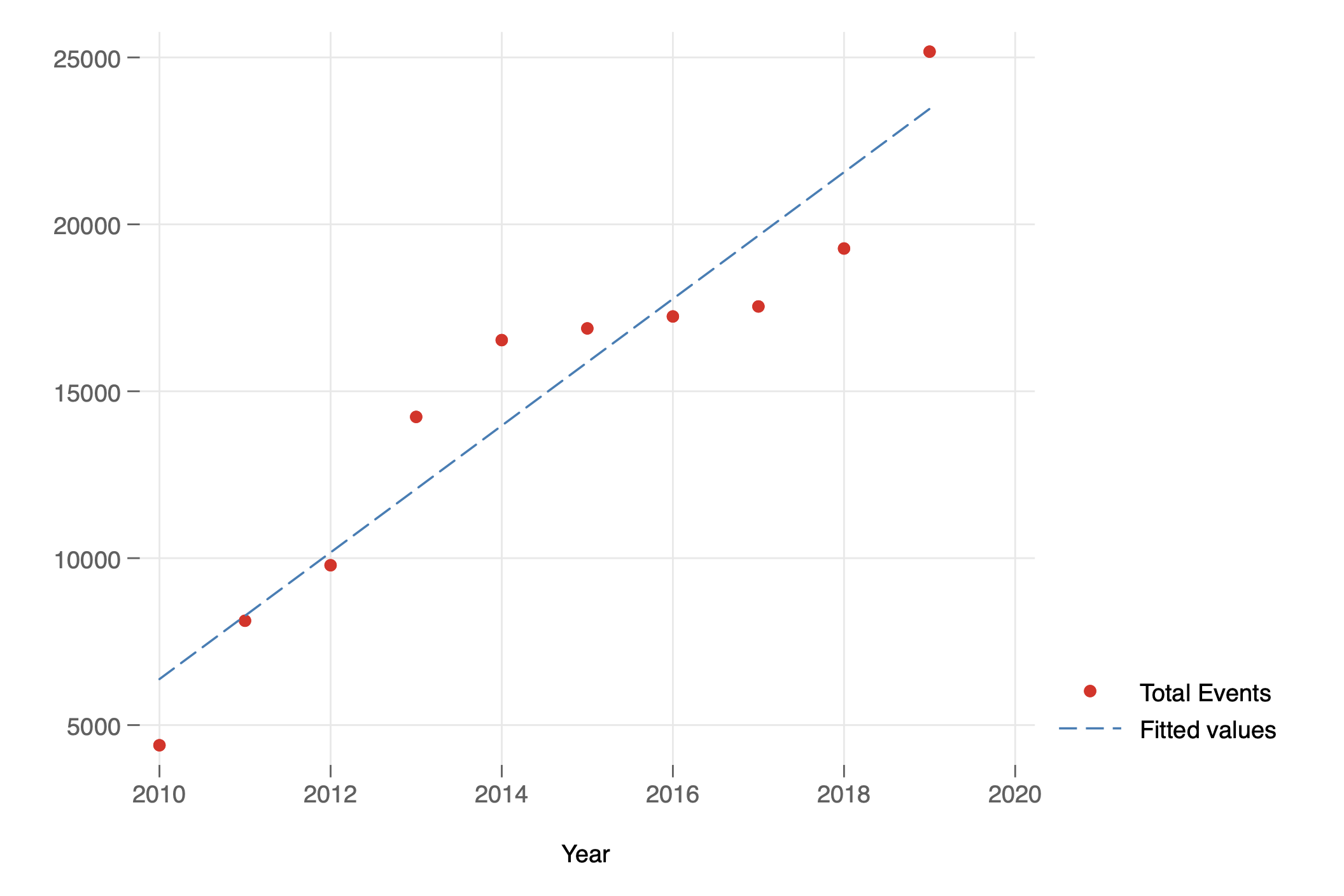

After the Cold War, there was a shift in the type of conflicts across the globe. In Sub-Saharan Africa, there has been an abundance of civil conflict. The following chart shows the evolution of conflict across time, and the predicted pattern of conflict, with a positive trend indicating the increase of conflict events.

Figure 6.5: Conflict Trend 2010-2019. ACLED (2020)

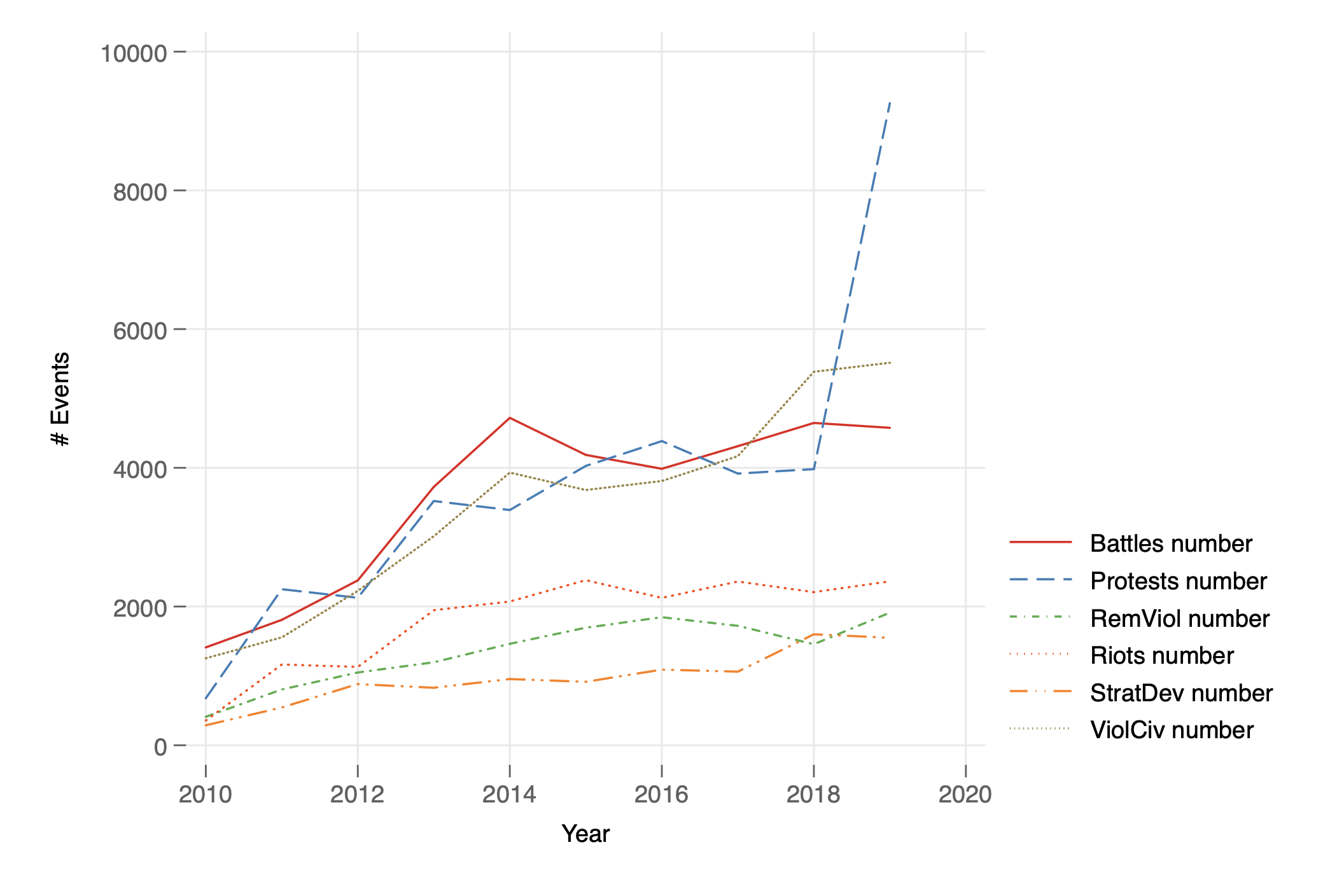

However, the configuration of conflict has changed, with protests becoming mainly the primary source of conflict in the region. Still, battles (civil conflict) remains high.

Figure 6.6: Conflict Trend 2010-2019. ACLED (2020)

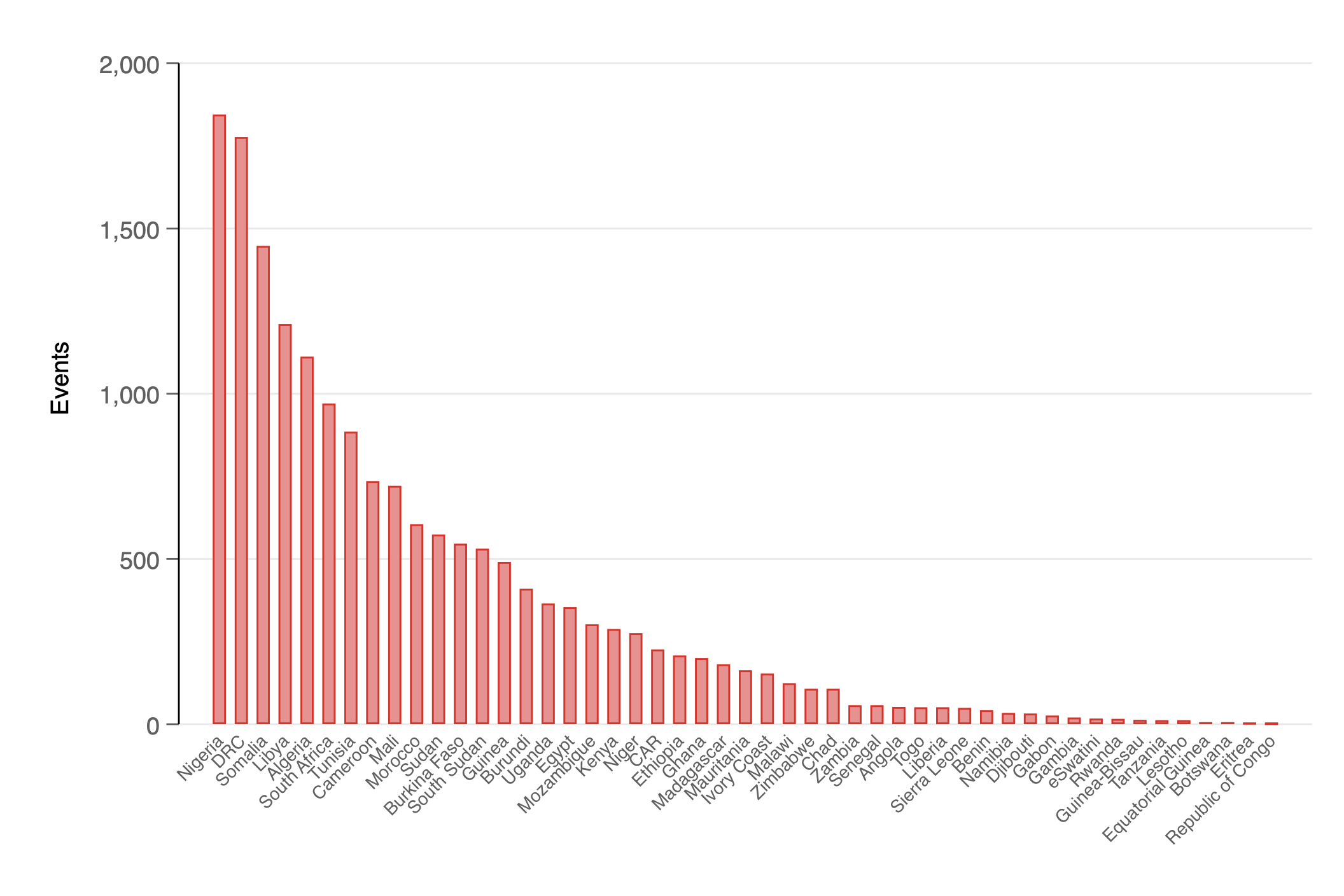

Conflict is not equally persistent across the continent, with most of the violence concentrated in some states. The following graph shows the distribution of conflict events between January and July 2020 across African countries. In the seven months, two countries had more than 1,5000 conflict event9.

Figure 6.7: Conflict Trend 2010-2019. ACLED (2020)

What causes this substantial persistence of conflict? How is this related to development? There are different theories on this subject.

It has been argued that civil war is related, at least in part, to the presence of natural resources. In Africa, Angola, DRC, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Sudan are the primary examples. However, finding a pattern of causality is hard. For instance, as Ross (2004) argues, there might be other elements that are related to conflict that may lead to a country to highly depend on its natural resources, leading to a spurious relationship. Still, he does a literature review and finds that oil exports are related to civil war, whereas resources that can be looted are correlated with the duration of conflict. Why would that be? One answer might be because controlling resources give access to economic gain. Different groups assess their probability to control these resources and the potential costs. These costs depend on different factors, such as the characteristics of the terrain, the reach of the state, among others (See, for instance, Fearon and Laitin (2003)). Sanchez de la Sierra (2020) argues that, for the DRC’s case, minerals that cannot be concealed lead to the establishment of warlords (‘stationary bandits’) that tax and protect the mines. Contrary to this, the presence of minerals easy to conceal leads to stationary bandits in the villages, leading to the establishment of sophisticated fiscal and legal administrations to extract revenue. Although accessing minerals as a source of wealth is the goal of these warlords, they provide some of the functions that the state does not provide in these areas.

Also, ethnic diversity may provide a ‘motivation’ for conflict, as it may work as a source of grievance, although the evidence is mixed. For instance, Esteban, Mayoral, and Ray (2012) empirically test if polarization, fractionalization, and ethnic differences influence conflict in 138 countries throughout 1960–2008. They find that countries in the top 20% of ethnic polarization in the sample have a probability of conflict of 29%. In contrast, countries in the bottom 20% show a 13% of conflict, after taking into account (controlling for) other factors that are also important to explain conflict. These findings are supported by those of Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2005).

Chabal and Daloz (1999) expand the argument of violence in Africa to include it as a political tool used by the elites to control the population. The authors normalize violence and state that it is used by the elites to control the system. Although the book was criticized by missing empirical understanding, it did provide a good notion of how everything that happens inside the system may be calculated and used as a political tool to link the formal and informal economy and politics worlds. This includes civil war, which, although not seen as desirable, may be understood, according to the authors, as unavoidable to bring necessary change.

How could civil war and violence affect development? Although this question may require a full session, we can certainly touch on different elements, and we will further discuss them in class. Of course, the main effects are related to the devastation and the loss of lives and infrastructure, that translate in low economic growth and poor development among the population. Nevertheless, the effects go much beyond that. Conflict leads to a lack of trust, leading to a sense of continuous tension. It also makes state-building harder, from the material perspective, but also because state weakness was at the source of conflict. However, there are cases in which the reconstruction process has worked. The most evident case possibly is Rwanda after the 1994 genocide. However, South Africa could also be included, among others10.

Nevertheless, conflict does not only affect countries that struggle with it. As shown by Adhvaryu et al. (2018), countries that have resource-rich neighbors tend to have lower economic outcomes, as the neighbors have a higher probability of being involved in a conflict.

Still, Aili Mari Tripp (2015) indicates that post-conflict states in Africa have also been able to move forward. She specifically argues that women have played a crucial role in the reconstruction of African countries at the outset of conflict and that a by-product of war in countries around the continent has been a higher political leadership rate for women.

6.2.1 Corruption

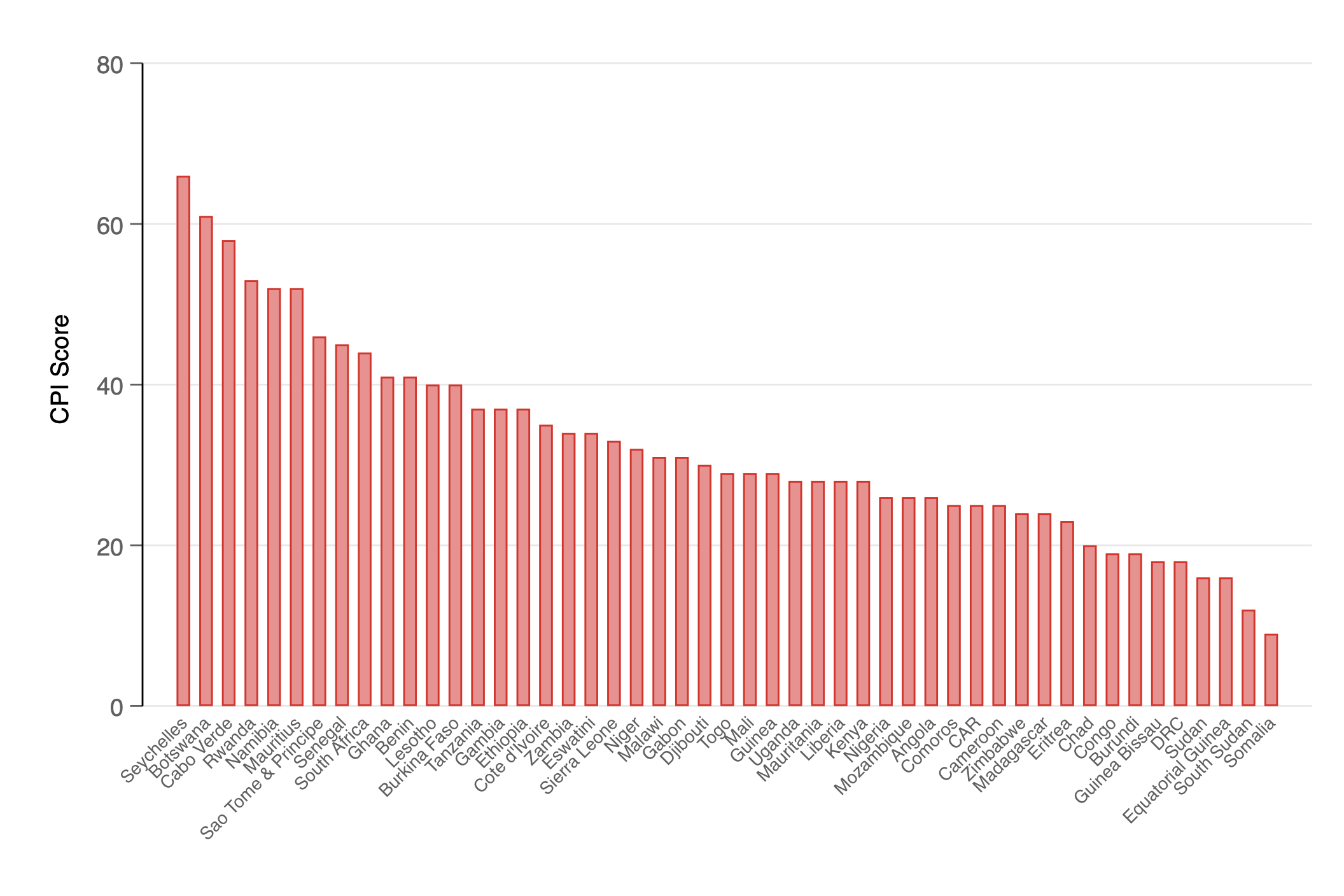

Even though we have focused mostly on civil war in this section, we have also talked about the role of the elites in sustaining violence. Part of this works because of the system’s configuration that allows for the presence of corruption as part of the informal system. The graph below shows the Corruption Perception Index of 2019 for African countries. The index gives a score between 0 to 100 to countries, with 100 being the least corrupt country.

Figure 6.8: Corruption Perception Index. Transparency International (2020)

Although the average score of the region is 32/100, there is some variation among the results, with eight countries having a score below 20 and 6 countries scoring higher than 50 in the index. But this index may not say much without some evidence on how it takes place.

Titeca and Thamani (2018) provide this evidence for the DRC case, a country that has persistently shown a low index. The authors show how corrupt cabinet ministers channeled resources to president Joseph Kabila to keep their positions and avoid being prosecuted for receiving payments from business people and other politicians at lower levels. This expands the concept of neo-patrimonialism to show that it travels in both directions: from top to bottom, but also from the bottom to the highest levels.

Corruption also occurs in the form of rent capture and the spread of political elites’ presence into the economic sector. Evidence on how this works exists across the region, with government members showing vested interests in enterprises.

However, international actors have also been essential players in this corruption network. A large number of corruption scandals have involved multinational companies that pay bribes, international banks, and even international governments (tax havens that keep high levels of secrecy). Corruption in the aid sector is also prevalent, and this may put many developmental and humanitarian programs at risk.

At the local level, the population participates, voluntarily or not, in the process of bribery and corruption. In this case, although women participate to a lower degree in these practices (Transparency International 2019), they are also more vulnerable to cases of sextortion for the provision of basic services (Transparency International, 2019).

6.3 Politics and development

Democracy is a term difficult to define. In political science, there have been candid discussions to agree on what democracy is. It is clear that democracy \(\neq\) elections, even if the term “electoral democracy” has been coined to classify countries that hold elections. Since the 1990s, most African countries hold elections, even if they are not entirely regular and if the results are many times dubious. Nevertheless, most African leaders have found on elections a way to legitimize their mandates vis-à-vis the international community (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

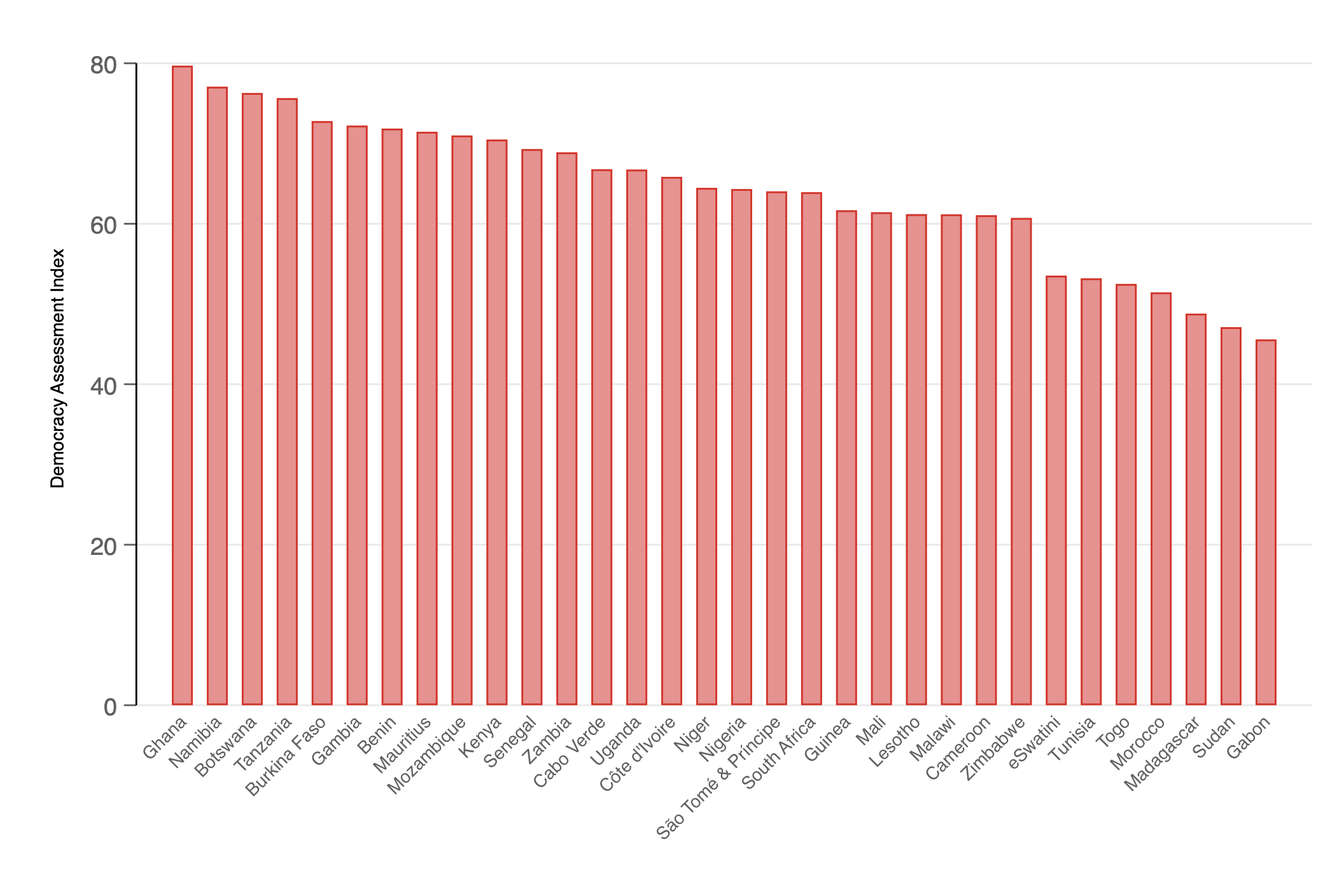

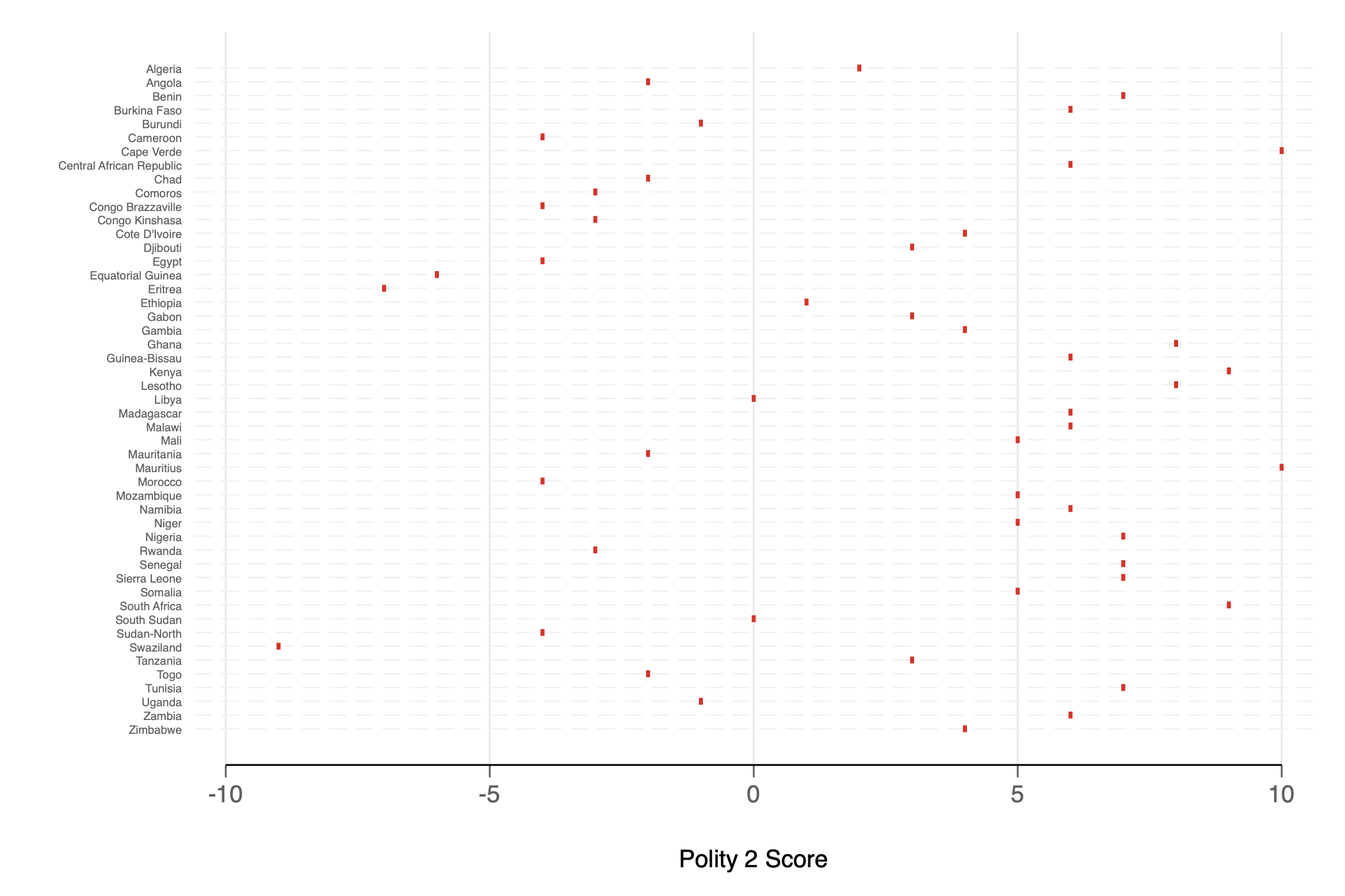

Democracy is a much broader term and, under these lenses, there is much more diversity across African governments, as shown in the Figure below, that uses data from the Center for Systemic Peace to classify countries on a scale from -10 to 10, with -10 being the most autocratic regime.

Figure 6.9: Autocracy-Democracy Index 2018: Polity 2 (Center for Systemic Peace, 2020)

Even using this scale is not enough to fully understand the spectrum of characteristics of African governments, and many times this can lead to critical issues. For instance, we must ask:

- Can democracy exist in Africa?

- What is the role of democracy in development?

- Can authoritarian regimes propel development?

To answer these questions, we first need to acknowledge that there have been many swings in the type of government regimes in Africa across time and that there are multiple realities across the continent. The following table contains some notes on the general political regime patterns in Africa. In class, we will develop these concepts further.

| Period | Context | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-colonial | Multiple tribes across the continent | Different levels of centralization. Early democracy |

| Colonial | Colonial governments | Preference to certain groups over others. “Big Men” (tribal chiefs) |

| Independence | Nationalism & Cold War | “Big Men” emerged. Unity and development as the primary concerns. Neo-patrimonial system. West vs. East competing for allies |

| 1990’s | End of Cold War | The West= political conditionality. Civil society demands. Government repression, patronage, and neo-patrimonialism. |

| 2000’s forward | China as a crucial actor | Most African countries have elections. Civil society demands. Government repression, patronage, and neo-patrimonialism. Governance. |

According to Ayittey (2006), native African institutions although different than the Western institutions, contained elements that required the population’s approval towards the king and the chiefs, with autocracy being the exception rather than the rule. This argument is supported by a recent book by David Stasavage that indicates that early democracy existed in many regions within Africa, with systems based on three motivations:

- Small-scale cooperation (remember that, because of the limited reach of the state, it was easier for members of the society to participate in councils and assemblies)

- It was a mechanism to learn what people were producing them and tax them accordingly.

- It served as a balance between how much rulers needed their ‘constituency’ and how much people could do without rulers. It was a consensual mechanism.

Although these systems had strengths and weaknesses, they showed signs of early democratic regimes. However, once colonizers arrived into these regions, they imposed a different system that, for the most part, did not adapt to the local institutions and instead imposed a system of hereditary chiefs.

This is one reason why Ayittey argues that adapting Western regimes will not work for Africa as they are artificial. Instead, he proposes to return to the African roots and heritage and build upon them. Under these native systems, consensus is preferred over a winner-takes-all system. With this, Ayittey argues that this would not entail imposing authoritarian regimes, but to impose democratic ones that are tailored to the needs of the African people, using a consensual approach. This position is similar to Nyerere’s in Tanzania.

However, there are some concerns about the application of this system, as it promotes one-party systems, with the claim that they promote stability. If the systems do not allow competition at other levels, it could become more authoritarian and prevent voices from being heard (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2020).

6.4 The Role of Institutions

Recently, we analyzed Ang’s argument on development and her criticism on the idea that history (institutions) will ‘determine’ the future of a country and society. In recent decades, institutions’ role and their importance as determinants of long-term development have received more attention. Some of the pioneers in this school of thought ar Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson and Simon Johnson (see, for instance, Acemoglu and Robinson (2012))

This has shifted the attention from arguments focused on geographic factors and the initial circumstances as drivers of development. Initially, geographic factors, on their own, were thought to be important determinants of long-term development. There is a considerable consensus in the field that this is not the case. These geographical characteristics were then argued to be associated with colonization patterns and the type of macro institutions established in certain regions.

However, as shown by Naritomi et al. (2012), it may be the case that geographic characteristics may serve to explain the local institutions that are relevant to explain intra-country differences and local patterns of development. The authors use Brazil’s case, a large country for which geography (distance to the equator) seems to explain the differences in income per capita. The authors use the resource booms that took place during the colonization period: sugar and gold and explore the types of institutions established in the country in geographical areas where these resources could be produced or extracted. The authors find that sugar production led to the unequal distribution of land whose effects remain nowadays. Municipalities whose origins are associated with gold production have worse governance practices.

These effects are similar to the results found by Dell (2010) in Peru, where a forced labor mining system in Peru (“Mita system”) implemented by the Spaniard colonizers between 1573 and 1812 is correlated with a contemporary lower consumption (of 25%) and prevalence of stunted growth in children (by 6%).

These results show that the channel throughout which geography may impact development is through its impact on the established institutions. In turn, historical institutions play a role in determining property rights enforcement, ethnic fractionalization, inequality, and public goods provision.

How do they impact development? What type of institutions are we referring to? When we talk about the effect of institutions on development, we will primarily look at the effects of governance, or state capacity. These are not the only institutions that matter for development, as other ones are also worth analyzing, such as property rights, strong judiciary, and financial institutions (an independent central bank, for instance).

According to Englebert (2000), the clash between pre- and post-colonial institutions may have had a strong effect on Africa’s development path. When looking at the mechanisms, Englebert argues that whenever there is a clash between institutions inherited from colonialism and pre-colonial institutions, institutions will be seen as less legitimate and will lead to a system closer to neo-patrimonialism. When these institutions are more compatible, the new institutions will seem less artificial and considered more legitimate by the local population. The state will be stronger and economic development will pursue. In this case, then, how institutions impact development in Africa is throughout the legitimacy (vertical and horizontal), they have among the population. When the state’s configuration does not seem legitimate, political elites will resort to neo-patrimonial policies and will invest little in improving governance and promoting the development of the territory.

In the meantime, Herbst (2000) argues that state capacity building depends on three aspects: the cost of increasing state capacity, the nature of the country’s boundaries (the territorial boundaries that were artificially set by the colonizers and that also serve as buffers of other institutions), and the design of state systems. Effectively, if the cost is higher than the benefit, no state capacity will be created. In that sense, Herbst concludes that African institutions reflect the environment and the historical forces and that the way leaders meet the challenges set by this context will determine the viability of strong African states.

6.5 Seminar Questions Module 2

- Pre-Colonial Africa and Trade of Enslaved Persons

- How does pre-colonial history in Africa compare to the history of other regions of the world? Develop your answer.

- How did the trade of enslaved persons contribute to the disintegration of kingdoms in Africa? What made it different from other slave trades in Africa and other regions across the world?

- Colonization

- Why were the borders the “most consequential part of the colonial state”? Was colonization different depending on the colonizer? If so, how?

- Many argue that colonization is still here, that the power division and colonization practices are still in place. Do you agree with that? If so, what real decolonization should look like?

- After independence

- How did colonization affect the political development of African countries?

- How did colonization affect the economic development of African countries?

- Conflict and development

- Why do you think there is little agreement about how natural resources are associated with conflict?

- How criminal activities serve the patrimonial system?

- Do you think that corruption can, up to a level, promote development? Please develop your answer

- Politics and development

- Taxation has been crucial across history to determine if democracy emerges. What would explain that democracy did not emerge after independence in African countries?

- Why would authoritarian systems may have an advantage over democratic systems when promoting development?

- The role of institutions

- How do institutions promote development? Use Robinson and Acemoglu’s argument explained in the podcast.

6.6 Activities Module 2

- We will have our first debate: Does history determines the development path of a society?

- We will examine our own positions about corruption: What would you do?

- We will discuss about what is democracy

- A challenge on ‘Institutions and Development’

6.7 Readings Module 2

6.7.1 Required Readings Module 2

Pre-colonial Africa and trade of enslaved persons

Nunn, Nathan (2008), “The Long-Term Effects of Africa’s Slave Trades”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123: 139-176.

Podcast: Conversations with Tyler- Nathan Nunn on the Paths to Development

Colonization and development

Michalopoulos, S. and Papaioannou, E. (2016), “The Long-Run Effects of the Scramble for Africa”, American Economic Review, Vol. 106(7). pp. 1802-1848.

Moss, T. and Resnick, D. (2018). African Development, 3rd. Ed. Boulder: Kynne Rienner- Chapter 2

After Independence

Moss, T. and Resnick, D. (2018). African Development, 3rd. Ed. Boulder: Kynne Rienner- Chapter 3

Please read the discourse of former president of Tanzania, Julious Nyerere, at the University of Zambia in 1966: The Dilemma of the Pan-Africanist

Conflict and development

Ross, M. (2004). “What Do We Know about Natural Resources and Civil War?”, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 41(3). pp. 337-356

Chabal, P. and Daloz, J-P. (1999). Africa Works: Disorder as Political Instrument. Oxford: James Currey- Chapter 6

Politics and development

Ayittey, G. (2006). Indigenous African Institutions, New York: Transnational Publishers. Read the Introduction

Please watch: Rocking your Priors Podcast with Dr. Alice Evans “The Decline & Rise of Democracy”: Professor David Stasavage. You can listen to the Podcast instead.

The role of institutions

- Podcast: - Rocking your Priors Podcast with Dr. Alice Evans “The Narrow Worridor”: Professor Daron Acemoglu.

6.7.2 Additional Readings and Resources Module 2

Pre-Colonial Africa and Trade of Enslaved Persons

- A less-than-five-minute reading: Williams, D.L. “Was slavery a ‘necessary evil’? Here’s what John Stuart Mill would say” The Washington Post (July 30, 2020)

- Ehret, Ch. (2014) . “Africa in World History before ca. 1440”, In Emmanuel Akyeampong, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn, James A. Robinson (eds) Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective, pp. 33-55. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Colonization and Development

- (Highly recommended): King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa - Documentary film based on the book of the same name by Adam Hochschild (1988). The film contains scenes with high levels of violence for sensitive viewers

Conflict and Development

- Moss, T. and Resnick, D. (2018). African Development, 3rd. Ed. Boulder: Kynne Rienner- Chapter 5

The role of institutions

- Englebert, P. (2000) “Pre-Colonial Institutions, Post-Colonial States, and Economic Development in Tropical Africa”. Political Research Quarterly. Vol. 53(1). pp: 7-36

- Herbst, J. (2000). “The Challenge of State-Building in Africa”. In Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Additional Sources

- Cheeseman, N. and Fisher, J. (2019). Authoritarian Africa. New York: Oxford University Press

- Dalton, John T. and Tin Cheuk Leung (2014), “Why is Polygyny More Prevalent in Western Africa? An African Slave Trade Perspective”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 63 pp. 599-632.

- Fenske, James and Namrata Kala (2015), “Climate and the Slave Trade”, Journal of Development Economics, 112: 19-32.

- Fenske, James and Namrata Kala (2016), 1807: Economic Shocks, Conflict and the Slave Trade, Working paper.

- Lipset, S. (1959), “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy”, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 53(1), pp. 69-105

- Przeworski, A. Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J-A. and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Whatley, Warren and Rob Gillezeau (2011), “The Impact of the Transatlantic Slave Trade on Ethnic Stratification in Africa”, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, Vol.101: pp. 571-576.

- Whatley, Warren C. (2014), “The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and the Origins of Political Authority in West Africa”, In Emmanuel Akyeampong, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn, James A. Robinson (eds) Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective, pp. 460-488. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Zhang, Yu and Shahriar Kibriya (2016), The Impact of the Slave Trade on Current Civil Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa, Working paper, Texas A&M University.

Terms and Definitions

Big-man politics: It is a political system where the politicians (Big men) keep power throughout the distribution of resources to certain sectors of the population. In return, politicians can rely on these persons to mobilize support for them (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

Neo-patrimonialism: System in which the patrons use state resources to secure the support of sectors of the population, based on a hierarchical/‘traditional’ way. This system works in an informal way within a formal structure.

Strong state: “Form of organized domination that delivers order and public goods” (Centeno, )

State capacity: “Organizational and bureaucratic ability to implement governing projects” (Centeno,). “The ability of states to plan and execute policies and to enforce laws cleanly and transparently” (Fukuyama, 2004). Preferred definition –> “The capacity of the state to actually penetrate civil society and to implement logistically political decisions throughout the realm.” (Mann, 1984)

Power (in the context of state capacity): “Ability to get others to do things that they might not have done otherwise.” (Centeno, ; Dahl, 1957).

Kinship norms are related to cousin marriage, clans, and co-residence that fostered social tightness, interdependence, and in-group cooperation↩︎

The specific argument was that with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the last ideological alternative to liberalism had been eliminated (He, of course, did not take the events in Tiananmen Square into account). The argument has been criticized for its Eurocentric approach, and it must be said that the entirety of the argument involved the creation of an effective state, the rule of law that binds the sovereign, and accountability. Fukuyama has updated his argument, focusing on the value of institutions.↩︎

Disclaimer: In some instances, ACLED records one single event that spread across different places as different events.↩︎

This is not to say that these countries do not face tensions and that the situation is not fragile, as there are many unresolved issues↩︎

The index was constructed following Stasavage’s self-assessment of democracy index, using data from the Round 7 of the Afrobarometer.↩︎