Chapter 6 Conspiracy and Fact

6.1 To-do list (Week 8)

Reading: Operation Denver

Reading: You are not so smart

6.2 In-class survey

- Take the survey “Why Aren’t They Telling Us?” on Blackboard

6.2.1 Discussion

- Why do you believe or not believe?

- The common theme is “the government is hiding something from us” and “critical thinkers” should not be fooled by these conspiracies.

6.2.3 Context

This year (2019) is 50th aniversary of Apollo, but we still have people who believe moon landing is just a hoax. Here is a clip by Vice News showing the story of three moon truthers. In July 2019, over 1 million people signed up to storm area 51, which supposedly have remains of aliens.

6.2.4 Area 51

- What are the story about area 51? What does it have to do with aliens?

- A look back at 1989 Bob Lazar interview; it started new UFO conversations.

- Why I believe in UFOs, and you should too.

- Some books: The 37th Parallel: The Secret Truth Behind America’s UFO Highway, by Ben Mezrich. Area 51: An Uncensored History of America’s Top Secret Military Base, by Annie Jacobsen.

6.2.5 Three parts

- “birthplace of overhead espionage”

association with aliens

- A look back at 1989 Bob Lazar interview; it started new UFO conversations.

- On June 20, 2019, the libertarian-flavored podcast The Joe Rogan Experience.

- John Lear’s letter.

UFO

6.3 Why do we believe certain things?

- What is the yardstick for you to believe in certain things? Small group discussion.

6.3.1 What is a conspiracy?

- Characteristics of a conspiracy?

- secrecy

- sinister (or at least objectionable) aims

- unofficial

6.3.2 Some conspiracies that are proven true

Although there is a layer of normative judgement behind conspiracy, this does not necessarily mean all conspiracy theories are wrong. Here are some examples: 7 bizarre conspiracy theories that are actually true, 10 Secret U.S. Government Operations, Revealed, and 12 Crazy Conspiracy Theories That Actually Turned Out to Be True.

It is also intellectually lazy to label non-official explanations as conspiracy theories. Even for those that are commonly labeled as conspiracy theories, it is not enough to reject them simply because many people claim they are false. From the perspective of argument and critical thinking, we need to discuss what they are and what are the reasons for us not to believe them.

Relatedly, I do not mean to suggest the government is telling us everything. In particular, many governments around the global were and are engaged in covert actions that they do not wish citizens and outsiders to know. Here are some best books on Covert Action, which covers several different countries. Here are some archives by the National Security Archives.

6.3.3 Conspiracy and disinformation

Here is an interesting story of how KGB and Stasi used AIDS disinformation.

6.3.4 Covert operations

MK-Ultra: here is clip by History.

COINTELPRO: here is a list of different activities at the websit of FBI. Here is an NYTimes’ interview. And here is a blog by allthatsinteresting.

6.4 Conspiracy theories and critical thinking

Many conspiracy theory endorsers “are also passionate advocates for critical thinking education.”

The powerful elite needs to dumb down the general public, “by suppressing the development of critical thinking capacities among the unwashed masses.”

6.4.1 What’s your take of conspiracy theories?

Here is a “dismissive” take in not engaging in a conversation with people who choose to be deliberately stupid. The scientist went further to say that he prefer to not being a “pig wrestler.” Personally, I favor the emphasis that the world is full of interesting and meaningful things to explore.

The default skepticism about conspiracy theories by most academics.

6.4.2 Default skepticism

Default skepticism can be summe up this way:

- the grander the conspiracy that is required, the less likely it is that it’s true.

The grandness is not well-defined, but typically can be accounted by how many people and how long to keep the conspiracy secret and how many layers of social and institutional structures are implicated. Hence, compare the following examples:

- the members of a political party to leak negative information about an opposition candidate

- pharmaceutical companies to hide the cure for cancer for the past twentyTfive years

- government and law enforcement officials to hide the existence of a crashed alien spacecraft in Area 51 for the past 60 years

- But of course the grandess is not an argument against conspiracy theories’ nature of implausibility. This is purely a judgement/conclusion, and we want to understand the reasons that lead to this conclusion.

6.4.3 The reasons: illustrated via the moon landing hoax theory

The theory’s plausible aspects:

- It’s plausible that NASA didn’t have the time or technological ability to fulfill John F. Kennedy’s promise that he made in a speech in 1961 to put a man on the moon before the end of the decade.

- It’s plausible that the video of astronauts on the moon could be reproduced on a sound stage.

- And there’s no doubt that NASA felt enormous pressure to pull this off, given the state of the Cold War with the Soviet Union and the political costs of either a failed mission or of the Soviets getting there first.

That said, these are not important in terms of evaluating the theory. What we are or should be interested in are the implausible aspects of the theory. That is,

- what would have to be true if the theory is right and the landings were faked, and the conspiracy not only to fake the landings, but to keep it secret from the general public, was in fact successfully maintained for over 40 years, up to the present day.

6.4.4 Another illustration via 9/11

This is a quote from Skeptical Inquirer magazine (summer 2011) about controlled demolition.

- I found it easy to dismiss the demolition theories without requiring analytical refutation. These theories introduce far greater problems to address than anything they purport to solve. It seems the “mastermind” would almost certainly have to be the President of the United States. What would we do to such a President if he were found out? Clearly he would have to believe that absolute secrecy could be maintained forever. We can’t even keep secrets in the CIA! Many people would have to be involved over an extended time period: demolition experts, hijackers, FBI and Interpol investigators, etc. What if one of the WTC aircraft hijackings had been thwarted by the passengers as in the case of Flight 93? One of the towers would still be standing with demolitions evidence that would have to be removed. Even a flight cancellation or a delay would have created havoc. What if WTC 7 hadn’t caught fire? Certainly this could not have been guaranteed. Would they have proceeded with the demolition? What if the demolition triggers failed due to damage from the aircraft? The list could go on for pages. All of this so we could go to war in Afghanistan? Give me a break!

Therefore, Kevin deLaplante argues:

The premise that underwrites this line of reasoning is a general one, it’s not specific to 9/11 theories. The idea is this: For it to be rational to try and implement a grand conspiracy of this sort, you would need enormous confidence that a complex series of operations would go off without a hitch, that information about the conspiracy could be contained indefinitely, and that the behavior of dozens, hundreds, maybe thousands of a people can be controlled with a high degree of certainty.

And the objection is that, given what we know about human nature and the functioning of complex social institutions, and the difficulty of predicting the success of complex operations like the ones we’re talking about here, we just don’t have any reason to think this level of control and certainty is possible. As the conspiracy scales in size and complexity, the more likely it is to fail, and less likely that rational people would evenattempt it.

6.4.5 Mind control

Now, the above reasonings lead to the debate about the plausibility of mind control.

There are some plausible mind control methods:

- media as a propaganda tool for manipulating public opinion and behavior

- education system as a means of public manipulation

- technology to track our internet activity and shopping behavior and online conversations.

There are less plausible ones:

- government and corporations are adding toxins to our food and water supply with the express aim of altering our brain chemistry to make us more docile and apathetic and more susceptible to manipulation

- spraying chemicals from airplanes

- electromagnetic radiation that we’re constantly bathed in can be manipulated to alter brain states

6.4.6 How the issue of mind control change the debate

- logical cirularity

- dis-informers

6.5 Falsifiability

There are a couple of ways that make it theory unfalsifiable. First, making only vague predictions.

Second, revising theories to accomodate potentially falsifying evidence.

6.5.1 The example of 9/11

Let me begin by introducing David Ray Griffin’s theory that the twin towers came down due to a controlled demolition (here is a clip of his interview). Students who are interested in stories of other activists can also watch this documentary: New World Order. Here is a trailer. These people dispute the mainstream (government) explanation of the 9/11 attack and regard themselves as involved in the 9/11 Truth Movement.

6.5.2 Additional resources

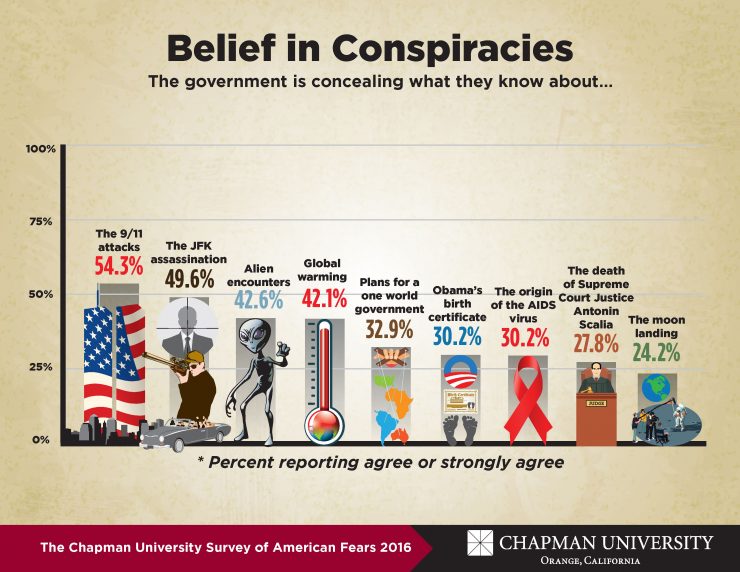

Here is an introduction of America’s 10 most popular conspiracy theories. Here is another one: 10 of the world’s most enduring conspiracy theories.

- 9/11: Here is a short introduction of the 9/11 conspiracy by BBC.

- JFK: Note this “A 2003 ABC News poll found that 70% of Americans believe Kennedy’s death was the result of a broader plot”, pointed out here.

- Alien: Over 1 million people signed up to storm area 51 this July 2019, which was originally meant as a joke. Here is a report by the Guardian, which quotes “If we naruto run, we can move faster than their bullets. Lets see them aliens.”

- Global warming: Here is an interesting debunking and rebunking blog.

- One world government: There are several versions. For instance, the Bilderberg Group, the bedunking blog, the Rothschild, and Illuminati and the New World Order.

- Obama: BBC’s report.

- HIV: Here is a list by Slate.

- Scalia: 10 theories of Scalia’s death.

- Moon landing: 50 years after Apollo, conspiracy theorists are still howling at the ‘moon hoax’.

6.6 Confirmation bias

P.C. Wason’s number sequence game. Here is a New York Times’ interactive puzzle.

Wason’s Four-Card Task. Vote and explain.

6.7 The backfire effect

6.8 How do we reason

There is a gap between how our normative theories say we should reason, and how we in fact reason. [from CTA]

Why do we believe things that aren’t true? | Philip Fernbach.

6.9 Acknowledgement

This section takes a lot of materials from Kevin deLaplante’s critical thinking course and from You Are Not so Smart.