Chapter 3 Bureaucracy (Week 3-4)

3.1 Discussion questions

What are China’s strategic intentions? Did any of the readings change your answers from last week?

What is Economy (2018)’s argument? How does it differ from last week’s readings?

What have you learned from Goldstein (2020)? What are the policy implications?

What do you think the Chinese foreign policy making process is like? (*)

3.2 Discussion questions (Week 4)

What is Weiss & Wallace (2021)’s argument? How does China pick and join international institutions? And what are the implications and challenges for the rest of the world, for Europe?

Zhao (2020): What are the key players and institutions in the Chinese foreign policy making process? Check the diagram below and see if you can expound on the roles of each institutions.

What are China’s strategic priorities? How important is Europe to China? (*)

America’s New Great-Power Competition with China | Policy Stories

3.3 The leadership under Xi Jingping

Economy (2018) offers a very different take than Weiss (2019). Her main arguments revolve around China’s recent efforts in projecting economic power (e.g BRI, economic coercion (see also Hoover Institution’s China’s global sharp power project)) and exporting political values (e.g. surveillance technology, closed internet, Confucius Institutes). Therefore, China is an “illiberal state seeking leaderhsip in a liberal world order” (p.61).

Building on these reasonings, she argues that China poses a “values-based challenge” to the U.S. and recommend that the U.S. should take a more restrictive approach to China via “maintaining a strong military presence in the Asia-Pacific but also demonstrating a continued commitment to free trade and democracy” (p.70). Note that similar policy recommendations are also proffered by Meirsheimer (2019). Some of the policy recommendations are still being followed by the Biden adminstration (e.g. strengthening the Quad in the Indo-Pacific region). Looking ahead, Economy believes that democratic transition in China is still possible (e.g. via economic crisis) and that China’s could overreach abroad, encounter backlashes, which in turn would undermine Xi’s authority at home.

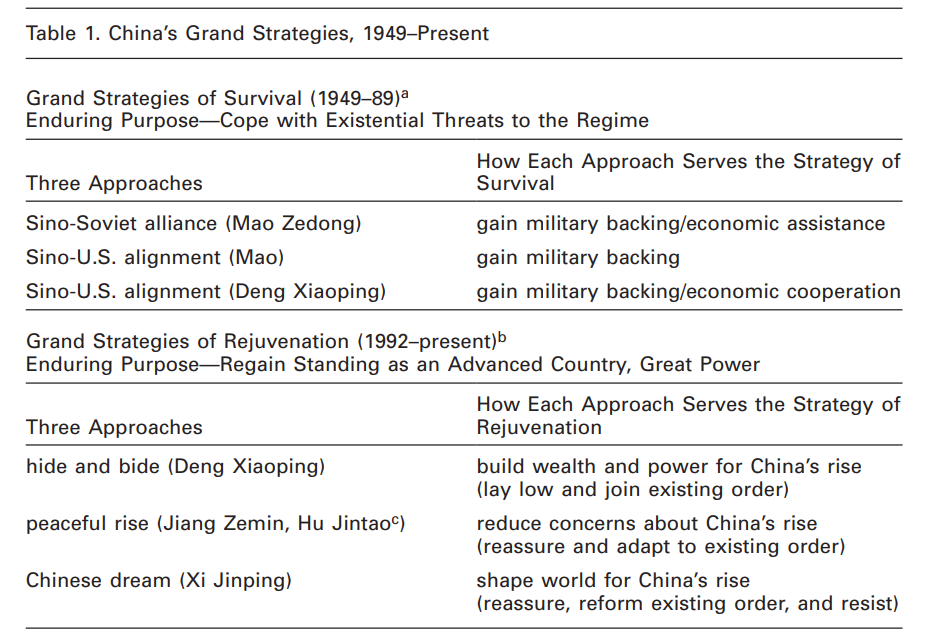

Goldstein (2020) addresses the grand strategy question: Has Xi broken away from China’s “broadly cooperative approach” given the recent more assertive foreign policy? He argues that Xi’s approach is not a fundamental departure. In pursuing national rejuvenation, China has taken three approaches since the end of the Cold War.

Let us unpack a bit. Goldstein situates China’s grand strategy along three main influences.

- An ideological commitment to fulfilling the nationalist dream of rebuilding a prosperous and powerful China

- A strong institutional self interest in preserving the CCP’s leading role in an authoritarian polity that they deem necessary for realizing the nationalist goal

- Changes in China’s capabilities relative to other states and other states’ reactions to China’s international behavior

— Goldstein (2020, 167-168)

In this regard, Xi’s strategy is not a fundamental departure from previous leaderships. The end goal still revolves around building a conducive international environment for China to realize the nationalist dream. The efforts of trying to alleviate concerns about China’s rise and to (re)build the reputation as a responsible player follows the traditions since the end of the Cold War. However, there are also distinctive features of Xi’s strategy. Instead of adapting to the existing international order and institutions, China seeks to play a more active role in reforming the order. But it should be noted that this is a reformist, not revisionist, strategy (as Drezner 2019 also points out). It should also be noted that the reform will be selective and focusing solely on the economic order. This is understandable given the second influence mentioned above.

The other distinctive feature is to more resolutely resist challenges to China’s core interests. As Goldstein points out, “Xi, however, has not only been less diffident in staking out China’s positions on core interests; he has also devoted more attention and resources to ensuring that China has the capabilities to defend them” (Goldstein 2020, 187). Although this feature (and the other two) has its historical roots in the 1996-2008 era, “Xi has acted on its imperatives more openly, consistently, and with a vigor absent under his predecessors” (Goldstein 2020, 179).

This strategy and its implementation have reignited the concerns about China’s rise and prompted countries to reevaluate their China policies. Importantly, the policy has encouraged China’s key economic partners to reconsider their economic engagement with China. See, for instance, this discussion After Merkel: Germany’s Approach to China. And here: Germany’s post-election China policy: it’s not what, it’s how.

As such, Goldstein argues that China is venturing into a “more difficult and uncertain path.”

3.3.1 Why the rush?

The above discussions begs the question concerning why Xi is on such a rushed timeline. Blanchette (2021) addresses this question. Specifically, Xi

“sees a narrow window of ten to 15 years during which Beijing can take advantage of a set of important technological and geopolitical transformations, which will also help it overcome significant internal challenges.”

— Blanchette (2021, 10)

The “geopolitical, demographic, economic, environmental, and technological” challenges include

- a new era of multipolarity with accelarated decline of the West

- an aging and shrinking population of China

- slowdown of Chinese economy (with flagging productivity)

- advances in new technologies

Blanchette argues that these structural challenges are further compounded by Xi’s leadership style (which he categorizes as “paranoid”) which inflates threat perception. In contrast to Mao and Deng’s strategic patience (resulting from a profound understanding of China’s relative fragility and the import of careful nuanced strategies), Xi “has positioned himself for a 15-year race” (p.18). Given this rushed time line, Xi will have to abandon the invisible hand of the market and shift to a system that relies more on state actors. All these boil down to whether China’s industrial policy (Made in China 2015, Internet Plus, and the 14th Five-Year Plan) will be successful or not in the next decade.

3.4 Additional resouces

How President Xi Jinping is transforming China at home and abroad

Elizabeth Economy Expounds on U.S. Foreign Policy Relations with China | Policy Briefs

Is A Shift In China’s Foreign Policy Underway, And Will It Work? | CNA Correspondent 1:30-8:30 11:40-16

‘Wolf Warrior diplomacy’: Chinese foreign policy alienates global partners

Course correction: China’s shifting approach to economic globalization

Is U.S. Foreign Policy Too Hostile to China? Foreign Affairs Asks the Experts

3.5 Week 4 video

3.6 The decision making process

Here is a graph of the core structure. Note that I do not include the Foreign Affairs Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Foreign Affairs Office of the State Council. As Zhao (2020) notes, the former plays a role in “foreign policy consultation and parliamentary diplomacy.” The latter “is primarily an administrative setup to supervise local foreign affairs offices and coordinate routine matters involving foreign affairs for the top leaders.”

3.7 Domestic politics

Check Sun (2017) for the evolving role of MFA and Wu (2021) for FAO.

See below for notes of the acronyms. I also include their Chinese names for your reference.

PSC: Politburo Standing Committee (政治局常委)

FAC: Central Foreign Affairs Commission (中央外事工作委员会). Established in 2018 to replace the Central Foreign Affairs Leading Small Group (FALSG, 中央外事领导小组).

NSLSG: Central National Security Leading Small Group (中央国家安全领导小组)

FAO: Foreign Affairs Office (中央外事办公室)

ILD: International Liaison Department (中联部)

PD: Publicity Department (中宣部)

MFA: Ministry of Foreign Affairs (外交部)

MOC: Ministry of Commerce (商务部)

GSD: General Staff Department (总参). Disbanded in 2016 amid the military reform and replaced by the Joint Staff Department (联合参谋部).

3.8 China and LIO

Recall that Goldstein (2020) talks about how the change of relative power shapes China’s attitude toward LIO. Weiss & Wallace (2021), however, place a higher premium on the role of domestic politics. They argue there are four unique characteristics of current CCP rule that puts the country at odds with LIO: state capitalism, opposition of individual political rights and civil society, “rule by law”, and nativism. As such, while China has been embracing economic (embedded) liberalism and has a mixed record in liberal institutionalism, it is fundamentally in conflict with political liberalism. Note that a careful distinction is drawn here: post-Mao China has not sought to export a universal ideology, which is also emphasized in Weiss (2019).

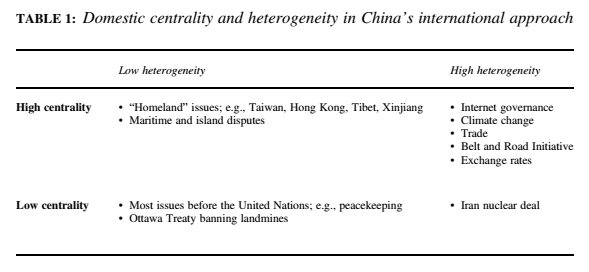

Against this backdrop, China has been carefully selecting and joining in parts of the LIO, depending on the centrality (salience) of the issue and heterogeneity (division) of domestic attitudes. They then proceed to discuss China’s strategies toward the different issues shown below.

What are the implications here? What are the potential ways forward for international order? They point out two possible avenues: a more restricted (demanding) version of LIO that exclude illiberal states or a return to more Westphalian oriented version that are domestically less intrusive.

3.9 Additional resources

Is China’s economic model broken? | FT

The EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investments (CAI): a piece of the puzzle.

The Poison Frog Strategy Preventing a Chinese Fait Accompli Against Taiwanese Islands

How should Taiwan, Japan, and the United States cooperate better on defense of Taiwan?

China Hurries to Burn More Coal, Putting Climate Goals at Risk

America Is Turning Asia Into a Powder Keg The Perils of a Military-First Approach

The Inevitable Rivalry America, China, and the Tragedy of Great-Power Politics

The New Cold War America, China, and the Echoes of History

Azerbaijan’s Aliyev is a Strategic Liability, Not an Asset, which talks about how some Western countries having been ignoring Aliyev’s corruption and repression