3 Research Design

Research design refers to the plan to collect information to address your research question. It covers the set of procedures that are used to collect your data and explain how your data will be analyzed. Your research plan identifies what type of design you are using. Your plan should make clear what your research question is, what theory or theories will be considered, key concepts, your hypotheses, your independent and dependent variables, their operational definitions, your unit of analysis, and what statistical analysis you will use. It should also address the strengths and weaknesses of your particular design. The major design categories for scientific research are experimental designs and observational designs. The latter is sometimes referred to as a correlational research design.

3.1 Overview of the Research Process

Often scholars rely on data collected by other researchers and end up, de facto, with the research design developed by the original scholars. But if you are collecting your own data this stage becomes the key to the success of your project and the decisions you make at this stage will determine both what you will be able to conclude and what you will not be able to conclude. It is at this stage that all the elements of science come together. We can think of research as starting with a problem or a research question and moving to an attempt to provide an answer to that problem by developing a theory. If we want to know how good (empirically accurate) that theory is we will want to put it to one or more tests. Framing a research question and developing a theory could all be done from the comforts of your backyard hammock. Or, they could be done by a journalist (or, for that matter, by the village idiot) rather than a scientist. To move beyond that stage requires more. To test the theory, we deduce one or more hypotheses from the theory, i.e., statements that should be true if the theory accurately depicts the world. We test those hypotheses by systematically observing the world—the empirical end of the scientific method. It requires you to get out of that hammock and go observe the world. The observations you make allow you to accept or reject your hypotheses, providing insights into the accuracy and value of your theory. Those observations are conducted according to a plan or a research design.

3.2 Internal and External Validity

Developing a research design should be more than just a matter of convenience (although there is an important element of that which we will discuss at the end of this chapter). Not all designs are created equally and there are trade-offs we make when opting for one type of design over another. The two major components of an assessment of a research design are its internal validity and its external validity. Internal validity basically means we can make a causal statement within the context of our study. We have internal validity if, for our study, we can say our independent variable caused our dependent variable. To make that statement we need to satisfy the conditions of causality we identified previously. The major challenge is the issue of spuriousness. We have to ask if our design allows us to say our independent variable makes our dependent variable vary systematically as it changes and that those changes in the dependent variable are not due to some third or extraneous factor, often called an ommitted variable. It is worth noting that even with internal validity, you might have serious problems when it comes to your theory. Suppose your hypothesis is that being well-fed makes one more productive. Further suppose that you operationalize “being well-fed” as consuming twenty Hostess Twinkies in an hour. If the Twinkie eaters are more productive than those who did not get the Twinkies you might be able to show causality, but if your theory is based on the idea that “well-fed” means a balanced and healthy diet then you still have a problematic research design. It has internal validity because what you manipulated (Twinkie eating) affected your dependent variable, but that conclusion does not really bring any enlightenment to your theory.

The second basis for evaluating your research design is to assess its external validity. External validity means that we can generalize the results of our study. It asks whether our findings are applicable in other settings. Here we consider what population we are interested in generalizing to. We might be interested in adult Americans, but if we have studied a sample of first-year college students then we might not be able to generalize to our target population. External validity means that we believe we can generalize to our (and perhaps other) population(s). Along with other factors discussed below, replication is a key to demonstrating external validity.

3.3 Major Classes of Designs

There are many ways to classify systematic, scientific research designs, but the most common approach is to classify them as experimental or observational. Experimental designs are most easily thought of as a standard laboratory experiment. In an experimental design the researcher controls (holds constant) as many variables as possible and then assigns subjects to groups, usually at random. If randomization works (and it will if the sample size is large enough, but technically that means infinite in size), then the two groups are identical. The researcher then manipulates the experimental treatment (independent variable) so that one group is exposed to it and the other is not. The dependent variable is then observed. If the dependent variable is different for the two groups, we can have quite a bit of confidence that the independent variable caused the dependent variable. That is, we have good internal validity. In other words, the conditions that need to be satisfied to demonstrate causality can be met with an experimental design. Correlation can be determined, time order is evident, and spuriousness is not a problem—there simply is no alternative explanation.

Unfortunately, in the social sciences the artificiality of the experimental setting often creates suspect external validity. We may want to know the effects of a news story on views towards climate change so we conduct an experiment where participants are brought into a lab setting and some (randomly selected) see the story and others watch a video clip with a cute kitten. If the experiment is conducted appropriately, we can determine the consequences of being exposed to the story. But, can we extrapolate from that study and have confidence that the same consequences would be found in a natural setting, e.g., in one’s living room with kids running around and a cold beverage in your hand? Maybe not. A good researcher will do things that minimize the artificiality of the setting, but external validity will often remain suspect.

Observational designs tend to have the opposite strengths and weaknesses. In an observational design, the researcher cannot control who is exposed to the experimental treatment; therefore, there is no random assignment and there is no control. Does smoking cause heart disease? A researcher might approach that research question by collecting detailed medical and lifestyle histories of a group of subjects. If there is a correlation between those who smoke and heart disease, can we conclude a causal relationship? Generally the answer to that question is ``no", because any other difference between the two groups is an alternative explanation (meaning that the relationship might be spurious). For better or worse, though, there are fewer threats to external validity (see below for more detail) because of the natural research setting.

A specific type of observational design, the natural experiment, requires mention because they are increasingly used to great value. In a natural experiment, subjects are exposed to different environmental conditions that are outside the control of the researcher, but the process governing exposure to the different conditions arguably resembles random assignment. Weather, for example, is an environmental condition that arguably mimics random assignment. For example, imagine a natural experiment where one part of New York City gets a lot of snow on election day, whereas another part gets almost no snow. Researchers do not control the weather, but might argue that patterns of snowfall are basically random, or, at the very least, exogenous to voting behavior. If you buy this argument, then you might use this as natural experiment to estimate the impact of weather conditions on voter turnout. Because the experiment takes place in natural setting, external validity is less of a problem. But, since we do not have control over all events, we may still have internal validity questions.

3.4 Threats to Validity

To understand the pros and cons of various designs and to be able to better judge specific designs, we identify specific threats to internal and external validity. Before we do so, it is important to note that a (perhaps ``the") primary challenge to establishing internal validity in the social sciences is the fact that most of the phenomena we care about have multiple causes and are often a result of some complex set of interactions. For examples, \(X\) may be only a partial cause of \(Y\), or \(X\) may cause \(Y\), but only when \(Z\) is present. Multiple causation and interactive affects make it very difficult to demonstrate causality, both internally and externally. Turning now to more specific threats, Table 3.1 identifies common threats to internal validity and Table 3.2 identifies common threats to external validity.

Figure 3.1: Common Threats to Internal Validity

Figure 3.2: Common Threats to External Validity

3.5 Some Common Designs

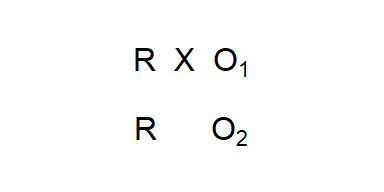

In this section we look at some common research designs, the notation used to symbolize them, and then consider the internal and external validity of the designs. We start with the most basic experimental design, the post-test only design Figure (fig:post). In this design subjects are randomly assigned to one of two groups with one group receiving the experimental treatment.1 There are advantages to this design in that it is relatively inexpensive and eliminates the threats associated with pre-testing. If randomization worked the (unobserved) pre-test measures would be the same so any differences in the observations would be due to the experimental treatment. The problem is that randomization could fail us, especially if the sample size is small.

Figure 3.3: Post-test Only (with a Control Group) Experimental Design

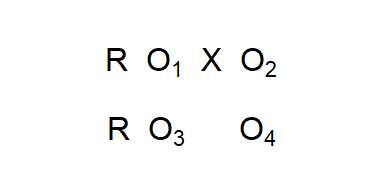

Many experimental groups are small and many researchers are not comfortable relying on randomization without empirical verification that the groups are the same, so another common design is the Pre-test, Post-test Design (Figure (fig:prepost)). By conducting a pre-test, we can be sure that the groups are identical when the experiment begins. The disadvantages are that adding groups drives the cost up (and/or decreases the size of the groups) and that the various threats due to testing start to be a concern. Consider the example used above concerning a news story and views on climate change. If subjects were given a pre-test on their views on climate change and then exposed to the news story, they might become more attentive to the story. If a change occurs, we can say it was due to the story (internal validity), but we have to wonder whether we can generalize to people who had not been sensitized in advance.

Figure 3.4: Pre-test, Post-Test (with a Control Group) Experimental Design

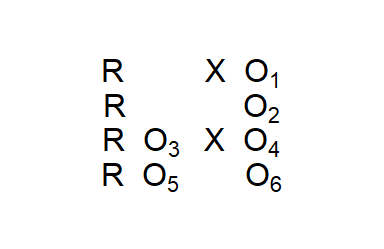

A final experimental design deals with all the drawbacks of the previous two by combining them into what is called the Solomon Four Group Design (Figure 3.5). Intuitively it is clear that the concerns of the previous two designs are dealt with in this design, but the actual analysis is complicated. Moreover, this design is expensive so while it may represent an ideal, most researchers find it necessary to compromise.

Figure 3.5: Solomon Four Group Experimental Design

Even the Solomon Four Group design does not solve all of our validity problems. It still likely suffers from the artificiality of the experimental setting. Researchers generally try a variety of tactics to minimize the artificiality of the setting through a variety of efforts such as watching the aforementioned news clip in a living room-like setting rather than on a computer monitor in a cubicle or doing jury research in the courthouse rather than the basement of a university building.

Observational designs lack random assignment, so all of the above designs can be considered observational designs when assignment to groups is not random. You might, for example, want to consider the affects of a new teaching style on student test scores. One classroom might get the intervention (the new teaching style) and another not be exposed to it (the old teaching style). Since students are not randomly assigned to classrooms it is not experimental and the threats that result from selection bias become a concern (along with all the same concerns we have in the experimental setting). What we gain, of course, is the elimination or minimization of the concern about the experimental setting.

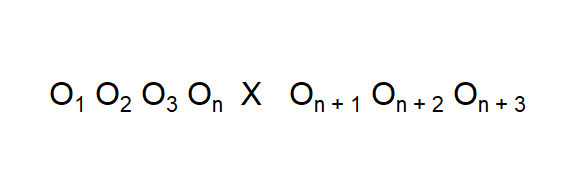

A final design that is commonly used is the repeated measures or longitudinal research design where repeated observations are made over time and at some point there is an intervention (experimental treatment) and then subsequent observations are made (Figure 3.6). Selection bias and testing threats are obvious concerns with this design. But there are also concerns about history, maturation, and mortality. Anything that occurs between \(O_n\) and \(O_{n+1}\) becomes an alternative explanation for any changes we find. This design may also have a control group, which would give clues regarding the threat of history. Because of the extended time involved in this type of design, the researcher has to concerned about experimental mortality and maturation.

Figure 3.6: Repeated Measures Experimental Design

This brief discussion illustrates major research designs and the challenges to maximizing internal and external validity. With these experimental designs we worry about external validity, but since we have said we seek the ability to make causal statements, it seems that a preference might be given to research via experimental designs. Certainly we see more and more experimental designs in political science with important contributions. But, before we dismiss observational designs, we should note that in later chapters, we will provide an approach to providing statistical controls which, in part, substitutes for the control we get with experimental designs.

3.6 Plan Meets Reality

Research design is the process of linking together all the elements of your research project. None of the elements can be taken in isolation, but must all come together to maximize your ability to speak to your theory (and research question) while maximizing internal and external validity within the constraints of your time and budget. The planning process is not straightforward and there are times that you will feel you are taking a step backwards. That kind of ``progress’’ is normal. Additionally, there is no single right way to design a piece of research to address your research problem. Different scholars, for a variety of reasons, would end up with quite different designs for the same research problem. Design includes trade-offs, e.g., internal vs. external validity, and compromises based on time, resources, and opportunities. Knowing the subject matter – both previous research and the subject itself – helps the researcher understand where a contribution can be made and when opportunities present themselves.

3.7 Study Questions

- Observational designs generally have higher ________ validity and lower ________ validity compared to experimental designs. Why?

- Define spuriousness, also known as omitted variable bias.

- Why are randomized experiments being used more and more in political science?

The symbol R means there is random assignment to the group. X symbolizes exposure to the experimental treatment. O is an observation or measurement.↩