Chapter 18 The Effects of the Situation

Why do people who know better do foolish things? Why do good people do things that seem callous, or even immoral? One answer is that they don’t really know better, or that they really aren’t as moral as they once seemed. Another answer is that maybe they wouldn’t have done those things had they not been in their respective situations. We’ll see experiments that show that situations can somehow lead people to do things they would never otherwise do.

18.1 The Fundamental Attribution Error

There are two kinds of explanations of human behavior. First, we can explain a person’s behavior by appealing to internal causes, like desires, beliefs, and character states. On the other hand, there are external causes, features of the situation the person is in at the time. It should be no surprise to anyone that both of these causes are at work whenever we act in a particular situation. When we underestimate the role that the external causes play, we commit what psychologists call the fundamental attribution error.

18.2 Experiments

Here are a few of the experiments that show the various ways that situations affect behavior

18.2.1 Game Show

In a 1977 study, subjects were assigned to be either questioners or contestants. The questioners were tasked to write challenging general knowledge questions and then test the contestants with them. Afterwards, both the questioner and the contestant were asked to rate the general knowledge of themselves and the other person. Questioners were encouraged to ask difficult questions from their own background knowledge, which gave them a significant advantage. As one would expect given the situation, the questioners were able to ask question that the contestants could not answer. Interestingly, both the questioner and the contestant rated the questioner as more intelligent than the contestant. (Ross, Amabile, and Steinmetz 1977)

18.2.2 Good Samaritan Study

John Darley and Daniel Batson recruited seminary students for a study that was purportedly on religious education. The subjects first completed some personality surveys, they were then told to go to another building to continue the study. Some subjects were told they would be giving a talk on job opportunities for seminary graduates, and others were told they would be giving a talk on the parable of the Good Samaritan. Another variable in the study was the “hurry condition.” The subjects were divided into three further groups that were told:

High-hurry: “Oh, you’re late. They were expecting you a few minutes ago.”

Intermediate-hurry: “The assistant is ready for you, so please go right over.”

Low-hurry: “It’ll be a few minutes before they’re ready for you, but you might as well head on over. If you have to wait over there, it shouldn’t be long.”

They were given directions and a map to the other building. On the way there, they encountered a man who was slumped over in a doorway, not moving, with his head down and eyes closed. As they passed by, the person would cough twice and groaned. The subjects were rated on whether, and to what degree, they helped the person.

40% of the subjects offered some help to victim. 63% in the low-hurry group helped, 45% of the medium-hurry group, and 10% of the high-hurry group. A person who is not in a hurry may very well stop to help. A person who is in a hurry is very likely to just keep going. Even those who were in a hurry and were going to talk about the Good Samaritan were very likely to not help. The researchers reported that some students on their way to talk about the Good Samaritan literally had to step over the victim to hurry on their way.

18.2.3 Helping Studies

In 1964, Kitty Genovese was stabbed to death in front of an apartment building in New York City. The New York Times reported that 38 people witnessed the attack, yet no one called the police or came to her aid. (Gansberg 1964) Even though the original story has been shown to be false in some important details, it prompted some important psychological research into what is called “bystander apathy,” the theory that people are less likely to offer help when there are other people present.14

John Darley and Bibb Latané hypothesized that the presence of other onlookers would incline people to not intervene for several reasons:

- The responsibility to intervene was diffused among the observers.

- Any blame for not intervening was also diffused among the observers.

- When an observer cannot see the reactions of other observers, it was possible that someone had already acted.

Test subjects were placed in individual rooms, where they were told that they would participate in a discussion of problems in college life. They were told that they were in a group of a certain size, and would communicate electronically with microphones and headphones to the other participants, who were also in individual rooms. Each person would have two minutes to speak, and while they were speaking, all other microphones would be off. (Actually, all of the other “participants” were recordings.) The first person to speak talked about his difficulty adjusting, specifically mentioning that he was prone to siezures. As he talked, he became louder and more incoherent, saying,

I-er-um-I think I-I need-er-if-if could-er-er-somebody er-er-er-er-er-er-er give me a liltle-er-give me a little help here because-er-I-er-I’m-er-er- h-h-having a-a-a real problem-er-right now and I-er-if somebody could help me out it would-it would-er-er s-s-sure be-sure be good . . . because- er-there-er-er-a cause I-er-I-uh-I’ve got a-a one of the-er-sei—er-er-things coming on and-and-and I could really-er-use some help so if somebody would-er-give me a little h-help-uh-er-er-er-er-er c-could somebody-er-er-help-er-uh-uh-uh (choking sounds). . . . I’m gonna die-er-er-I’m . . . gonna die-er-help-er-er-seizure-er-[chokes, then quiet].

The experimenter began timing the subject’s response time from the beginning of the victim’s speech. Some subjects thought that they were in a two-person group, others in a three-person group, and the rest in a six-person group. Here are the results of people reporting by the end of the victim’s message:

| Group size | % responding | Time to respond in seconds |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 85 | 52 |

| 3 | 62 | 93 |

| 6 | 31 | 166 |

Notice that the larger the group, not only were the subjects less likely to report at all, but they were slower to report when they did. Every subject in the two-person groups eventually reported, some after the victim finished his message.

There are reasons that would explain this behavior. First, since we can’t see or hear wha the other people are doing (or, more importantly, _not_doing), we tend to assume that someone else has already intervened. The second reason is something called diffusion of responsibility. If there is one person besides the victim present, then that person feels 100% of the responsibility for acting. If there are 10 people present, then the responsibility is diffused throughout the group, an each person feels only 10% of the responsibility. Feeling 10% percent of of the responsibility might very well not be enough to motivate the person to act.

18.2.4 Stanford Prison Study

Philip Zimbardo’s famous Stanford Prison Experiment divided volunteer subjects randomly into two groups, prisoners and guards. Prisoners were picked up at their homes, charged, cuffed, and put into police cars, then taken to a station where they were informed of their rights, booked, finger printed, blindfolded, and placed in a holding cell. The “prison” was constructed in the basement of the psychology building at Stanford University. Guards were given no training, and were free to do whatever they thought was necessary to maintain order. The guards began to increasingly harass and humiliate the prisoners, forcing them to do things like clean out toilet bowls with their bare hands. Some guards were strict, but fair, others lenient, but some were hostile and creative in devising ways to humiliate the prisoners.

The experiment was planned for two weeks, but ended after six days for two reasons. First, the guards began escalating their abuse in the middle of the night when they thought no experimenters were watching, Second, a person brought in from outside to interview the guards and prisoners was outraged at what she saw. Given her response, it became clear that they needed to end the experiment15.

18.2.5 Asch Conformity Study

The autokinetic effect is common perceptual illusion — if you are in a dark room in which you can see only a small, stationary point of light, the light will appear to move. In the 1930’s, Muzafer Sheri, a pioneer of social psychology, found that people in a group who experience this effect develop a group norm; that is, after a time, they begin to see the point of light moving the same direction and the same distance. Interestingly, as people in the group are replaced, the new members will adopt the same group norm. This is true, even after several generations of new members. (Sherif 1935)

Sherif’s results were provocative, but they did have a problem, as Solomon Asch later pointed. Since the point of light is actually stationary, there isn’t a correct answer to how far it is moving. If there is not correct answer, then how is it possible to be sure that the subjects are conforming? So, Asch devised an experiment in which it would be clear if subjects were conforming.

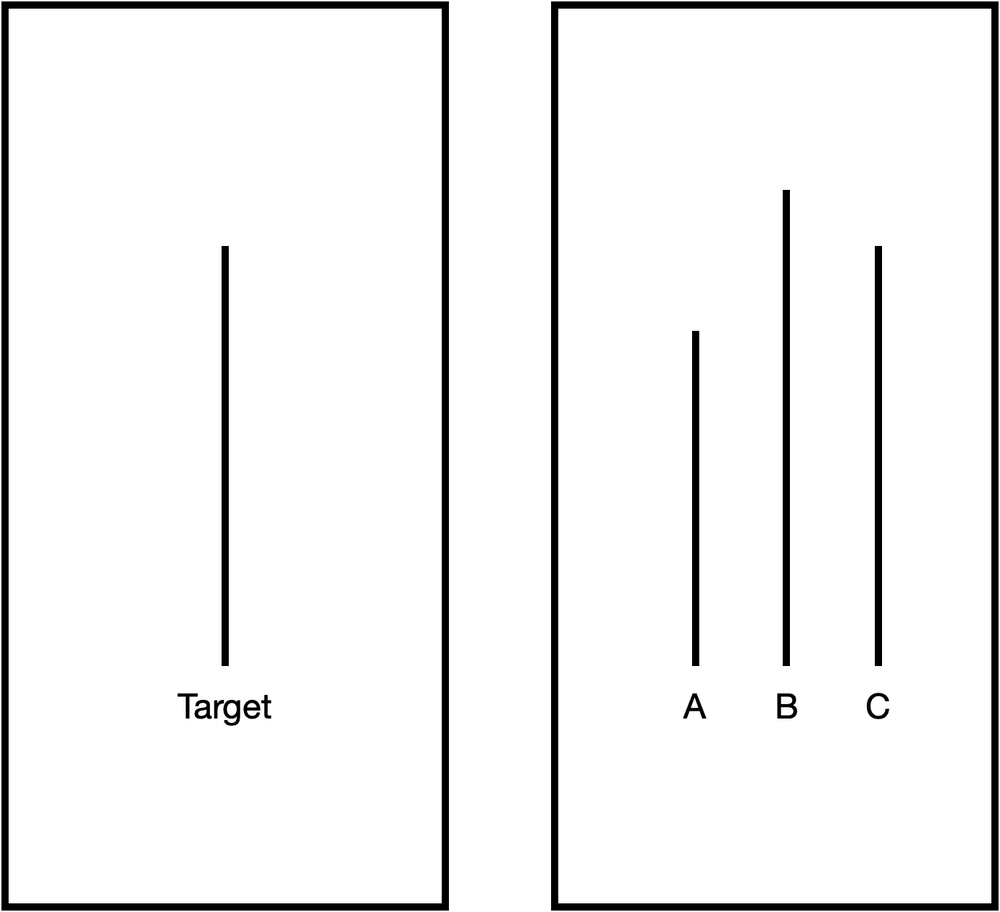

Students from Swarthmore College were chosen to participate in the study, and informed that it was a vision test. Each subject was placed in a room with seven other people. who were really confederates (people working with the experimenter.) The people were shown figures like this:

Figure 18.1: Asch Conformity Study

Each person was to state aloud which line (A, B, or C) was closest in size to the target line — the answer was intended to be obvious. The test subject always sat at the end of the row and would answer last. The confederates would give a clearly incorrect answer, and about 75% of the test subjects conformed to that wrong opinion at least once. The times that the confederates gave the right answer, less than 1% of the subjects gave the wrong answer. Later, when asked why they gave the wrong answer, most subjects said that they didn’t believe the answer was correct, but went along with the group to avoid being ridiculed. (Asch 1951)

It is important to note that Asch discovered that if there was only one confederate then the test subject would not conform. Disagreeing with one person seems to be no problem, but disagreeing with an otherwise unanimous group is different. More important, even in the larger group, if even one of the confederates refused to conform to the others, then the test subject would also not conform.

18.2.6 Milgram Experiment

The final experiment we’ll discuss is a famous one by Stanley Milgram, published in 1963. (Milgram 1963) The subjects were 40 men, ages 20–50. Two people were brought in, one was the actual test subject, and the other was an accomplice. They were told that the experiment was to study the effects of punishment on learning. A drawing was held to determine who would be the teacher and who would be the learner. Since the drawing was rigged, the test subject was always the teacher. The accomplice was strapped into a chair with an electrode attached to his wrist.

The subject read a series of word pairs to the learner. He then read the first word of a pair, along with four other words. The learner was to signal which of the four had been paired with the first word by pressing one of four switches. The teacher was at an instrument panel consisting of 30 switches in a line. Each switch was labeled with a voltage ranging from 15 to 450 volts. Groups of four switches were labeled with these designations:

- Slight Shock

- Moderate Shock

- Strong Shock

- Very Strong Shock

- Intense Shock

- Extreme Intensity Shock

- Danger: Severe Shock.

The last two groups were simply labeled “XXX”

With each successive wrong answer by the learner, the teacher was to increase the level of the shock, by announcing the new voltage level, and throwing the switch. The learners would give three wrong answer to one correct answer, and upon reaching 300 volts, pound on the wall. The subject would usually then turn to the experimenter for direction, who would tell the subject to wait 5–10 seconds for an answer, then keep increasing the shock level until the learner responded. If the subject wanted to quit, the experimenter would say these lines, beginning with the first and going on as necessary:

- Please continue. or Please go on.

- The experiment requires that you con- tinue.

- It is absolutely essential that you con- tinue.

- You have no other choice, you must go on.

It was predicted that only a small minority of the subjects would continue to 450 volts, and that almost all would go no further than 240 volts, which was labeled “Very Strong Shock.” The actual results were that no one quit before 300 volts, and 26 continued all of the way to 450 volts.

18.3 Actor-Observer Difference

We have seen many ways in which experiments have shown that features of the situation prompt our behavior. Those external causes are more powerful than we usually think. People do tend to give external explanations in two different cases: first, for their own bad actions, and second, for others’ good actions. On the other hand, they tend to give internal explanations for their own good actions and for others’ bad ones. This is called the “Actor-observer difference.”

It is important to note that the Fundamental Attribution Error does not mean that people are not responsible for their actions. Even though the situation inclines us to act wrongly, that doesn’t mean that we have to do so. We must ask ourselves if everyone in this situation do the same thing? If the answer is no, then the external reason, although true, does not excuse.