Chapter 3 Academic Writing

3.1 Language

Use a formal style of writing within your thesis. There are many useful pages on the web for searching for synonyms, such as thesaurus. Do not use short forms and avoid excessive usage of active language in first person (I (we) start with, I (we) did this, I (we) found that, I (we) conclude that). Do not refer to the reader and author as we (We need to understand […], after we have delved into […]). Avoid judgmental statements and informal language (So…, like…).

Be precise in your formulations and wording. When starting to elaborate on a specific aspect, do not use indeterminate names or object descriptions. Instead, be precise to allow the reader to follow your line of argumentation. When framing that Utilizing Financial Data faces challenges […] ensure that you either explain what the term challenges means in the following sentence or replace the term with a more precise description, e.g. Utilizing Financial Data faces the challenges of data extraction and preprocessing. Same holds for the reference to other sources. Refrain from stating Other sources suggest […], but more explicitly state the sources Other sources, such as Riordan (2019) and Hendershott (2020), suggest […]. Limit your usage of determinate articles (this, these). This requires the reader to look back into your text (or at least think back) which causes an interruption of the forward flow of the text. Ideally, each sentence does make sense on its own, without the surrounding context. Do not use rhetorical questions. Delete is if possible from the text to avoid nominalization. Ensure that when using pronouns the reference is clear and cannot be mistaken. Capitalization should be consistent.

If you want to enumerate a set of arguments, incooperate the enumeration your your text. You can either use numerical or alphabetical enumeration labels to introduce each point or emphasize the different points verbally (First, second, third).

Example:This is an enumeration with a (1) first point that determines a statement and a (2) second point that does so as well.

Alternatively, we can also introduce that, first, we can make point and, second, we can also make another point.

Acronyms can be used, but might decrease readability of your text. When using acronyms introduce them the first time you make use of the full word and use the abbreviations afterwards. Keep the utilization of the abbreviation consistent. When describing a theory or concept stick to one exact wording to guide the reader through the text. Do not change wording to avoid repetition and create variation.

Use varying sentence lengths and structures to enhance the flow of your text and avoid monotonicity. Noticing that sentences are typically constructed of subject, verb and object, you can easily generate flow in your text by varying the extensiveness of each sentence component. Overabundand sentences with too many information or nested constructions exhaust the reader. Parallel ideas should be expressed in parallel ways.

Example:Our low-complexity algorithm facilitates its investment decision by computing and comparing […]. Our high-complexity algorithm facilitates its investment decision as machine learning technique by […].

3.2 Tables and Figure

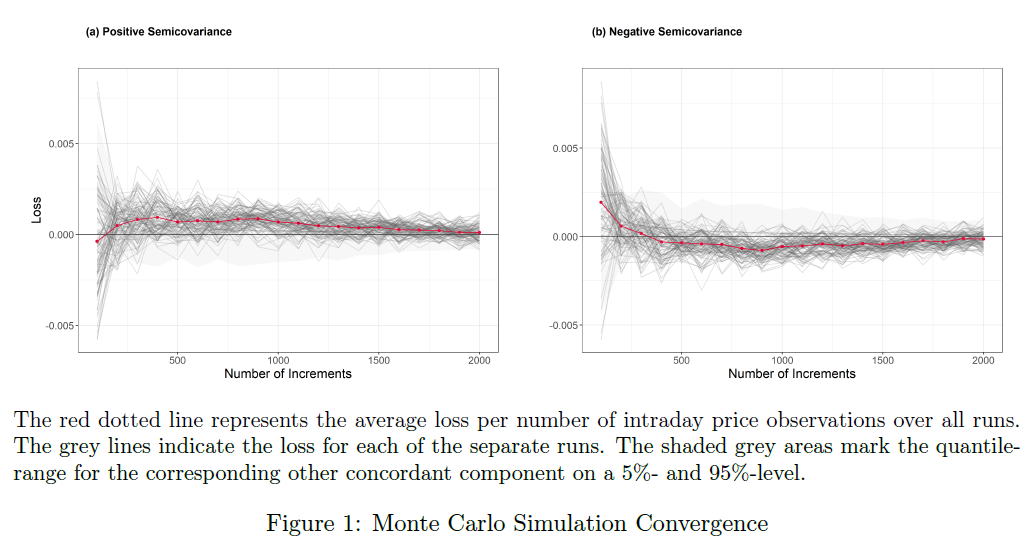

Each table and figure needs to have a number and a title. You might additionally add a remark to the table/figure to provide more in-depth information about displayed measures, aggregation techniques or information of the table or figure. Make sure your table/figure has a short, concise and informative name. Do not include detailed information in the table’s/figure’s title, you should use the remark for adding information to the object instead of the title.

Example:

When including a table or figure within the report, ensure you are referring to the table/figure explicitly within your text. Make sure tables and figures have a corresponding title and numbering. When using a multitude of tables and figures you should create a list of tables/figures.

Each table and figure should be actively referred to in the main text. If you are not referring to the table/figure do not include it in the main text.

Example:The obtained probabilities are in line with the graphic results in Figure 1 and indicate a number […]

Be selective about the incorporation of tables/figures in your thesis and do not overload on them. You can put a table/figure into the appendix if its contents are not vital for understanding and visualizing a section’s content, but do support your line of argumentation.

Do not report too detailed information within your table/figure. Ensure you round reported numbers to the same number of decimal digits as in the table. Think about how detailed your reader needs the information to be in order to understand the message you are trying to convey. Use meaningful names for lines, points and areas in your figures.

3.2.1 Footnotes

We do not recommend the use of footnotes, however if explanatory notes still prove necessary to your document but disrupt the actual flow of the text, you can provide supplemental information in footnotes. When providing footnotes, be brief and focus on only one subject. Recall that a footnote should only be a subordinate. As footnotes break the flow of reading they should ideally be positioned at the end of the sentence or even the end of a paragraph. Try to limit your comments to a single small paragraph. You can also point readers to information that is available in more detail in other literature sources.

3.3 Equations

Ensure that you explain all variables used within your equation. A single variable should be for one specific item and cannot have multiple meanings.

If you are not using inline equations (i.e., equations within the text), make sure that you number the equations chronologically. Also, it is important to write your variables in mathmode instead of plain text: \(y\) instead of y.

Example:

\(\begin{equation} B_{t} - B_{s} \sim N(0,t-s), \end{equation}\)

\(\begin{equation}(1) \end{equation}\)

with \(B_0\) denoting an arbitrary starting value of the series and the Gaussian increments \(B_{t1} - B_{t0}, B_{t2} - B_{t1},..., B_{tT} - B_{tT-1}\) with \(0 = t0 < t1 <...< tT\) being independent.

Equations that comprise multiple lines should be aligned.

Example:\(\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} &\mathbf{\widehat{P}}_t = \sum_{i = 1}^{M} p(\mathbf{r}_{t-i\Delta}) p(\mathbf{r}_{t-i\Delta})^T \\ &\mathbf{\widehat{N}}_t = \sum_{i = 1}^{M} n(\mathbf{r}_{t-i\Delta}) n(\mathbf{r}_{t-i\Delta})^T \end{aligned} \end{equation}\)

\(\begin{equation}(2) \end{equation}\)

\(\begin{equation} \mathbf{\widehat{M}}_t = \sum_{i = 1}^{M} \left( p(\mathbf{r}_{t-i\Delta}) n(\mathbf{r}_{t-i\Delta})^T + n(\mathbf{r}_{t-i\Delta}) p(\mathbf{r}_{t-i\Delta})^T \right). \end{equation}\)

\(\begin{equation}(3) \end{equation}\)