Topic 1 History of the Key Ideas in Chemistry

To talk about the history of Chemistry, one must need to know the present state of Chemistry. What key ideas are there in modern Chemistry?

But more importantly, how did these ideas get developed over the years?

These ideas are:

- There are about 100 elements in our world.

- Elements are made up of atoms. Atoms are made up of protons, neutrons, and electrons.

- The arrangement of electrons in an atom affects its periodicity.

- Chemical bonds form when atoms share electrons.

- Molecules change via chemical reactions.

- Atom arrangements determines properties.

1.1 Key Ideas of Modern-Day Chemistry

1.1.1 Elements

Figure 1.1: The Periodic Table of Elements

Figure 1.1 shows the famous periodic table of elements.

Figure 1.2: Elemental Composition of the Human Body and the Universe

While not all elements have the same abundance, all matter is made up of elements or combinations of them (e.g., compounds):

Figure 1.3: Some Examples of Compounds

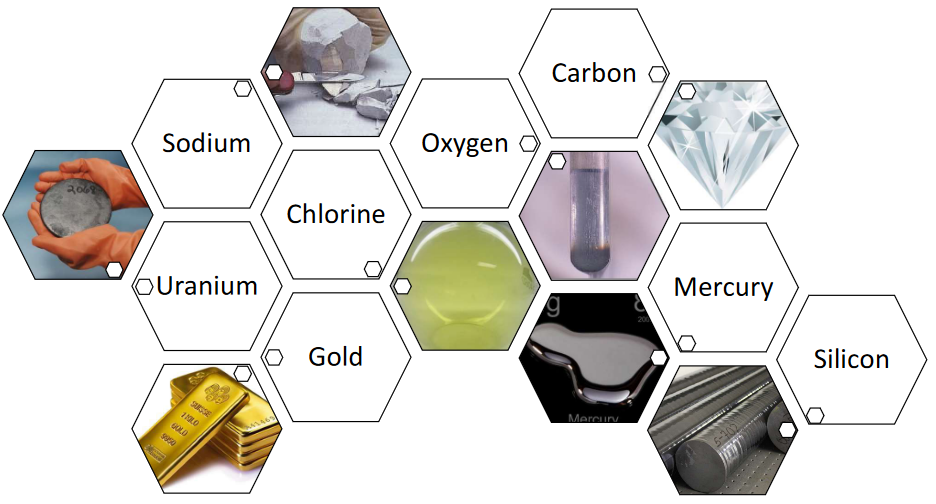

Furthermore, many elements appear very different to the human eye:

Figure 1.4: Elements of All Sorts

For instance, hydrogen (i.e., H2) is a gas, iron is a solid metal, mercury is a liquid metal, and diamond (an allotrope of carbon) is a crystal.

1.1.2 Atoms

Only during 1981 could scientists actually “see” atoms. How was it that scientists during the 19th century were able to figure out their existence?

Figure 1.5: Software Depiction of Atoms

All electrons in atoms are placed in “orbitals”: from their nucleus to their outside valence electrons (i.e., 1s 2s 2p 3s 3p 4s 3d…). Electrons on the outer orbital determines the chemical properties of the element (i.e., their periodicity).

Nevertheless, many of the elements in figure 1.4 appear different, but are actually very similar. All of those elements are composed of atoms: the basic unit of elements.

Figure 1.6: Structure and Arrangement of Carbon Atoms in a Diamond

For instance, 197 grams of gold contains \(6.02 \times 10^{23}\) gold atoms. 12 grams of diamond (carbon) atoms also contain \(6.02 \times 10^{23}\) atoms 1.

1.1.3 Chemical bonds and molecules

The world is generally made up of matter that is made up of atoms and strongly linked to one another via “chemical bonds”.

Figure 1.7: Water Molecules

Like already mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, how the atoms in a molecule arrange themselves determines the size and the properties of the molecule.

Figure 1.8: Carbon Allotropes and DNA

1.1.4 Chemical reactions

When compounds change, so do the arrangment of their atoms (i.e., bonds are broken and re-formed):

Figure 1.9: Combustion of Methane Gas

When methane gas reacts with O2 molecules, a combustion reaction happens to yield carbon dioxide, water, and heat (i.e., the fire that one sees).

1.1.5 Essential physics theories

Thermodynamics is the conservation of energy: its second law states that the universe is always getting more disordered (i.e., entropy always increases).

Quantum mechanics, on the contrary, deals with the wave nature of particles. One might have seen the famous Schrodinger equation before:

\[\begin{equation} H(t) | \psi(t) \ge ih\frac{\partial}{\partial t} \text{|}\psi(t)\text{>} \end{equation}\]

1.2 World History

The history of Chemistry (and science in general) cannot be separated from world history. This section aims to provide a very brief (and selective) overview of world history to make some sense of the context of the course’s content.

Figure 1.10: Ancient Egypt During 3150 BC to 300 BC

Alchemy started in Egypt in 3150 BC.

Figure 1.11: Ancient China During 2100 BC to 400 BC

During 2100 BC to 400 BC was the birth of Chinese civilization - the rise of Chinese alchemy occurred during 400 BC.

Figure 1.12: Ancient Greece During 500 BC to 250 BC

During 500 BC to 250 BC, the philosophers Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato arose. At around 300 BC, Alexander the Great was born.

Figure 1.13: Rise of Roman Empire During 500 AD

The Roman empire rose around 500 AD.

Figure 1.14: European Dark Ages and the Silk Road

During 500 - 1400, Europe lapsed into the dark ages: a period of time that resulted in intellectual hibernation. Europe was able to escape the dark ages via Islamic civilization.

At the same time, the silk road facilitated the exchange of knowledge; the rise of Islamic cities (e.g., Baghdad, Damascus, Cordoba, and Alexandria) in the 6th century took over Greek-Roman knowledge and expanded on it.

In ancient China, the Tang, Song, and the Mongol empires also invented gunpowder in the 10th century.

Figure 1.15: The World After the 15th Century

After the 15th century, the age of reason, the age of enlightenment, and the industrial revolution all happened - the history of Chemistry then mainly concentrated around the West (mainly in Europe, but also in parts of the Americas in later periods too).

1.3 Makeup of the World Through Ancient Eyes

With only five senses and no laboratory equipment, what did ancient civilizations conclude about the world?

The natural philosopher aims to explain the world (i.e., its makeup and its natural phenomena) without using supernatural causes as justifications.

However, the latter is sometimes part of a wider system that incorporates spirituality; some theories are vague and suggestive.

Yet, there are many common themes between ancient Indian, ancient Chinese, and ancient Greek societies: atomic theory, the four (or five) element model, monism, and so on.

1.3.1 Ancient Greeks

Figure 1.16: Geography of Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece geographically includes today’s Greece, the Western coast of Turkey, and South Italy.

Figure 1.17: Aspects of Ancient Greece

Figure 1.17 displays some notable places and people from ancient Greece.

1.3.1.1 Phusikoi

The earliest Greek natural philosophers sought natural explanations for natural phenomena instead of attributing all phenomena to the supernatural.

Phusikoi - the Aristotle term for the pre-Socratic natural philosopher - eventually evolved into the word “Physics”.

1.3.1.1.1 Thales of Miletus

Figure 1.18: Thales of Miletus

Monism claims that the universe is made up of one substance: the arche (i.e., the principle or the origin).

Thales chose water as his arche. Since water can change into multiple different states - ice (i.e., solid), water (i.e., liquid), and steam (i.e., gas) - it seemed like a sensible choice at the time.

1.3.1.1.2 Anaximander

He chose apeiron (i.e., boundless or infinite) as his arche. Apeiron is an indeterminate substance, made “out of which things came and to which they returned”.

1.3.1.1.3 Anaximenes of Miletus

He chose air as his arche

“Being made finer it becomes fire, being made thicker it becomes wind, then cloud, then (when thickened still more) water, then earth, then stone: [a]nd the rest come into being from these. He, too, makes motion eternal, and says that change, also comes about through it.”

Simplicius’ Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics (6th cent. CE)

1.3.1.2 Atoms

This was an idea pioneered by Leucippus and Democritus, Abdera, and Thrace.

The word Atomos refers to indivisible and fundamental entities that are eternal and unchangeable (notwithstanding their motions). The ancient Greeks claims that atomos are infinite.

“Either the atoms rebound from one another, or if the colliding atoms are hooked or barbed, or their shapes otherwise correspond to one another, they cohere and thus form compound bodies. Change of all sorts is accordingly interpreted in terms of the combination and separation of atoms. The compounds thus formed possess various sensible qualities, such as colour, taste, temperature and so on, but the atoms themselves remain unaltered in substance.”

Simplicius quoting from Aristotle commenting on Democritus

Furthermore, atomos comes in all shapes. New materials are produced by the agglomeration of atoms; all materials change as agglomerations break and form.

1.3.1.3 Four Elements

Figure 1.19: Empedocles of Agrigentum

Empedocles - a Greek born in Agrigentum (a Greek city in Sicily) - postulated that all matter is formed from four elements: fire, water, air, and earth. Different ratios of the four elements yielded different materials.

Two motive powers: philotes (i.e., love) and neikos (i.e., strife) unites or divides the elements to yield different materials respectively.

Empedocles also showed that air was an actual substance: he observed trapped air bubbling out of water.

1.3.1.4 Aristotle

Figure 1.20: Bust of Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and the teacher of Alexander the Great. He is an iconic Greek philosopher with contributions to metaphysics, natural philosophy, ethics, logic, political science, and many other fields.

He was also responsible for introducing primary matter (i.e., hule):

Figure 1.21: Aristotle’s Four-Element Model

This model is an adaptation of Empedocles’ four element model, albeit combined with four other elemental qualities: hotness, coldness, dryness, and wetness.

“…hot with dry and moist with hot, and again cold with dry and cold with moist. And these four couples have attached themselves to the apparently”simple" bodies (Fire, Air, Water, and Earth) in a manner consonant with theory. For Fire is hot and dry, whereas Air is hot and moist (Air being a sort of aqueous vapour); and Water is cold and moist, while Earth is cold and dry…"

Book II, Chapter 3 De Generatione et Corruptione

1.3.1.4.1 Aristotle’s cosmos

Figure 1.22: Aristotle’s Cosmos

Aristotle divided up the universe into two regions: the celestial region (i.e., spheres containing the moon, the sun, and the planets) and the terrestrial region (i.e., the region within the lunar sphere).

Within the terrestrial region, the four elements are in a flux and are changeable. Hence, if all motions were to cease, the four elements would be separated into four layered spheres (from lightest to heaviest). However, the aforementioned does not happen as the elements are constantly in motion and (dis)associating with other elements to give the many materials that we know.

A fifth element - the aether - fills the celestial region. The aether is permanent and doesn’t change; planets and stars are made of this element.

This model dominated Western (and later Arabic) thoughts until the renaissance in the 1500s (when modern science chipped away this understanding).

1.3.2 Ancient India

Hindu religion and much of Indian culture traced back to the Vedas (from religious canon from the Vedic age [1500 - 500 BCE]).

Figure 1.23: Ancient Indian Scripture

The vedas: a large body of religious texts that originate in ancient India are made up of the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda, and the Atharvaveda.

1.3.2.1 Five elements

The Upanishads claimed that all (in)animate matter are derived from five elements (i.e., Bhuta):

- Space (akasa) \(\rightarrow\) sound (sabda)

- Air (vayu) \(\rightarrow\) touch (sparsa)

- Fire (agni) \(\rightarrow\) color (rupa)

- Water (ap) \(\rightarrow\) taste (rasa)

- Earth (prthivi) \(\rightarrow\) odor (gandha)

The Upanishad also has much room for interpretation:

- Darshanas (six schools of Indian philosophies): they provide a complete package of epistemology, ethics, soteriology, and metaphysics to interpret the Upanishad and the Vedas.

- Other “non-orthodox” philosophical systems (e.g., Buddhism and Jainism)

Some of these philosophical schools also describe some form of atomic theory: for instance, Jainism, Buddhism, and Samkhya-Yoga

1.3.2.2 Atomic theory

The Nyāya-Vaiśesika school concerns logic and natural philosophy. He has the most developed ideas on natural philosophy among philosophical schools.

Figure 1.24: Kanada Kashyapa

Kanada Kashyapa - an Indian philosopher - was thought to have developed the concept of the atom.

According to him, there are three infinite and pervasive entities:

- Time

- Space

- (akasa) Aether \(\rightarrow\) the continuous substrate that sound is carried.

There are also four different kinds of atoms:

- Air (vayu) \(\rightarrow\) touch (sparsa)

- Fire (agni) \(\rightarrow\) touch, color (rupa)

- Water (ap) \(\rightarrow\) touch, color, taste (rasa)

- Earth (prthivi) \(\rightarrow\) touch, color, taste, odor (gandha)

Kanada argued that if matter can be divided indefinitely, then one cannot account for the size between “a mountain and a mustard seed” as there is an infinite amount of particles in both objects. Conversely, if there are ultimate indivisible parties, then the differences in size will yield a different number of ultimate particles.

Kanada also argues that atoms are eternal and not perceived. Hence, we can only infer its effects.

Furthermore…

- The smallest thing we can sense are motes, or dust specks.

- Two primary atoms of the same kind yield a binary system. These binary systems then form a triad that is big enough to be observed.

- The triads then give rise to the many materials in our universe (including lifeforms).

1.3.3 Ancient Chinese

Figure 1.25: Ancient Chinese Geography

墨子 (or Mozi) was a philosopher who lived during the Warring States era. He was famous for his ethical and political philosophy that opposed Confucianism.

Figure 1.26: Mojing Scripture

墨经 (see above figure) are scriptures that contains thoughts on natural philosophy.

The 端 (i.e., Duan) refers to cutting material to zero thickness until one arrives at the basic materials. The duan has no separation in between.

Anything that cannot be cut further into half is the “atom”.

1.3.3.1 Counter arguments

“一尺之棰,日取其半,万世不竭”

Gongsun Long

The above quote block roughly translates to:

“A foot long stick, if you cut it by half everyday, you will never ever get to the time when you can stop (cutting it into yet another half)”.

Gongsun Long

Ancient Chinese texts are very concise and hence, are difficult to interpret.

1.3.3.2 Five elements

The《洪范》(i.e., hongfan) contains one of the earliest statements regarding the five elements.

These elements are:

- Water (tends to go low and is salty)

- Fire (tends to go up and is bitter)

- Wood (can be straight or curvy and is sour)

- Metal (malleable and spicy)

- Earth (used to grow crops and is sweet)

According to the《国语》(Guoyu), the mixing of earth, metal, wood, water, and fire gives rise to all living things.

1.3.3.3 Monism and dualism

Ancient Chinese texts also suggest that different materials came about from a single entity.

Yin referred to females, negative, darkness, cold, and the moon. Yang referred to males, positive, light, heat, and the sun. Everything in the world can be described as a combination or an opposition of these two forces.

1.3.3.4 Five elements and dualism

The qi of the universe can be separated to yin and yang. Qi can then be differentiated into four seasons or into five elements: each giving rise to the other or countering one another.

These principles are widely used in Chinese alchemy.

Note that 1 mole = \(6.02 \times 10^{23}\) atoms↩︎