Cranes

Hwang Sunwŏn (1915-2000)

Translated by David R. McCann

(Story originally published in 1953)

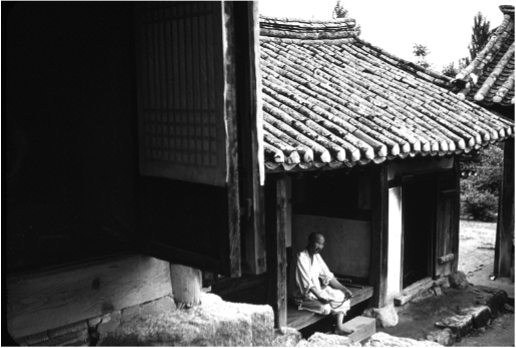

Beneath the high, clear autumn sky just north of the 38th boundary the village was quiet and alone.

In the empty houses, there might be just a white gourd on the dirt floor between rooms, leaning against another white gourd.

Old people met by chance would turn aside, pipes held behind their backs. And children, being children, turned away at some distance. Everyone’s face was marked by fear.

The area showed no signs of what might be called the broken remnants of the present conflict. But it somehow did not seem like the old village where he had grown up as a youngster.

In the chestnut grove on the back hill, Sŏngsam halted his steps. There he climbed one of the trees. It seemed as if he could hear from a distance the shouts of the old grandfather with the wen: “You little son-of-a-guns, climbing someone else’s tree again!”

The old grandfather with the wen had probably passed away in the time since. He hadn’t been among the old people encountered in the area so far.

Holding on to the chestnut tree, for a moment Sŏngsam looked up at the blue autumn sky. Even without the branch being shaken, one of the remaining chestnuts opened, and the nut slipped out, and fell.

As he reached the front of a house, the temporary headquarters for the Public Peace Corps, he saw there was some young fellow tied up in handcuff rope.

It didn’t seem to be anyone he had seen before in the village, so he went up close for a look at his face. He was stunned. Wasn’t it his closest childhood friend, Tŏkchae?

What was going on, he asked the Public Peace Corpsman who had come over from Ch’ŏnt’ae with him. Vice chairman of the Farmers Collective Committee, this one was, caught hiding out in his own house.

Sŏngsam squatted down there on the dirt floor, a lighted cigarette in his mouth.

Tŏkchae was going to be sent off to Ch’ŏngdan. One of the Public Peace Corps members was going to take him.

Lighting a new cigarette from the one he had just finished, Sŏngsam stood up again.

“I’ll take this sunnavabitch.”

Tŏkchae all this time kept his face turned away and did not even try to look in Sŏngsam’s direction.

The two came out of the village.

Sŏngsam smoked one cigarette after another. The cigarettes seemed to have no flavor. He just kept drawing the smoke in deep, and letting it out. After a while, the thought came to him that this Tŏkchae fellow, he might want a cigarette too. He remembered when they were young, how they would make cigarettes out of pumpkin leaves and smoke them behind the wall, so the grown-ups wouldn’t know. But how could he offer a cigarette to a guy like this one, today?

Once, when they were young, he had gone with Tŏkchae to swipe chestnuts from the old grandfather with the wen. It had been Sŏngsam’s turn to climb the tree. Next instant, the old grandfather was shouting at them. He slipped and fell out of the tree. The chestnut burs pierced his backside, but they just ran. Only when they had gone far enough so the old grandfather with the wen couldn’t follow, did he turn his backside to Tŏkchae. It hurt like anything, pulling out the chestnut burs. He couldn’t help the tears that trickled down. Tŏkchae suddenly reached out with a fistful of his own chestnuts and stuck them in Sŏngsam’s pocket. . . .

Sŏngsam threw away the cigarette he had just lit. He makes up his mind not to light another while escorting this fellow Tŏkchae.

They reached the hill road. The hill is where he and Tŏkchae had gone all the time to cut fodder, until two years before Liberation when Sŏngsam moved to a place near Ch’ŏnt’ae, south of the 38th.

Sŏngsam, overwhelmed by sudden anger, gave a shout.

“You son of a ! How many people have you killed so far?”

Only then does Tŏkchae look over, then lower his head again. “Sunnavabitch ! How many people have you killed?”

Tŏkchae raises his head and turns his way. He shoots a look at Sŏngsam. His expression turns darker, and the edges of his mouth, surrounded by his dangling beard, quiver and shake.

“So, that’s how you killed people?”

Sunnavabitch! Somehow Sŏngsam’s heart feels relieved at its core. As if something blocking it has eased and fallen loose. But,

“Some guy gets to be vice chairman of the Farmers Collective Committee, why didn’t you run off? Hiding out with some secret mission?”

Tŏkchae says nothing.

“Go ahead, tell the truth! What sort of mission was it you were hiding out to do?”

But Tŏkchae just keeps walking silently along. Clear enough, this one is feeling caught. It’s good to see their faces at a moment like this, but he keeps his face turned away, and doesn’t look over.

Grasping the pistol that he carried at his waist, Sŏngsam says, “It’s no use trying to defend yourself. You’re going to be shot, no doubt about it. So you might as well tell the truth right here and now.”

Without turning his head, Tŏkchae replies,

“There’s nothing to defend myself about. I’m just the son of a dirt-poor farmer. I’m known as a guy who can handle the hard work, and that’s why I was made vice chairman of the Farmers Cooperative Committee. If that’s a crime to get killed for, there’s nothing to be done about it. All I’m good at, all I ever was good at to stay alive, is digging in the dirt.”

He pauses for a moment.

“My father is laid up now. It’s half a year already.”

Tŏkchae’s father was a widower, a poor farmer getting old, caring just for his son Tŏkchae. Seven years ago his back had already given out and his face was covered with age spots.

“You married?” A moment, and “Yeah, married.” “Who with?” “Short Stuff.”

No. Short Stuff? This is great. Short Stuff. Kind of fat, and too short to know the skies were high, just how wide the earth is. Sort of a loner. They hadn’t liked that, so he and Tŏkchae, together they used to tease her all the time and make her cry. And now Tŏkchae had gone and married Short Stuff.

“So, any kids?”

“The first is coming this fall.”

At this, Sŏngsam could hardly keep himself from laughing.

He was the one who had asked with his own mouth if there were any kids, but when he heard that the first was coming this fall it was almost more than he could bear. Even not pregnant, Short Stuff ’s little body had a tummy almost too big to reach around. But realizing this was not the time to laugh or make jokes about such a thing, he says,

“But don’t you think it’s suspicious, you hanging around, not trying to get away?”

"I thought of trying to get away. They said when they came up from the south this time, all the men, all of them would be caught and killed, so all the males between seventeen and forty, they were made to go north. I thought of getting away too, even if I had to carry my father on my back. But he said no, he couldn’t. Where would a farmer go, and leave the farming? And besides, my father, he grew old doing the farming, trusting in me; I wanted to be the one to close his eyes with my own hands. People like us, all we know is working the earth to stay alive. What good would it do us to run away?

Last June, it was Sŏngsam who had fled. He had told his father secretly at night that he was going to flee. Sŏngsam’s father had said the same thing then. If farm workers left the farming, where would they go? So Sŏngsam had fled alone. As he wandered the strange streets and hamlets of the south, always in his head was the farm work he had left to his old parents and young family. But fortunately, they were all as healthy now as they had been then.

They crossed the ridge of the hill. Now it was Sŏngsam who walked along with his face turned away. The autumn sun was hot on his forehead. He thought, a day like this, the weather was perfect for threshing.

As they came down from the hill, Sŏngsam gradually slowed down and halted his steps.

Over in the center of the fields, looking like some people wearing their white clothes, backs bent, surely that was a flock of cranes. The place that had become the demilitarized zone along the 38th parallel. Even though people had stopped living there, it was still a place where the cranes continued to live as before.

Once when Tŏkchae and Sŏngsam were about twelve, without the grown-ups knowing, the two of them had set a trap and caught a crane. It was a Tanjŏng crane. They had tied it up, even its wings, and every day the two of them would come and stroke its neck, ride on its back, making a fuss over it. Then one day, they heard the grown-ups in the area whispering about something. Someone had come from Seoul to shoot a crane. He even had some permit from the government-general for collecting specimens. The two had run off down the road. It did not matter that the grown-ups might find out and give them a scolding. All they could think was that their crane must not die. Without stopping to catch their breath, they crawled through the weeds to untie the lasso around the crane’s legs and loose the rope from its wings. But the crane could hardly walk. Probably from being tied up for so long. Holding it together, the two of them heaved the crane up into the sky. Suddenly there was a shot. The crane flapped its wings two, three, four times, then sank down again. Had it been shot? But at the next instant, as another Tanjŏng crane spread its wings wide in the bushes right beside them, their own crane, the one that had come down to earth, stretched out its long neck, gave a cry, and flying up into the sky, sweeping in a circle over the heads of the two boys, vanished into the distance. For a long time the two boys could not take their eyes away from the blue sky into which their crane had vanished . . . “Hey, time for us to go crane hunting,” Sŏngsam suddenly announced.

Tŏkchae was stunned, not knowing what was going on.

“I’ll make a snare with the rope here. You chase a crane over.”

Sŏngsam had untied the rope and was crawling away into the weeds.

The color drained from Tŏkchae’s face. The words flashed through his mind from just before, “You’re going to be shot.” Soon a bullet would come from where Sŏngsam had gone crawling off.

Sŏngsam turned his head back toward him.

“Hey, what are you waiting for? Chase a crane or something over here!”

At last Tŏkchae understood, and began crawling through the weeds.

Just then, two or three cranes, their huge wings spread, went soaring through the clear autumn sky.