MMWR reports selected for review

The 56 full reports selected for this review are listed here in chronological order of publication, with links from the report identifier (e.g., mm6802a1) to the text of the report below, from "HTML" and "PDF1" to the HTML and PDF versions on the MMWR website, respectively, and from "PDF2" to a local copy of the PDF version, followed by citation information.

-

Report mm6802a1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2019-01-18;68(2):25-30.

García et al. Opioid prescribing rates in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties among primary care providers using an electronic health record system — United States, 2014–2017. -

Report mm6806a2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2019-02-15;68(6):135-139.

Doyle et al. Interim estimates of 2018–19 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness — United States, February 2019. -

Report mm6817a3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2019-05-03;68(17):388-395.

Kariisa et al. Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential — United States, 2003–2017. -

Report mm6827a2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2019-07-12;68(27):604-607.

Su et al. Workplace secondhand tobacco smoke exposure among U.S. nonsmoking workers, 2015. -

Report mm6834a3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2019-08-30;68(34):745-748.

Beauregard et al. Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among U.S. infants born in 2015. -

Report mm6841e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2019-10-18;68(41):919-927.

Siegel et al. Update: Interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury — United States, October 2019. -

Report mm6844a1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2019-11-08;68(44):993-998.

O’Neil et al. Lung cancer incidence in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties — United States, 2007–2016. -

Report mm6848a1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2019-12-06;68(48):1105-1111.

Patel et al. Progress toward regional measles elimination — worldwide, 2000–2018. -

Report mm6903a1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-01-24;69(3):57-62.

Peterson et al. Suicide rates by industry and occupation — National Violent Death Reporting System, 32 states, 2016. -

Report mm6906a3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-02-14;69(6):161-165.

Divers et al. Trends in incidence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths — selected counties and Indian reservations, United States, 2002–2015. -

Report mm6911a5 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-03-20;69(11):298-302.

Schieber et al. Variation in Adult outpatient opioid prescription dispensing by age and sex — United States, 2008–2018. -

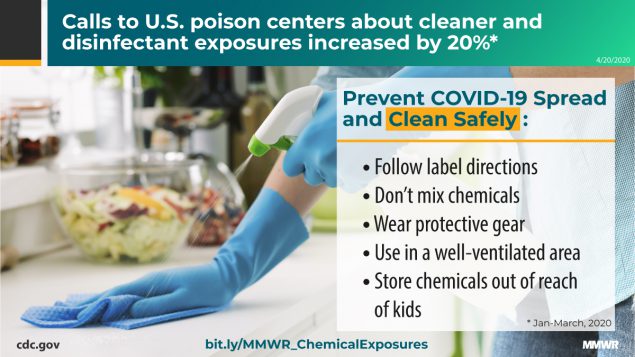

Report mm6916e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-04-24;69(16):496-498.

Chang et al. Cleaning and disinfectant chemical exposures and temporal associations with COVID-19 — National Poison Data System, United States, January 1, 2020–March 31, 2020. -

Report mm6920e2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-05-22;69(20):632-635.

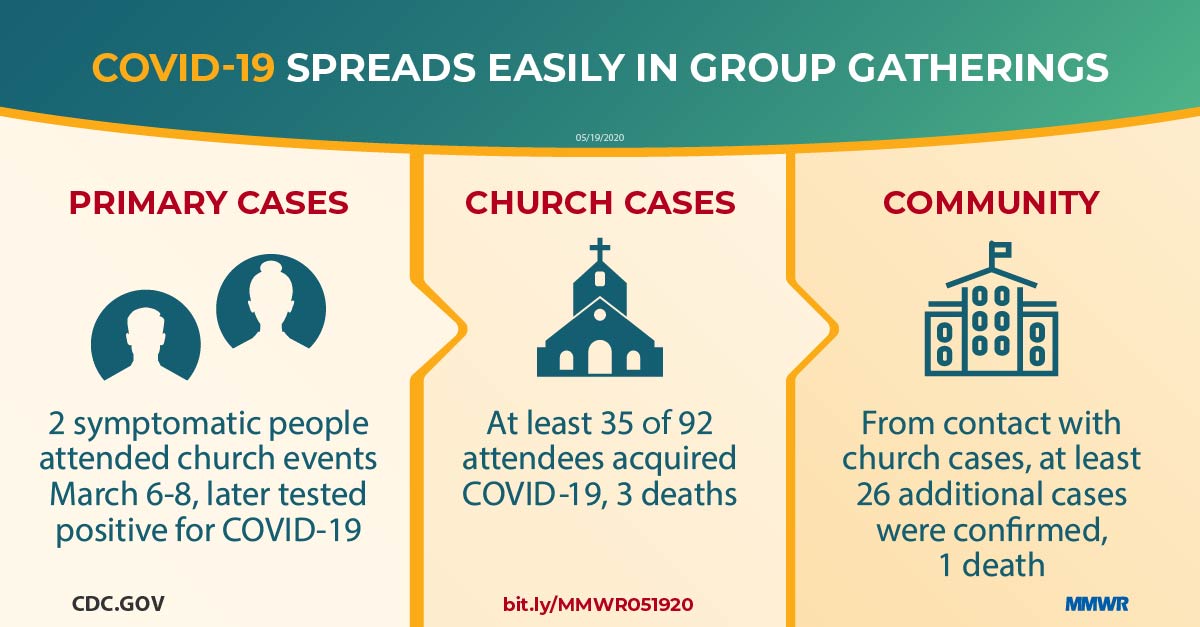

James et al. High COVID-19 attack rate among attendees at events at a church — Arkansas, March 2020. -

Report mm6923e4 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-06-12;69(23):714-721.

Payne et al. SARS-CoV-2 infections and serologic responses from a sample of U.S. Navy service members — USS Theodore Roosevelt, April 2020. -

Report mm6924e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-06-19;69(24):751-758.

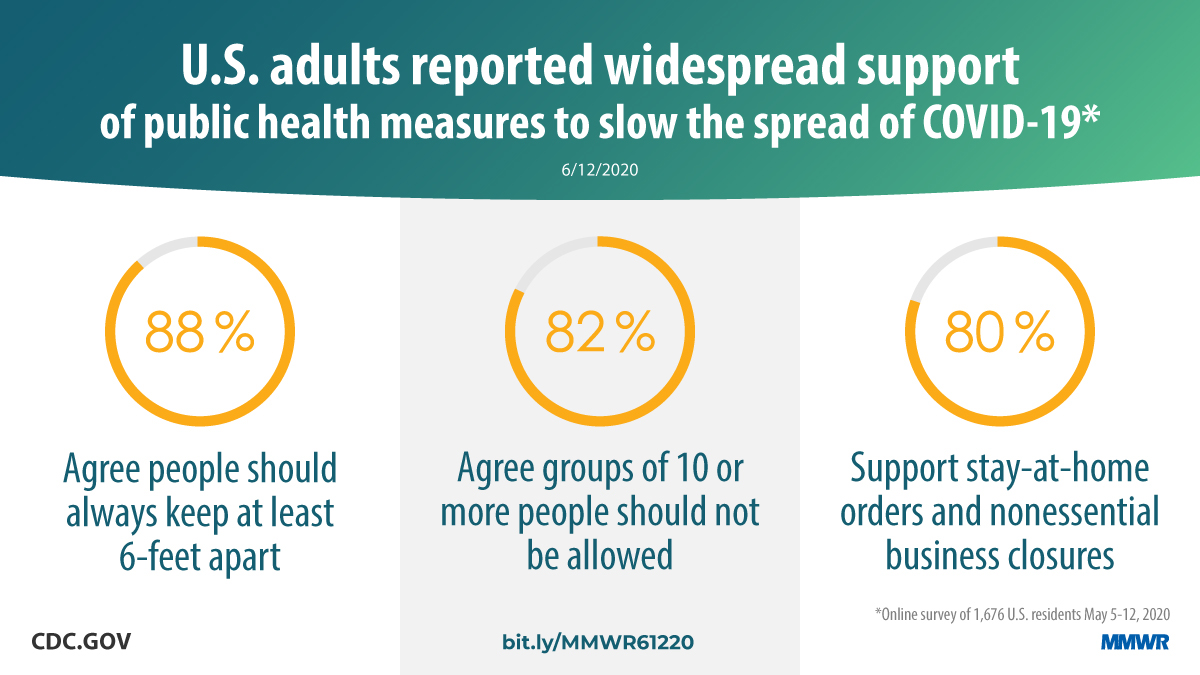

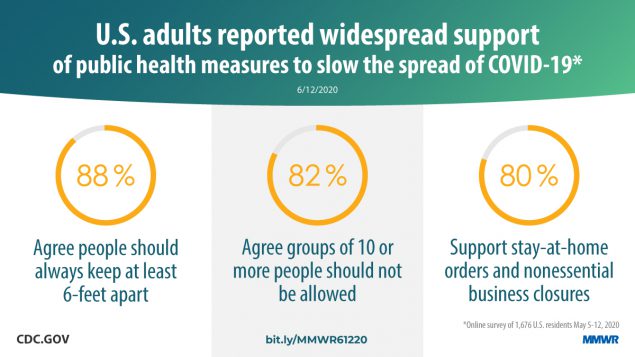

Czeisler, Tynan, et al. Public attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs related to COVID-19, stay-at-home orders, nonessential business closures, and public health guidance — United States, New York City, and Los Angeles, May 5–12, 2020. -

Report mm6925a1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-06-26;69(25):769-775.

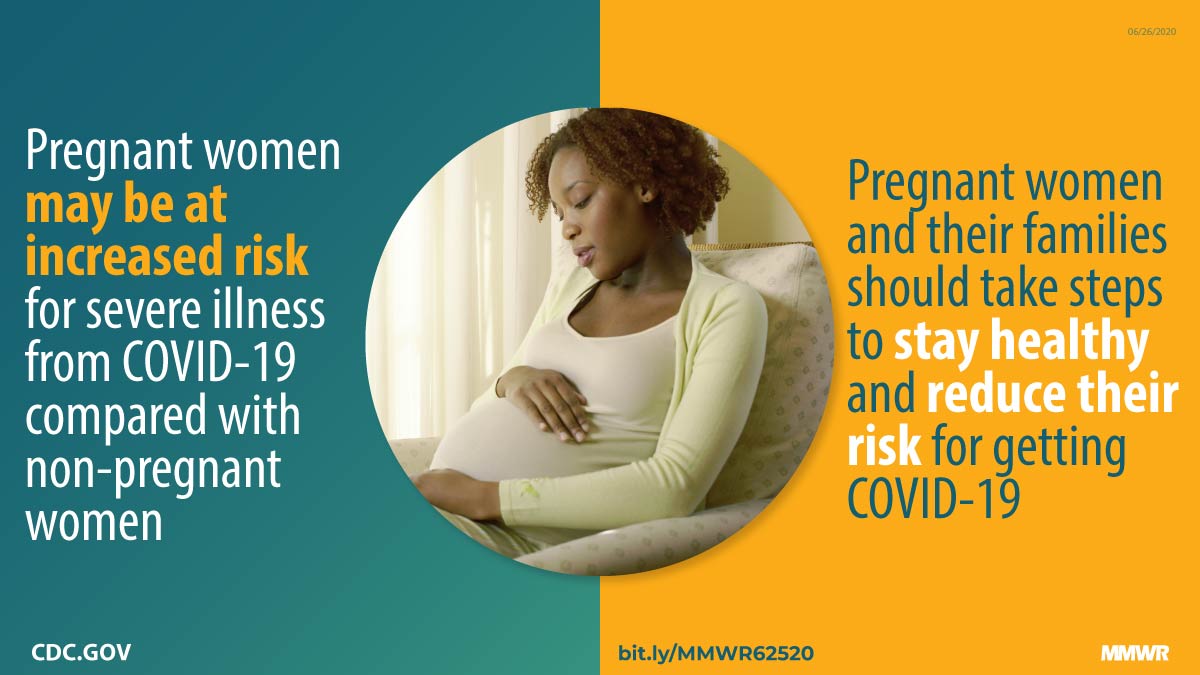

Ellington et al. Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status — United States, January 22–June 7, 2020. -

Report mm6927a4 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-07-10;69(27):870-874.

Waltzman et al. Trends in emergency department visits for contact sports–related traumatic brain injuries among children — United States, 2001–2018. -

Report mm6928e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-07-17;69(28):933-937.

Fisher, Barile, et al. Factors associated with cloth face covering use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, April and May 2020. -

Report mm6930e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-07-31;69(30):993-998.

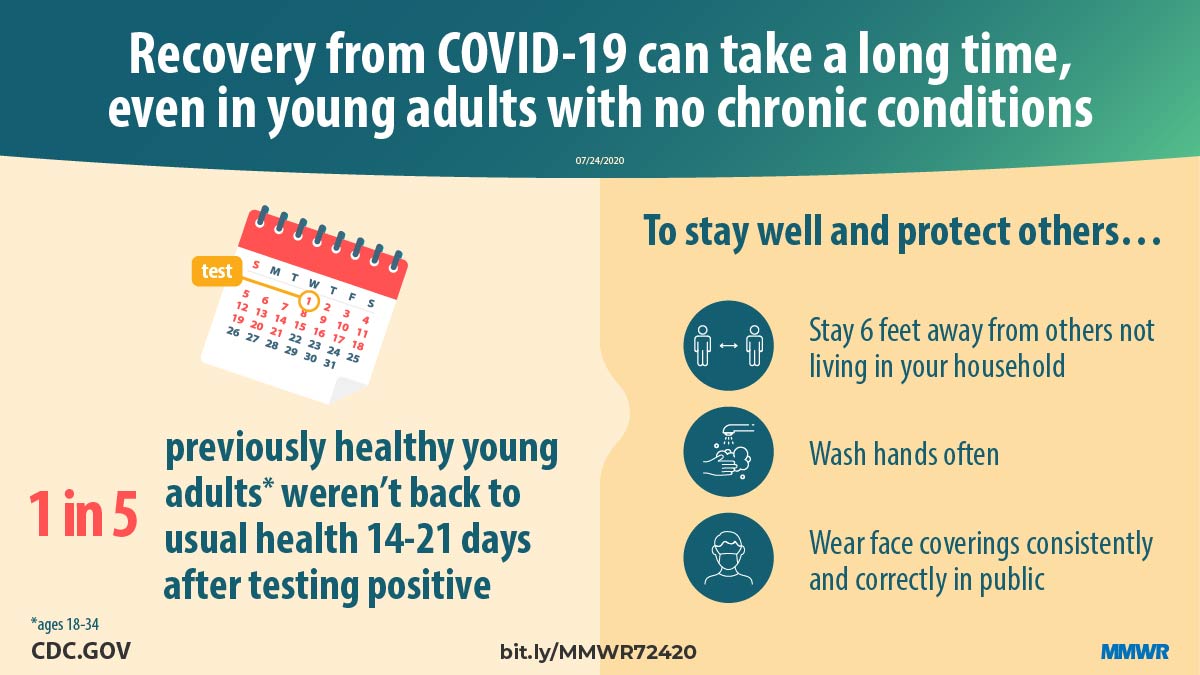

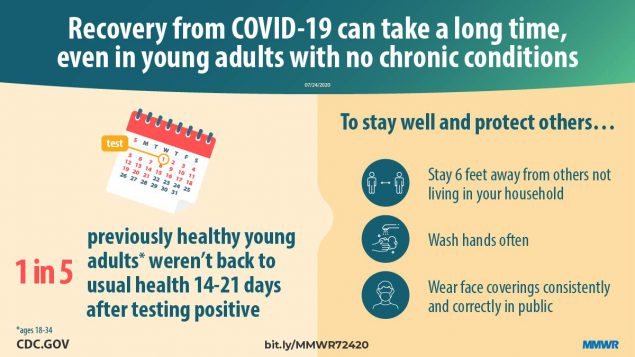

Tenforde et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network — United States, March–June 2020. -

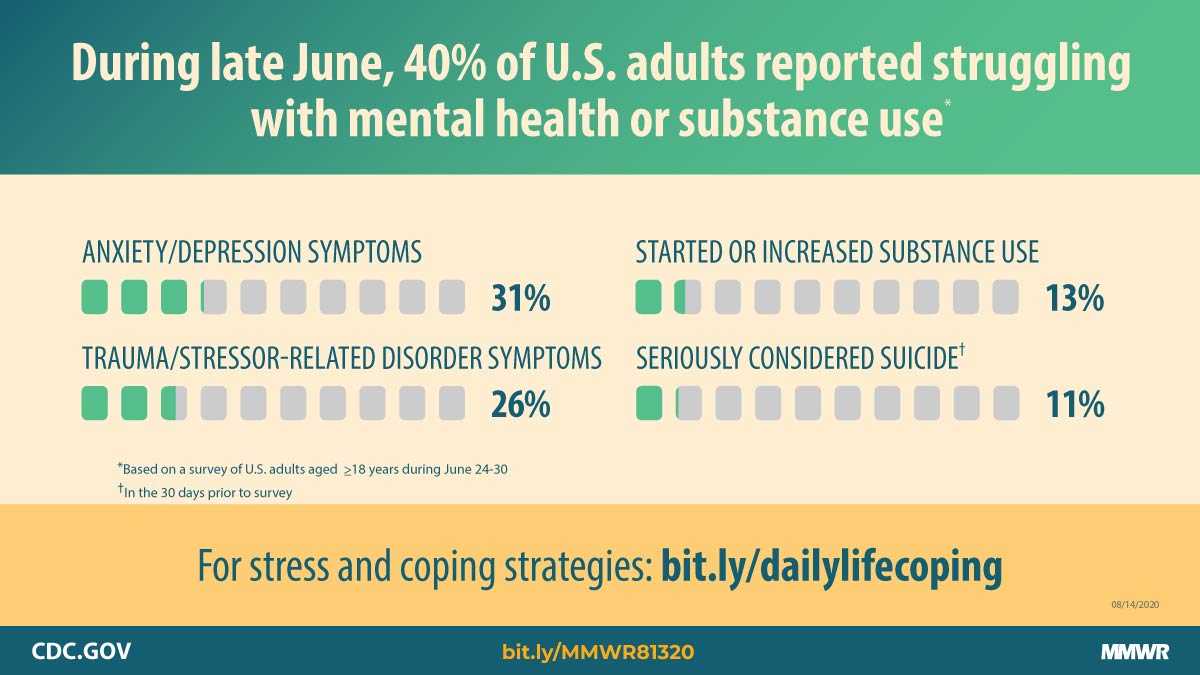

Report mm6932a1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-08-14;69(32):1049-1057.

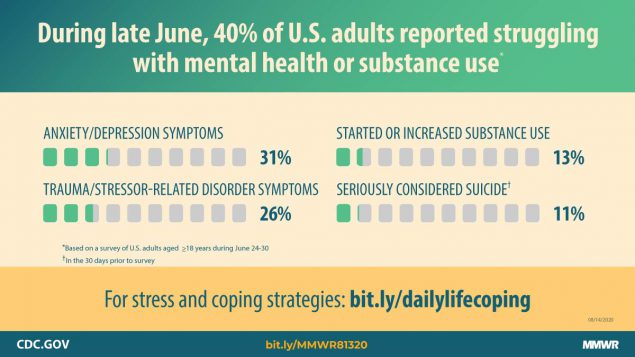

Czeisler, Lane, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. -

Report mm6932e5 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-08-14;69(32):1095-1099.

Hatfield et al. Facility-wide testing for SARS-CoV-2 in nursing homes — seven U.S. jurisdictions, March–June 2020. -

Report mm6935a2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-09-04;69(35):1198-1203.

Moreland et al. Timing of state and territorial COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and changes in population movement — United States, March 1–May 31, 2020. -

Report mm6935e2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-09-04;69(35):1221-1226.

Self et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among frontline health care personnel in a multistate hospital network — 13 academic medical centers, April–June 2020. -

Report mm6936a5 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-09-11;69(36):1258-1264.

Fisher, Tenforde, et al. Community and close contact exposures associated with COVID-19 among symptomatic adults ≥18 years in 11 outpatient health care facilities — United States, July 2020. -

Report mm6939e2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-10-02;69(39):1410-1415.

Leeb et al. COVID-19 trends among school-aged children — United States, March 1–September 19, 2020. -

Report mm6943e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-10-30;69(43):1576-1583.

Kambhampati et al. COVID-19–associated hospitalizations among health care personnel — COVID-NET, 13 states, March 1–May 31, 2020. -

Report mm6944e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-11-06;69(44):1641-1647.

Zambrano et al. Update: Characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status — United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. -

Report mm6947e2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-11-27;69(47):1777-1781.

Van Dyke et al. Trends in county-level COVID-19 incidence in counties with and without a mask mandate — Kansas, June 1–August 23, 2020. -

Report mm6949a2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2020-12-11;69(49):1848-1852.

Gilbert et al. Racial and ethnic differences in parental attitudes and concerns about school reopening during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, July 2020. -

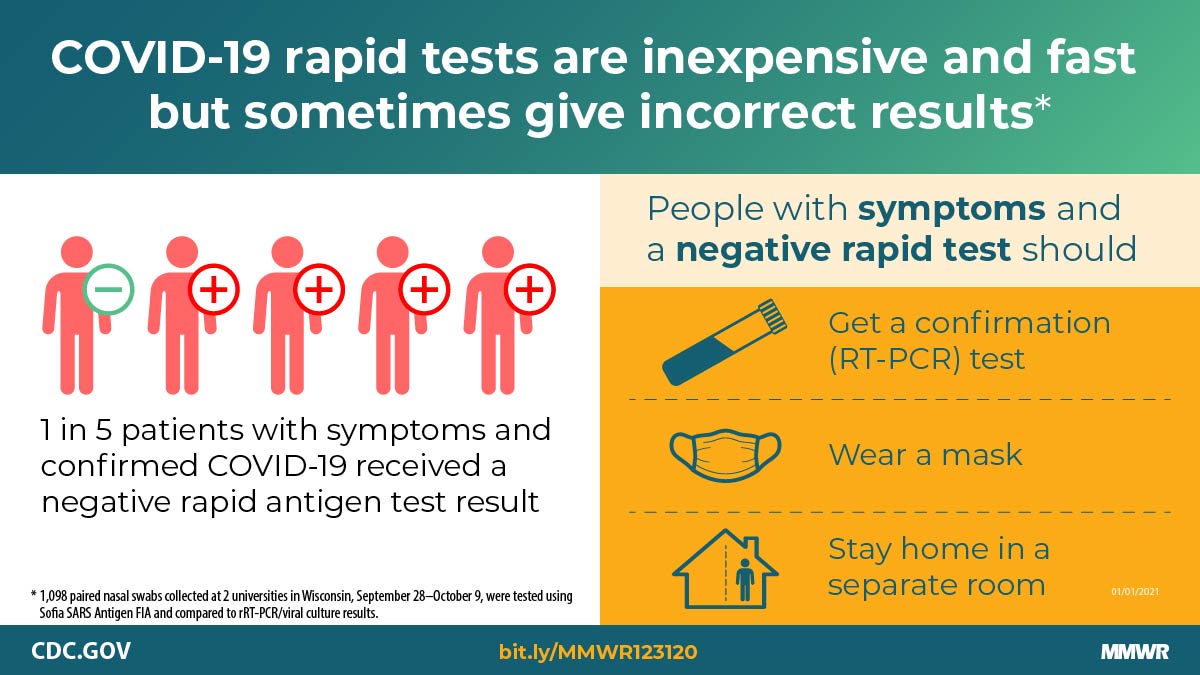

Report mm695152a3 (HTML PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-01-01;69(5152):1942-1947.

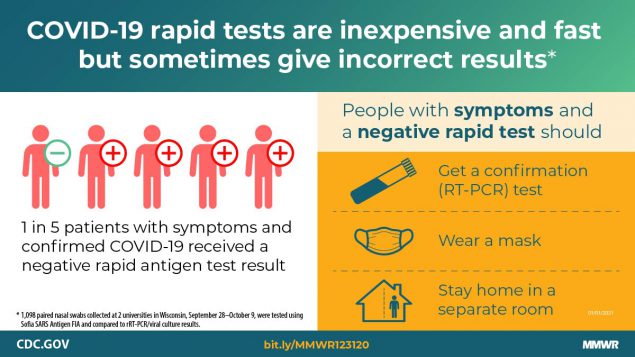

Pray et al. Performance of an antigen-based test for asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 testing at two university campuses — Wisconsin, September–October 2020. -

Report mm7001a4 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-01-08;70(1):14-19.

Leidner et al. Opening of large institutions of higher education and county-level COVID-19 incidence — United States, July 6–September 17, 2020. -

Report mm7004e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-01-29;70(4):136-140.

Falk et al. COVID-19 cases and transmission in 17 K–12 schools — Wood County, Wisconsin, August 31–November 29, 2020. -

Report mm7006e2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-02-12;70(6):212-216.

Joo et al. Decline in COVID-19 hospitalization growth rates associated with statewide mask mandates — 10 states, March–October 2020. -

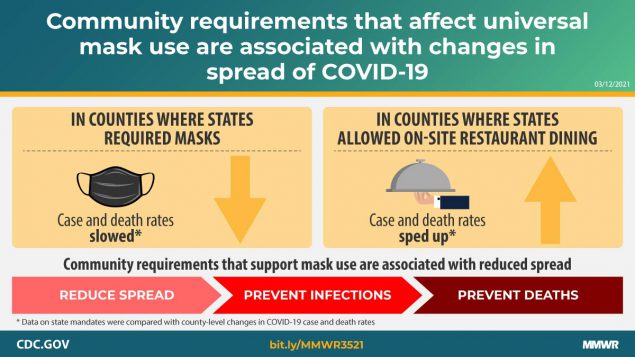

Report mm7010e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-03-12;70(10):350-354.

Guy et al. Association of state-issued mask mandates and allowing on-premises restaurant dining with county-level COVID-19 case and death growth rates — United States, March 1–December 31, 2020. -

Report mm7010e4 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-03-12;70(10):355-361.

Kompaniyets et al. Body mass index and risk for COVID-19–related hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, and death — United States, March–December 2020. -

Report mm7011e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-03-19;70(11):396-401.

Britton et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine among residents of two skilled nursing facilities experiencing COVID-19 outbreaks — Connecticut, December 2020–February 2021. -

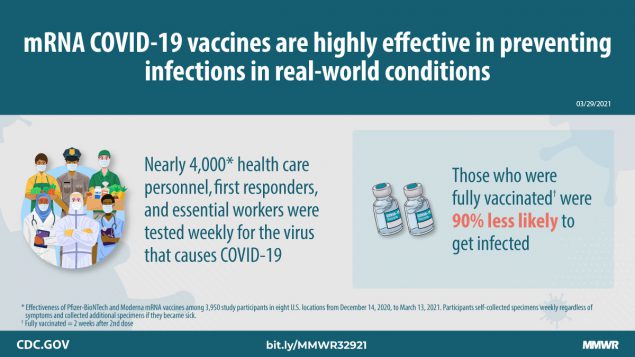

Report mm7013e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-04-02;70(13):495-500.

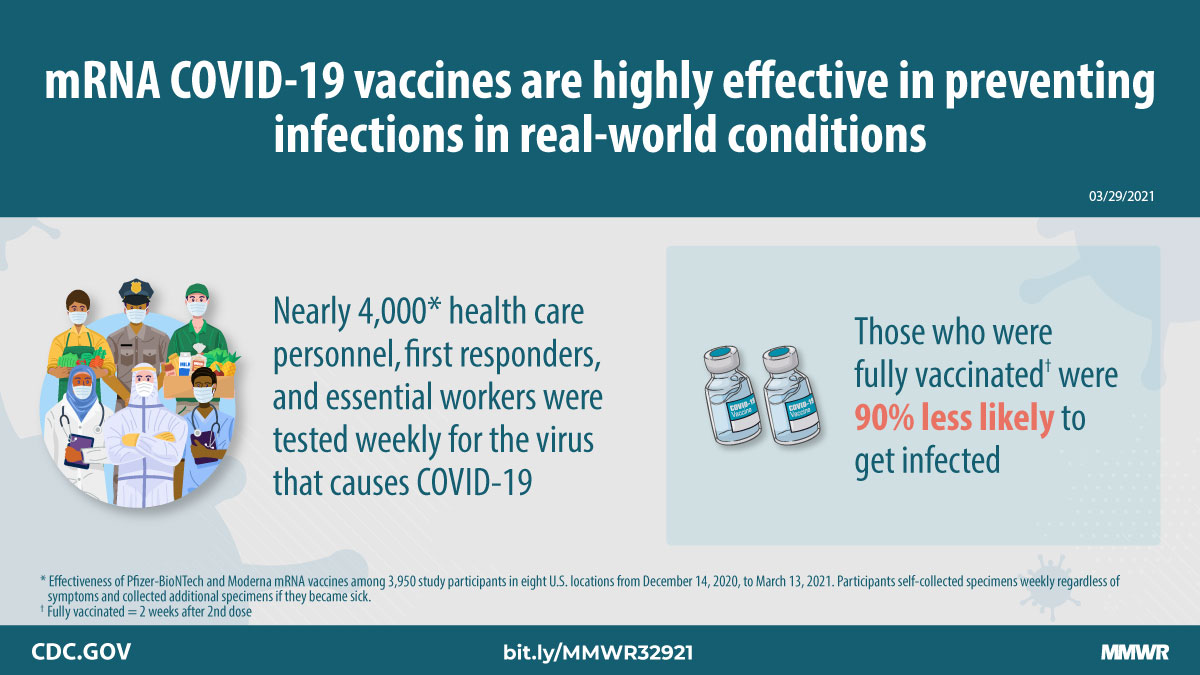

Thompson et al. Interim estimates of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among health care personnel, first responders, and other essential and frontline workers — eight U.S. locations, December 2020–March. -

Report mm7018e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-05-07;70(18):674-679.

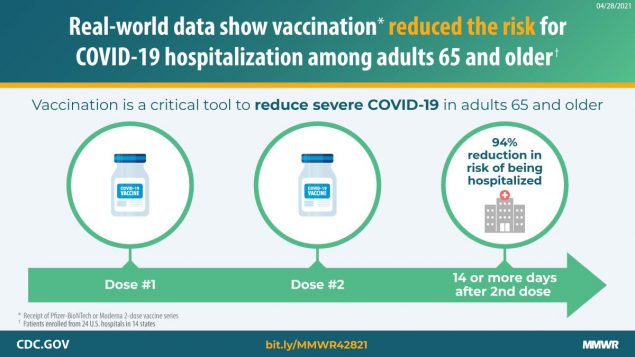

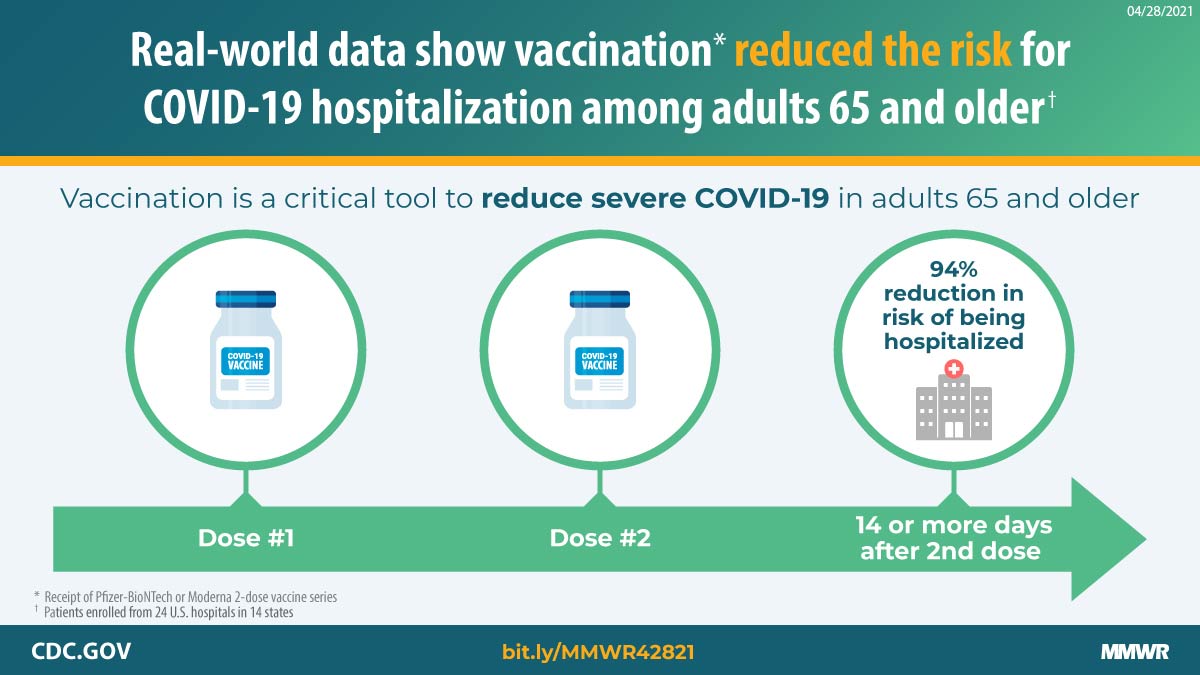

Tenforde et al. Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines against COVID-19 among hospitalized adults aged ≥65 years — United States, January–March 2021. -

Report mm7021e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-05-28;70(21):779-784.

Gettings et al. Mask use and ventilation improvements to reduce COVID-19 incidence in elementary schools — Georgia, November 16–December 11, 2020. -

Report mm7023e2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-06-11;70(23):858-864.

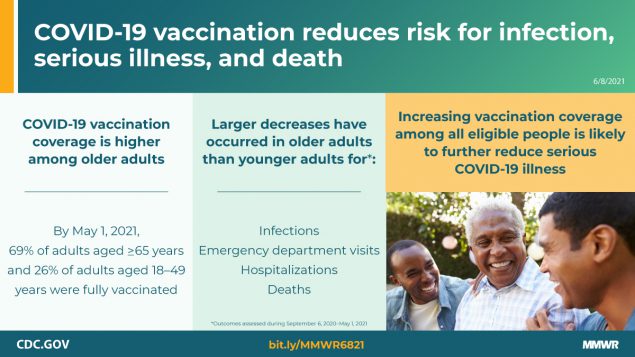

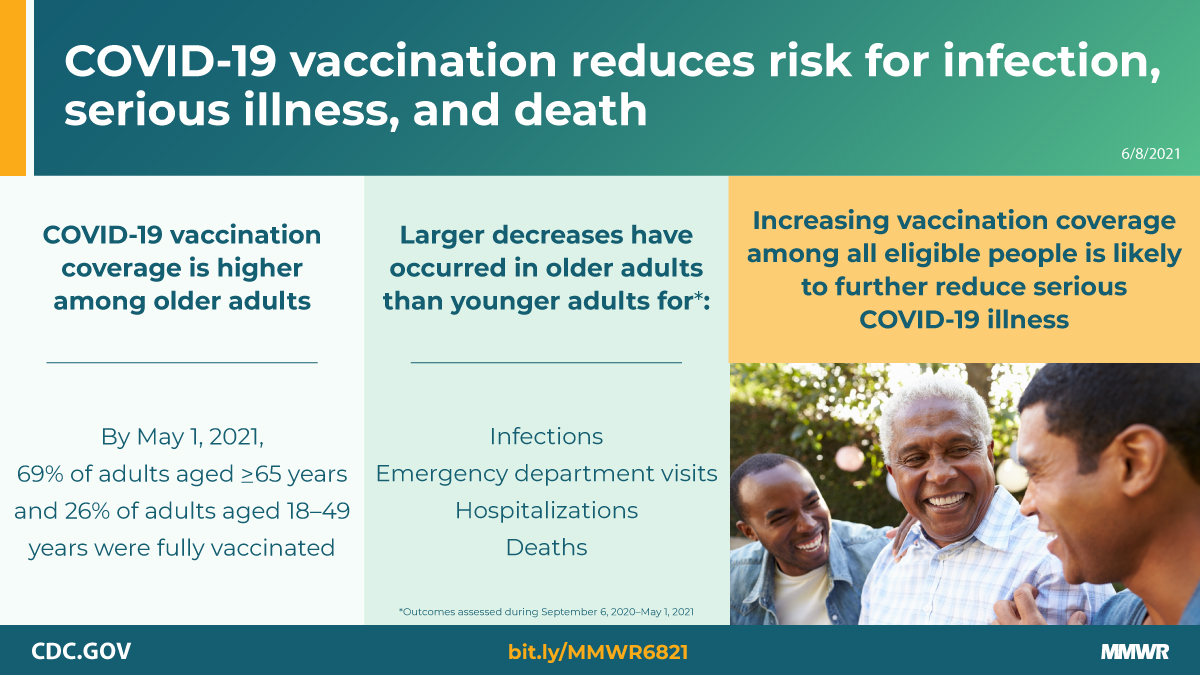

Christie et al. Decreases in COVID-19 cases, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and deaths among older adults following the introduction of COVID-19 vaccine — United States, September 6, 2020–May 1, 2021. -

Report mm7024e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-06-18;70(24):888-894.

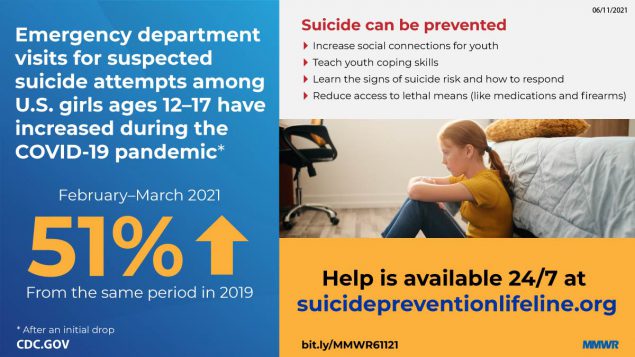

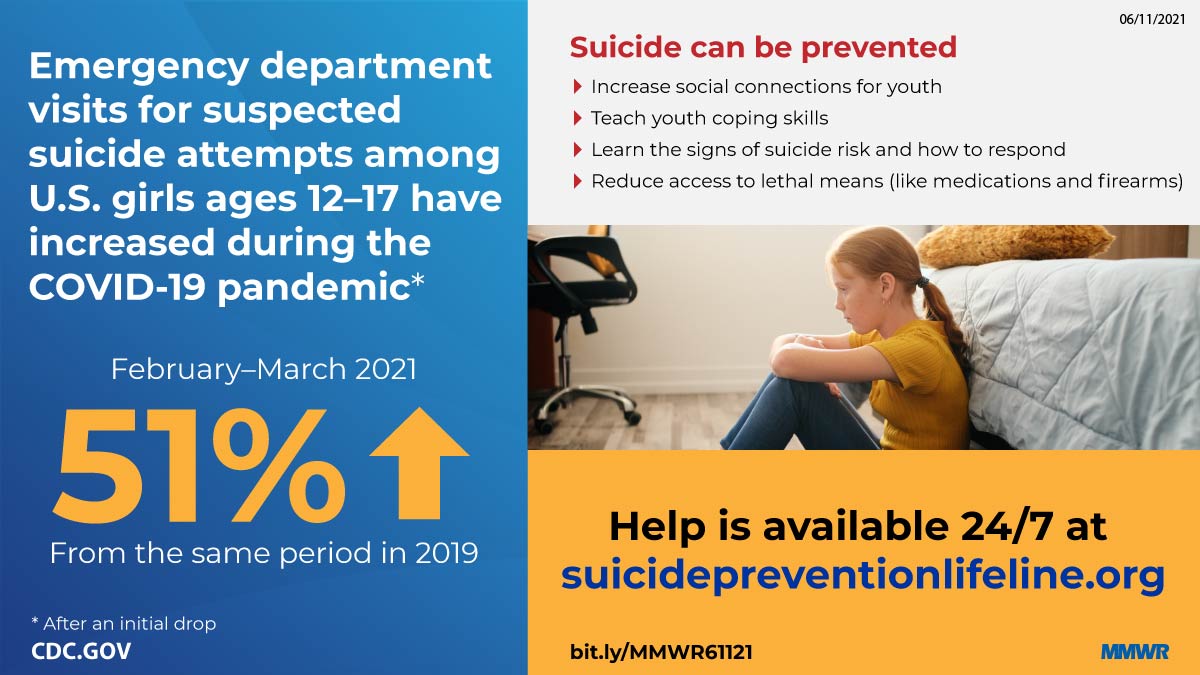

Yard et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. -

Report mm7031e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-08-06;70(31):1053-1058.

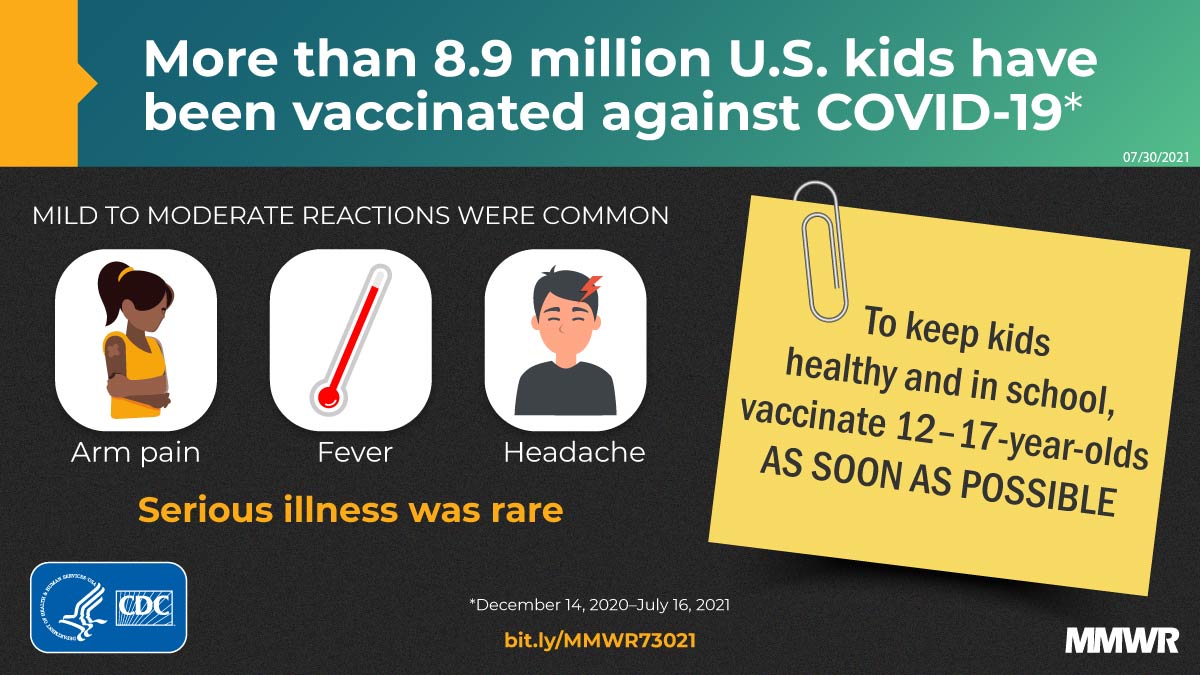

Hause et al. COVID-19 vaccine safety in adolescents aged 12–17 years — United States, December 14, 2020–July 16, 2021. -

Report mm7032e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-08-13;70(32):1088-1093.

Moline et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing hospitalization among adults aged ≥65 years — COVID-NET, 13 states, February–April 2021. -

Report mm7034e5 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-08-27;70(34):1170-1176.

Griffin et al. SARS-CoV-2 infections and hospitalizations among persons aged ≥16 years, by vaccination status — Los Angeles County, California, May 1–July 25, 2021. -

Report mm7037e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-09-17;70(37):1284-1290.

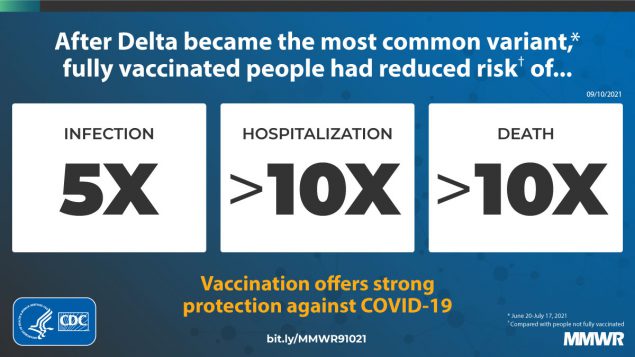

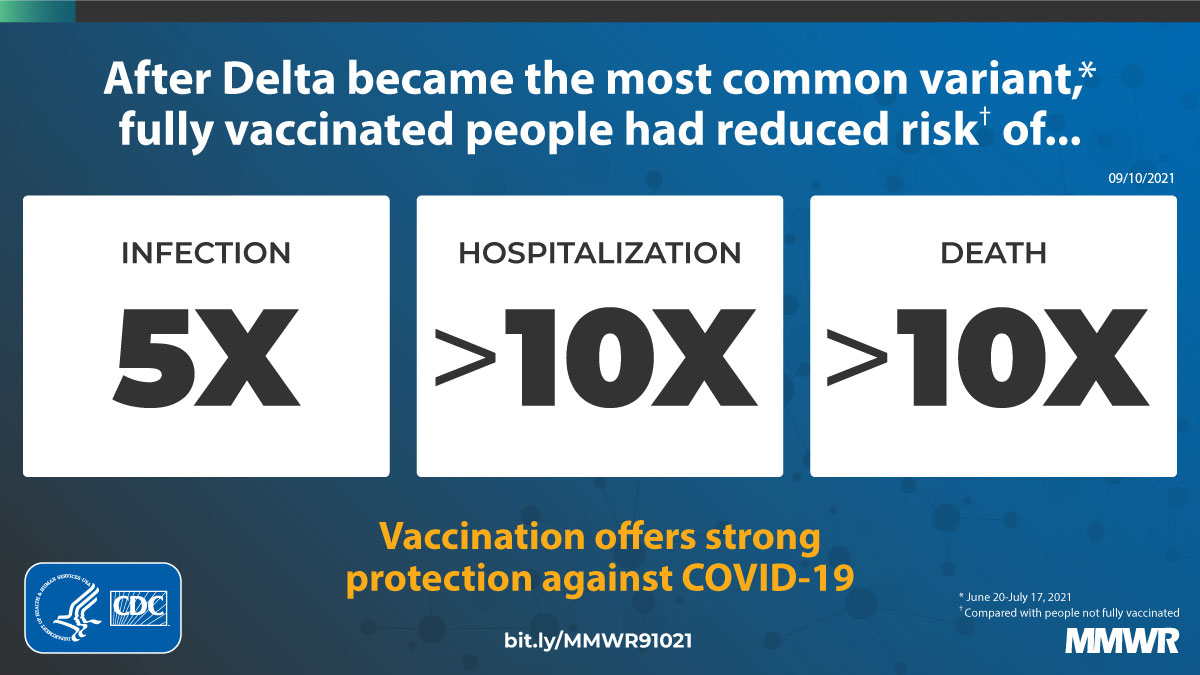

Scobie et al. Monitoring incidence of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, by vaccination status — 13 U.S. jurisdictions, April 4–July 17, 2021. -

Report mm7039e3 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-10-01;70(39):1377-1378.

Budzyn et al. Pediatric COVID-19 cases in counties with and without school mask requirements — United States, July 1–September 4, 2021. -

Report mm7041a2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-10-15;70(41):1441-1446.

Bohm et al. Binge drinking among adults, by select characteristics and state — United States, 2018. -

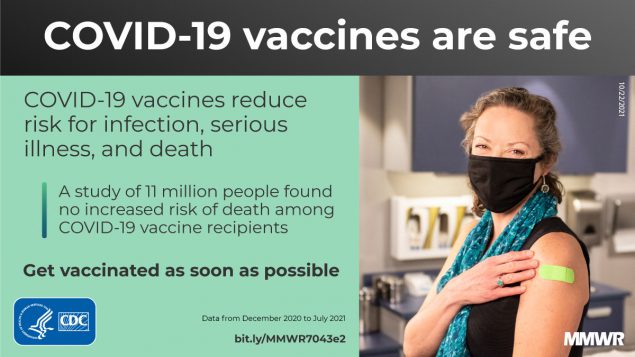

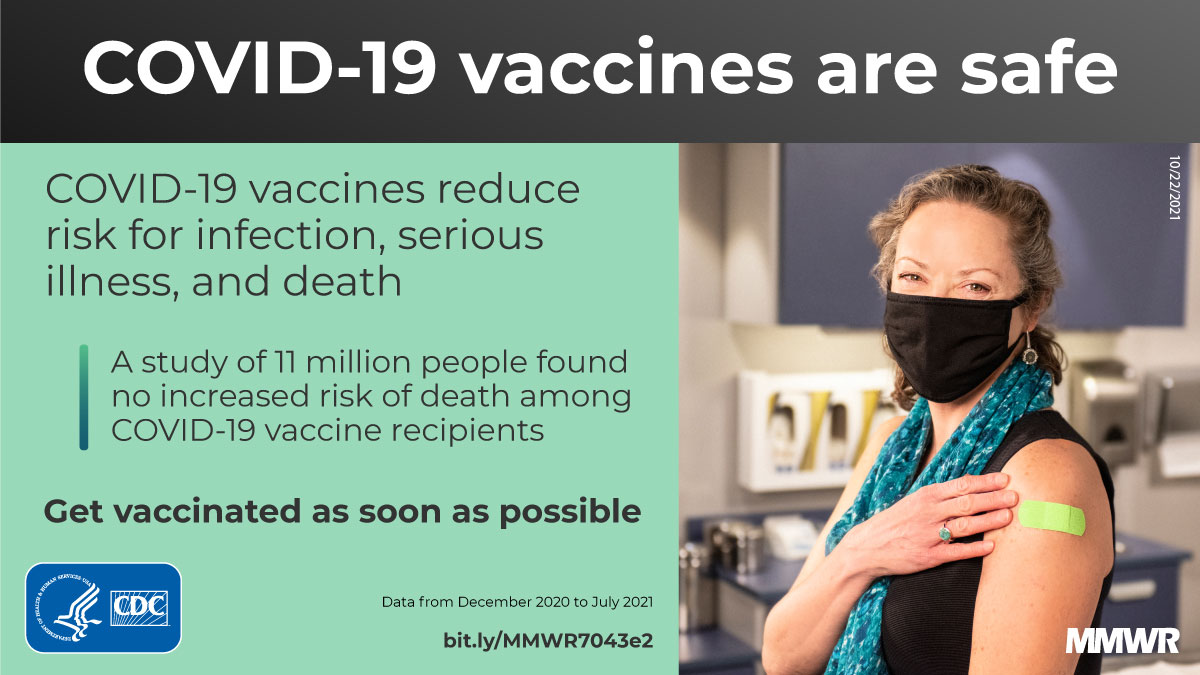

Report mm7043e2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-10-29;70(43):1520-1524.

Xu et al. COVID-19 Vaccination and non–COVID-19 mortality risk — seven integrated health care organizations, United States, December 14, 2020–July 31, 2021. -

Report mm7047e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-11-26;70(47):1640-1645.

DeSisto et al. Risk for stillbirth among women with and without COVID-19 at delivery hospitalization — United States, March 2020–September 2021. -

Report mm705152a2 (HTML PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-12-31;70(5152):1761-1765.

Lutrick et al. Interim estimate of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccine in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among adolescents aged 12–17 years — Arizona, July–December 2021. -

Report mm705152a3 (HTML PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2021-12-31;70(5152):1766-1772.

Wanga et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of children and adolescents aged 18 years hospitalized with COVID-19 — six hospitals, United States, July–August 2021. -

Report mm7104e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2022-01-28;71(4):125-131.

León et al. COVID-19 Cases and hospitalizations by COVID-19 vaccination status and previous COVID-19 diagnosis — California and New York, May–November 2021. -

Report mm7110e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2022-03-11;71(10):384-389.

Donovan et al. SARS-CoV-2 incidence in K–12 school districts with mask-required versus mask-optional policies — Arkansas, August–October 2021. -

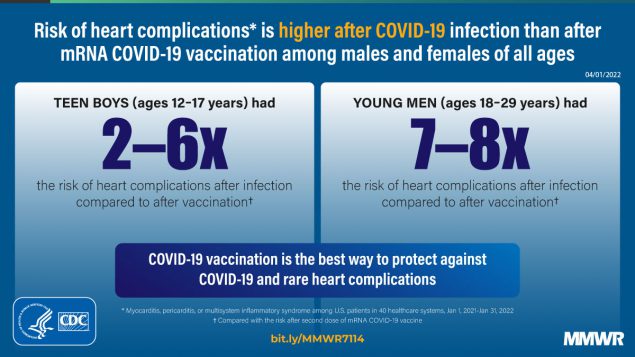

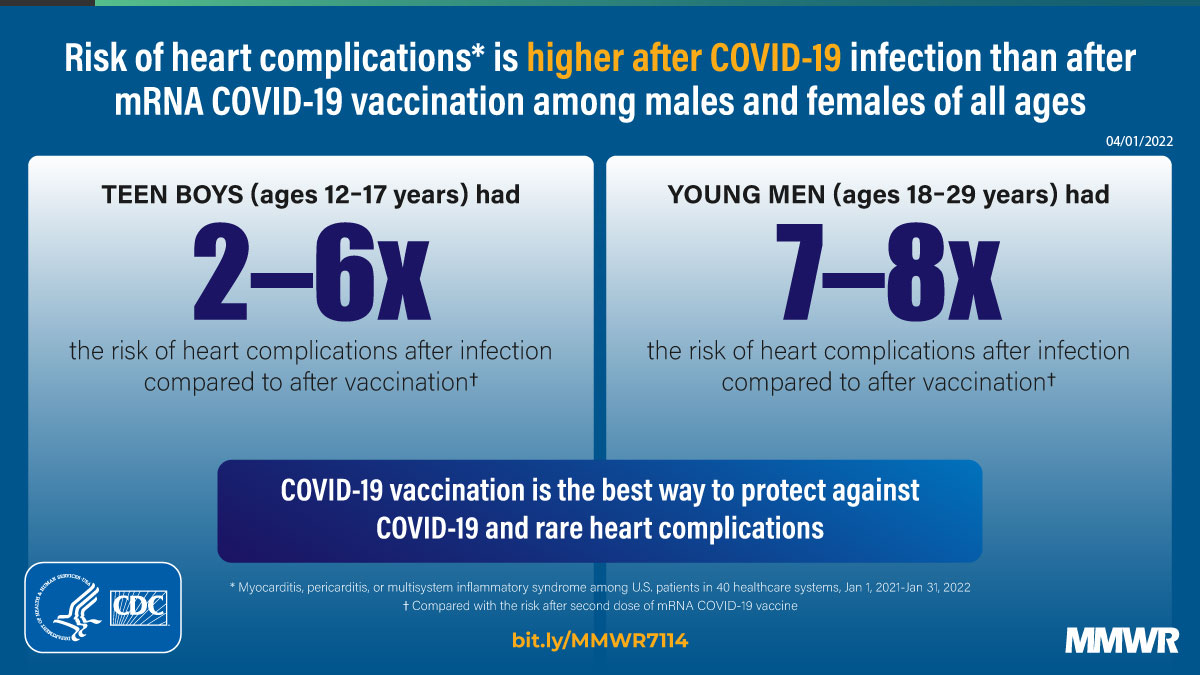

Report mm7114e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2022-04-08;71(14):517-523.

Block et al. Cardiac complications after SARS-CoV-2 infection and mRNA COVID-19 vaccination — PCORnet, United States, January 2021–January 2022. -

Report mm7121a2 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2022-05-27;71(21):703-708.

Sapkota et al. Seizure- or epilepsy-related emergency department visits before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, 2019–2021. -

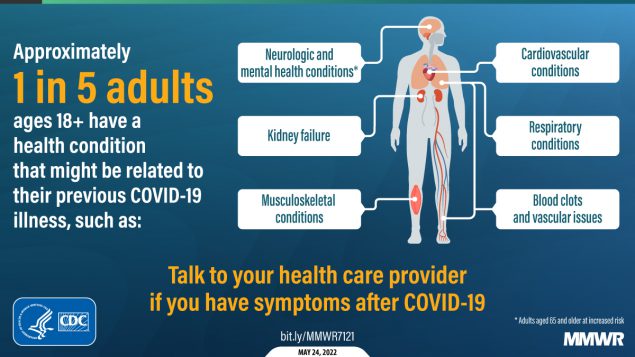

Report mm7121e1 (HTML | PDF1 | PDF2) MMWR. 2022-05-27;71(21):713-717.

Bull-Otterson et al. Post–COVID conditions among adult COVID-19 survivors aged 18–64 and ≥65 years — United States, March 2020–November 2021.

Opioid Prescribing Rates in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Counties Among Primary Care Providers Using an Electronic Health Record System — United States, 2014–2017 [mm6802a1]

Weekly / January 18, 2019 / 68(2);25–30

Macarena C. García, DrPH1; Charles M. Heilig, PhD1; Scott H. Lee, PhD1; Mark Faul, PhD2; Gery Guy, PhD2; Michael F. Iademarco, MD1; Katherine Hempstead, PhD3; Dorrie Raymond, MA4; Josh Gray, MBA4 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?

Opioid prescribing rates vary by county urbanization level and are declining overall.

What is added by this report?

Analysis of patient opioid prescription data from a national electronic health record vendor during 2014–2017 found that the percentage of patients prescribed an opioid was higher in rural than in urban areas. Significant decreases in opioid prescribing occurred across all urban-rural categories after the March 2016 release of the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain.

What are the implications for public health practice?

As less densely populated areas indicate both progress in decreasing opioid prescribing and need for ongoing reduction, tailoring community health care practices and intervention programs to community characteristics will remain important.

Drug overdose is the leading cause of unintentional injury-associated death in the United States. Among 70,237 fatal drug overdoses in 2017, prescription opioids were involved in 17,029 (24.2%) (1). Higher rates of opioid-related deaths have been recorded in nonmetropolitan (rural) areas (2). In 2017, 14 rural counties were among the 15 counties with the highest opioid prescribing rates.* Higher opioid prescribing rates put patients at risk for addiction and overdose (3). Using deidentified data from the Athenahealth electronic health record (EHR) system, opioid prescribing rates among 31,422 primary care providers† in the United States were analyzed to evaluate trends from January 2014 to March 2017. This analysis assessed how prescribing practices varied among six urban-rural classification categories of counties, before and after the March 2016 release of CDC’s Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain (Guideline) (4). Patients in noncore (the most rural) counties had an 87% higher chance of receiving an opioid prescription compared with persons in large central metropolitan counties during the study period. Across all six county groups, the odds of receiving an opioid prescription decreased significantly after March 2016. This decrease followed a flat trend during the preceding period in micropolitan and large central metropolitan county groups; in contrast, the decrease continued previous downward trends in the other four county groups. Data from EHRs can effectively supplement traditional surveillance methods for monitoring trends in opioid prescribing and other areas of public health importance, with minimal lag time under ideal conditions. As less densely populated areas appear to indicate both substantial progress in decreasing opioid prescribing and ongoing need for reduction, community health care practices and intervention programs must continue to be tailored to community characteristics.

Athenahealth is a commercial vendor and developer of cloud-based practice management and EHR systems for physician practices and hospitals. Approximately 100,000 health providers, serving about 86 million patients in the United States, use Athenahealth’s applications. This retrospective study used deidentified Athenahealth EHR prescription data from 31,422 primary health care providers serving approximately 17 million patients. Patient-level data were aggregated by week over the 166 weeks from January 5, 2014, through March 11, 2017. For each week during which a patient had at least one Athenahealth record, that patient contributed one patient-week to this analysis. For each patient-week, it was noted whether primary care providers using Athenahealth’s EHR system prescribed one or more opioids (Supplementary Table 1, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/61743).§ Percentage of patient-weeks during which an opioid prescription was written was considered equivalent to the percentage of patients receiving an opioid prescription during that time.

For comparisons over time, data were divided into three periods. Period 1 comprises 52 weeks from January 5, 2014, through January 3, 2015; period 2 includes the next 63 weeks, ending March 19, 2016; and period 3 covers the final 51 weeks, through March 11, 2017. The first cutpoint allows comparisons between the first and second years’ data, and the second cutpoint supports comparisons before and after the publication of the CDC Guideline. For comparison by population density, data were stratified by providers’ counties according to CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural classification scheme.¶ From most to least densely populated, the six categories include large central metropolitan, large fringe metropolitan, medium metropolitan, small metropolitan, micropolitan, and noncore counties.

This analysis includes three components. First, the period-specific percentage of patients with opioid prescriptions was estimated empirically and with seasonal adjustment using logistic regression. Second, smooth temporal trends were statistically separated from annual seasonal components using locally weighted regression (5). Third, to quantify the period-specific annual rate of increase or decrease in prescribing rates, a second logistic regression model estimated the seasonally adjusted annual percent change (APC) in the odds of receiving an opioid prescription. Statistical software was used for all analyses; statistical tests and confidence intervals (CIs) are presented as simultaneous procedures adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Overall, 128,194,491 patient-weeks of data are included in the analysis; at least one opioid was prescribed during 8,810,237 (6.9%) of these patient-weeks, decreasing from 7.4% during period 1 to 6.4% during period 3 (Table 1) (Supplementary Table 2, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/61744). Buprenorphine prescribed for pain and opioid use disorder treatment represented only 0.02% of all opioid prescriptions. By county classification, the overall percentage of patients with opioid prescriptions ranged from 5.2% in large central metropolitan counties to 9.6% in noncore counties during the study period. Patients in noncore counties had an 87% higher chance of receiving an opioid prescription than did patients in large central metropolitan areas during the study period.

The lowest period-specific percentages of patient-weeks with an opioid prescription occurred in large central metropolitan counties (5.0%–5.4%) (p<0.001, multiplicity-adjusted Wald tests), except during period 3, when percentages in large metropolitan counties (5.0%) were the same as those in large fringe metropolitan counties (5.0%) (Supplementary Table 2, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/61744). In contrast, the highest period-specific percentages (9.0%–10.3%) were in noncore counties (p<0.02), except in period 3, when percentages in noncore counties (9.0%) were similar to those in micropolitan counties (9.1%). Across metropolitan and nonmetropolitan categories, all percentages of weeks with an opioid prescription during period 2 were significantly different from those in period 1, and percentages in period 3 differed significantly from those in period 2 (p<0.003).

Visual inspection of the prescribing trends by urban-rural status and by period revealed patterns in both the raw (Supplementary Figure 1, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/61741) and seasonally adjusted (Supplementary Figure 2, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/61742) data. During period 1, before release of the CDC Guideline, the odds of receiving an opioid prescription increased 6.4% per year in noncore counties (95% multiplicity-adjusted Wald CI = 2.1–10.8), and 9.7% per year in micropolitan counties (95% CI = 6.5–13.0) (Table 2) (Figure). During period 3, after release of the CDC Guideline, the odds of receiving an opioid prescription decreased significantly in all county groups. Comparing trends between periods, the APC increased in large central metropolitan counties in period 2 compared with period 1 (p<0.001) and decreased between periods 2 and 3 (p<0.001). In the other five urban-rural categories, the APC decreased in period 2 compared with period 1 (p<0.02); among these five groups, only micropolitan counties experienced a significant decrease in APC between periods 2 and 3 (p<0.001).

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

Discussion

Throughout the analysis period, opioid prescribing rates by primary care providers were significantly higher in nonmetropolitan counties than in metropolitan counties. Whereas the prescribing rate increased from January 2014 through January 2015 (period 1) in both micropolitan and noncore counties, those trends halted, and rates became flat or declined through mid-March 2016 (period 2). Trends in all other urban-rural categories were flat or decreasing over the same two periods. The odds of a patient receiving an opioid prescription decreased in all urban-rural county groups after the March 2016 publication of the CDC Guideline. Those trends represented significant decreases in the micropolitan and large central metropolitan categories. In the other four county groups, however, the significant decreases after March 2016 represented a continuation of previously decreasing trends.

Higher odds of opioid prescribing in nonmetropolitan counties might be attributed in part to prescription drug use and misuse at an earlier age as well as higher prevalences of chronic pain among persons living in rural areas (6,7). Nonmetropolitan counties also tend to have larger populations of older adults who have higher prevalences of conditions associated with pain (6). Opioid prescribing in rural (nonmetropolitan) areas is strongly influenced by providers’ individual relationships with their patients (8), and can be inconsistent with opioid prescribing guidelines. As well, access to medication-assisted treatment facilities and alternative therapies are limited in rural areas (8). Variations in the implementation of state-run prescription drug monitoring programs and state-based laws (9), such as the regulation of pain-management clinics, might also differ in urban and rural communities.

Despite reductions in opioid prescribing in recent years (1), opioid-involved overdose death rates have increased, largely driven by heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl (2). Many persons who self-report heroin use have a history of misusing prescription opioids (10). Addressing prescription opioid use is an important step in curbing opioid-involved overdose deaths. Interventions such as using Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs and practices that align with evidence-based adoption of the CDC Guideline can improve prescribing decisions.** The Guideline can help providers and patients weigh the benefits and risks of prescribing opioids according to best available evidence and individual patient needs (4). This study demonstrates that data from EHRs can effectively supplement traditional surveillance methods for monitoring trends in opioid prescribing and other areas of public health importance. The lag between the collection of the data and this analysis could potentially be reduced to a matter of weeks with optimized workflows.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, the conclusions drawn from the records provided by Athenahealth might not be generalizable to all patients in primary care. Second, although the data include all patients with an opioid prescription, they do not include other characteristics of each prescription, including indication (e.g., chronic versus acute pain or opioid use disorder treated with buprenorphine [although this drug accounted for a small fraction of all opioids prescribed]) and whether prescriptions were filled and taken as prescribed. Finally, this analysis does not account for differing demographic profiles across counties, such as age distributions and payer types, which could be confounded by population density in its association with opioid prescribing rates.

The percentage of patients who received an opioid prescription was lower in more densely populated counties than among less populated rural counties; however, all areas, including rural counties, experienced substantial decreases in prescribing over time. As less densely populated areas appear to indicate both substantial progress in decreasing opioid prescribing and ongoing need for reduction, community health care practices and intervention programs must continue to be tailored to community characteristics.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

Corresponding author: Macarena C. García, mcgarcia@cdc.gov, 404-539-4410.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

1Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC; 2National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC; 3Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey; 4Athenahealth, AthenaResearch, Watertown, Massachusetts.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

* U.S. Opioid Prescribing Rate Maps. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html.

† Primary care providers in an ambulatory setting; limited to family medicine, family practice, or general practice, or providers who have an internal medicine specialty with no subspecialty. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are included among primary care providers.

§ Short and long acting opioid drugs in this study included buprenorphine, butorphanol, codeine, dihydrocodeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, levorphanol, meperidine, methadone, morphine, naltrexone, nalbuphine, naloxone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, pentazocine, propoxyphene, tapentadol, and tramadol. The study does not count cough and cold medications containing opioids.

¶ https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_166.pdf.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

References

- Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1419–27. CrossRef PubMed

- Mack KA, Jones CM, Ballesteros MF. Illicit drug use, illicit drug use disorders, and drug overdose deaths in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas—United States. Am J Transplant 2017;17:3241–52. CrossRef PubMed

- CDC. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1487–92. PubMed

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-1). CrossRef PubMed

- Cleveland RB, Cleveland WS, McRae JE, Terpenning I. STL: a seasonal-trend decomposition procedure based on loess. J Off Stat 1990;6:3–33.

- Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Brady JE, Havens JR, Galea S. Understanding the rural-urban differences in nonmedical prescription opioid use and abuse in the United States. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e52–9. CrossRef PubMed

- Monnat SM, Rigg KK. Examining rural/urban differences in prescription opioid misuse among US adolescents. J Rural Health 2016;32:204–18. CrossRef PubMed

- Click IA, Basden JA, Bohannon JM, Anderson H, Tudiver F. Opioid prescribing in rural family practices: a qualitative study. Subst Use Misuse 2018;53:533–40. CrossRef PubMed

- Rutkow L, Chang HY, Daubresse M, Webster DW, Stuart EA, Alexander GC. Effect of Florida’s prescription drug monitoring program and pill mill laws on opioid prescribing and use. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1642–9. CrossRef PubMed

- Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med 2016;374:154–63. CrossRef PubMed

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

* National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural classification scheme for counties. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm.

† Period 1: January 5, 2014–January 3, 2015; period 2: January 4, 2015–March 19, 2016; period 3: March 20, 2016–March 11, 2017. Period-specific percentages are based on raw counts rather than statistical models.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

* National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural classification scheme for counties. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm.

† Period 1: January 5, 2014–January 3, 2015; period 2: January 4, 2015–March 19, 2016; period 3: March 20, 2016–March 11, 2017.

§ p-values from multiplicity-adjusted Wald tests; (—) indicates a nonsignificant difference (p>0.05) between APCs in adjacent periods.

¶ p<0.001.

** p<0.05.

†† p<0.01.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

FIGURE. Model-based trends in percentage of patient-weeks with at least one opioid prescription, by urban-rural category — Athenahealth, United States, January 2014–March 2017

[ Top of page | Top of mm6802a1 ]

Suggested citation for this article: García MC, Heilig CM, Lee SH, et al. Opioid Prescribing Rates in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Counties Among Primary Care Providers Using an Electronic Health Record System — United States, 2014–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:25–30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6802a1.

Interim Estimates of 2018–19 Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness — United States, February 2019 [mm6806a2]

Weekly / February 15, 2019 / 68(6);135–139

Joshua D. Doyle, MD, PhD1,2; Jessie R. Chung, MPH2; Sara S. Kim, MPH2; Manjusha Gaglani, MBBS3; Chandni Raiyani, MPH3; Richard K. Zimmerman, MD4; Mary Patricia Nowalk, PhD4; Michael L. Jackson, PhD5; Lisa A. Jackson, MD5; Arnold S. Monto, MD6; Emily T. Martin, PhD6; Edward A. Belongia, MD7; Huong Q. McLean, PhD7; Angie Foust, MS2; Wendy Sessions, MPH2; LaShondra Berman, MS2; Rebecca J. Garten, PhD2; John R. Barnes, PhD2; David E. Wentworth, PhD2; Alicia M. Fry, MD2; Manish M. Patel, MD2; Brendan Flannery, PhD2 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?

Annual vaccination against seasonal influenza is recommended for all U.S. persons aged ≥6 months. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine varies by season.

What is added by this report?

On the basis of data from the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network on 3,254 children and adults with acute respiratory illness during November 23, 2018–February 2, 2019, the overall estimated effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine for preventing medically attended, laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection was 47%.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Vaccination remains the best way to protect against influenza and its potentially serious complications. CDC continues to recommend influenza vaccination while influenza viruses are circulating in the community.

- pdf icon [PDF]

In the United States, annual vaccination against seasonal influenza is recommended for all persons aged ≥6 months (https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/whoshouldvax.htm). Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine varies by season. During each influenza season since 2004–05, CDC has estimated the effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine to prevent laboratory-confirmed influenza associated with medically attended acute respiratory illness (ARI). This interim report uses data from 3,254 children and adults enrolled in the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (U.S. Flu VE Network) during November 23, 2018–February 2, 2019. During this period, overall adjusted vaccine effectiveness against all influenza virus infection associated with medically attended ARI was 47% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 34%–57%). For children aged 6 months–17 years, overall vaccine effectiveness was 61% (44%–73%). Seventy-four percent of influenza A infections for which subtype information was available were caused by A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses. Vaccine effectiveness was estimated to be 46% (30%–58%) against illness caused by influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses. CDC recommends that health care providers continue to administer influenza vaccine because influenza activity is ongoing and the vaccine can still prevent illness, hospitalization, and death associated with currently circulating influenza viruses, or other influenza viruses that might circulate later in the season. During the 2017–18 influenza season, in which influenza A(H3N2) predominated, vaccination was estimated to prevent 7.1 million illnesses, 3.7 million medical visits, 109,000 hospitalizations, and 8,000 deaths (1). Vaccination can also reduce the severity of influenza-associated illness (2). Persons aged ≥6 months who have not yet been vaccinated this season should be vaccinated.

Methods used by the U.S. Flu VE Network have been published previously (3). At five study sites (Michigan, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin), patients aged ≥6 months seeking outpatient medical care for an ARI with cough within 7 days of illness onset were enrolled. Study enrollment began after local surveillance identified increasing weekly influenza activity or one or more laboratory-confirmed cases of influenza per week for 2 consecutive weeks. Patients were eligible for enrollment if they met the following criteria: 1) were aged ≥6 months on September 1, 2018, and thus eligible for vaccination; 2) reported an ARI with cough with onset ≤7 days; and 3) had not been treated with influenza antiviral medication (e.g., oseltamivir) during this illness. After obtaining informed consent from patients or their guardians, participants or their proxies were interviewed to collect demographic data, information on general and current health status and symptoms, and 2018–19 influenza vaccination status. Nasal and oropharyngeal swabs (or nasal swabs alone for children aged <2 years) were collected to obtain respiratory specimens. Nasal and oropharyngeal swabs were placed together in a single tube of viral transport medium and tested at U.S. Flu VE Network laboratories using CDC’s real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (real-time RT-PCR) protocol for detection and identification of influenza viruses. Participants (including children aged <9 years, who require 2 vaccine doses during their first vaccination season) were considered vaccinated if they received ≥1 dose of any seasonal influenza vaccine ≥14 days before illness onset, according to medical records and registries (at the Wisconsin site); medical records and self-report (at the Pennsylvania, Texas, and Washington sites); or self-report only (at the Michigan site). Vaccine effectiveness against all influenza virus types combined and against viruses by type/subtype was estimated as 100% x (1 – odds ratio).* Estimates were adjusted for study site, age group, sex, race/ethnicity, self-rated general health, number of days from illness onset to enrollment, and month of illness (4-week intervals) using logistic regression. Interim vaccine effectiveness estimates for the 2018–19 season were based on patients enrolled through February 2, 2019.

Among the 3,254 children and adults with ARI enrolled at the five study sites from November 23, 2018, through February 2, 2019, a total of 465 (14%) tested positive for influenza virus by real time RT-PCR, including 456 (98%) for influenza A viruses and nine (2%) for influenza B viruses (Table 1). Among 394 subtyped influenza A viruses, 293 (74%) were A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, and 101 (26%) were A(H3N2) viruses. Of the eight influenza B viruses with lineage information available, four belonged to the B/Victoria lineage and four belonged to the B/Yamagata lineage. The proportion of patients with influenza differed by study site, age group, self-rated health status, and interval from illness onset to enrollment. The percentage of all ARI patients who were vaccinated ranged from 46% to 61% among study sites and differed by study site, sex, age group, race/ethnicity, and interval from illness onset to enrollment.

Among participants, 43% of those with influenza had received the 2018–19 seasonal influenza vaccine, compared with 57% of influenza-negative participants (Table 2). The adjusted vaccine effectiveness against medically attended ARI caused by all influenza virus types combined was 47% (95% CI = 34%–57%). Vaccine effectiveness for all ages was 46% (30%–58%) against medically attended ARI caused by A(H1N1)pdm09 virus infection and 44% (13%–64%) against influenza A(H3N2) virus infection. Among children aged 6 months–17 years, vaccine effectiveness against all influenza virus types was 61% (44%–73%), and effectiveness against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 was 62% (40%–75%). Among adults ≥50 years, vaccine effectiveness against all influenza types and influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 was 24%(-15% to 51%) and 8% (-59% to 46%), respectively; neither were significant.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

Discussion

Influenza activity remains elevated in the United States (4). Overall, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses have predominated in most of the country, although circulation of influenza A(H3N2) and low levels of influenza B viruses have also been observed. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in reducing the risk for medically attended influenza illness has ranged from approximately 40%–60% across all ages during seasons when most circulating influenza viruses are antigenically like the recommended influenza vaccine components. The overall interim estimate of 47% vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in all age groups is similar to that observed during the most recent A(H1N1)pdm09 predominant season (45%) in 2015–16 (3), but lower than a meta-analysis of vaccine effectiveness against A(H1N1)pdm09 since the 2010–11 season in the United States (5). This interim estimate also is lower than the recently reported interim estimates of 72% effectiveness against A(H1N1)pdm09 in Canada during the 2018–19 season (6) and 78% against A(H1N1)pdm09 in Australia during the 2018 Southern Hemisphere influenza season (7). The reasons for these differences might include limited sample size caused by low attack rates in some age groups, geographic differences in circulating viruses, and genetic variation within virus subtypes (4). Of note, vaccine effectiveness against A(H1N1)pdm09 among children and adolescents aged 6 months–17 years (62%) was similar to that observed during the 2015–16 season in this age group (49%–63%) (3). Among adults aged ≥50 years, interim estimates of effectiveness were not significant. Vaccine effectiveness against A(H3N2) virus infection was 44% (95% CI = 13%–64%) but a limited number of A(H3N2) viruses were detected. Several more weeks of influenza are likely, and CDC continues to recommend influenza vaccination while influenza viruses are circulating in the community. Vaccination can protect against infection with influenza viruses that are currently circulating, as well as those that may circulate later in the season.

Vaccination remains the best method for preventing influenza and its potentially serious complications, including those that can result in hospitalization and death. In particular, vaccination has been found to reduce the risk for influenza-associated deaths in children (8). During past seasons, including the 2017–18 season, approximately 80% of reported pediatric influenza-associated deaths have occurred in children who were not vaccinated. Vaccination also has been found to reduce the risk for influenza-associated hospitalization in pregnant women (9) and can reduce the risk for cardiac events among persons with heart disease (10). CDC recommends antiviral treatment for any patient with suspected or confirmed influenza who is hospitalized, has severe or progressive illness, or is at high risk for complications from influenza, regardless of vaccination status or results of point-of-care influenza diagnostic tests.† Antiviral treatment also can be considered for any previously healthy symptomatic outpatient not at high risk for complications, with confirmed or suspected influenza, if treatment can be started within 48 hours of illness onset.

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, sample sizes are smaller than in recent interim reports, resulting in wide confidence intervals, particularly in adults aged ≥50 years. The small sample size also limits the number of age groups included in this analysis. This limitation is common among interim vaccine effectiveness reports during mild or late influenza seasons. End-of-season vaccine effectiveness estimates could change as additional patient data become available or if a change in circulating viruses occurs later in the season. Second, vaccination status included self-report at four of five sites; end-of-season vaccine effectiveness estimates based on updated documentation of vaccination status might differ from interim estimates. For this reason, the type of vaccine received by participants (e.g., egg-based, cell culture–based, or recombinant antigen) is not available at this time, although this information will be updated at the end of the season. Third, an observational study design has greater potential for confounding and bias than do randomized clinical trials. However, the test-negative design is widely used in vaccine effectiveness studies and has been used by the U.S. Flu VE Network to estimate vaccine effectiveness for previous influenza seasons. Finally, the vaccine effectiveness estimates in this report are limited to the prevention of outpatient medical visits rather than more severe illness outcomes, such as hospitalization or death; data from studies measuring vaccine effectiveness against more severe outcomes will be available at a later date.

Vaccination prevents a substantial number of influenza-related illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths annually. However, better protection and improved vaccination coverage are needed to realize the full potential of influenza vaccines. Evaluation of influenza vaccine effectiveness is an essential component of ongoing efforts to improve influenza vaccines. Influenza activity remains elevated in the United States, highlighting the importance of vaccination. CDC will continue to monitor influenza disease throughout the season to better understand the impact of vaccination, identify factors associated with reduced protection, and support efforts to improve influenza vaccines.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

Acknowledgments

Alejandro Arroliga, Madhava Beeram, Kelsey Bounds, Wencong Chen, Lydia Clipper, Renee Day, Amanda Drake, Mary Kylberg, Michael Smith, Kempapura Murthy, Teresa Ponder, Michael Reis, Natalie Settele, Jennifer Thomas, Jamie Walkowiak, patients and staff from all participating clinics, Baylor Scott & White Health and Texas A&M University Health Science Center College of Medicine, Temple, Texas; Rose Azrak, G.K. Balasubramani, Todd M. Bear, Duane Eisaman, Heather Eng, Andrew Fackler, Edward Garofolo, Robert Hickey, Philip Iozzi, Monika Johnson, Stephanie Kirk, Jason A. Lyons, Donald B. Middleton, Krissy K. Moehling, Jonathan M. Raviotta, Evelyn C. Reis, Bret Rosenblum, Sean Saul, Theresa Sax, Michael Susick, Joe Suyama, Leonard F. Urbanski, Alexandra Weissman, John V. Williams, University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Zoe Kappelman, Erika Kiniry, Lawrence Madziwa, Matt Nguyen, Suzie Park, C. Hallie Phillips, Stacie Wellwood, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, Washington; Allen Achkar, Elizabeth Alleman, Trinh Anh Minh, Habeeb Al-Shohatee, Gabriela Augustinaitis, Sarah Bauer, Danielle Carroll, Caroline K. Cheng, Robert Deblander III, Michelle Groesbeck, Emileigh Johnson, Anne Kaniclides, Armanda Kimberly, Jenna Kiryakos, Marym Kuril, Lois E. Lamerato, Ryan E. Malosh, Maria Matta, E.J. McSpadden, Madeleine Mendelow, Joshua G. Petrie, Niharika Rajesh, Bryan Richardson, Stephanie Robinson, Hannah Segaloff, Caleb Sokolowski, Rachael Swanson, Rachel Truscon, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan; Elizabeth Armagost, Theresa Balinghasay, Tamara Braund, Deanna Cole, Carrie Curtis, Tom Dalcher, Alicia Easley, Terry Foss, Wayne Frome, Hannah Gourdoux, Gregg Greenwald, Sherri Guzinski, Kayla Hanson, Linda Heeren, Lynn Ivacic, Marie Janz, Tara Johnson, Julie Karl, Jennifer King, Tamara Kronenwetter Koepel, Diane Kohnhorst, Sarah Kopitzke, Erik Kronholm, Marcia Lichtenwald, Carrie Marcis, Karen McGreevey, Jennifer Meece, Nidhi Mehta, Vicki Moon, Madalyn Palmquist, Nan Pan, Rebecca Pilsner, DeeAnn Polacek, Martha Presson, Lauren Putnam, Carla Rottscheit, Crystal Sabatke, Jacklyn Salzwedel, Megan Sauer, Julian Savu, Ram Shrestha, Elisha Stefanski, Patrick Stockwell, Sandy Strey, Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, Marshfield, Wisconsin; Juliana DaSilva, Shoshona Le, Thomas Stark, Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

Corresponding author: Joshua D. Doyle, JDoyle2@cdc.gov, 404-718-6818.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

1Epidemic Intelligence Service, CDC; 2Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; 3Baylor Scott & White Health, Texas A&M University Health Science Center College of Medicine, Temple, Texas; 4University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 5Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, Washington; 6University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, Michigan; 7Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, Marshfield, Wisconsin.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Richard Zimmerman reports grants from Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, and Merck & Co., outside the submitted work; Arnold S. Monto reports personal fees from Sanofi Pasteur and Seqirus, outside the submitted work; Emily T. Martin reports personal fees from Pfizer, outside the submitted work; Michael L. Jackson reports grants from Sanofi Pasteur, outside the submitted work; Mary Patricia Nowalk reports grants from Merck & Co, Inc. and Pfizer, outside the submitted work; and Huong Q. McLean reports grants from Seqirus, outside the submitted work. No other potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

* 100% x (1 – odds ratio [ratio of odds of being vaccinated among outpatients with influenza-positive test results to the odds of being vaccinated among outpatients with influenza-negative test results]).

† A complete summary of guidance for antiviral use is available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Groups at high risk for influenza complications include the following: children aged <2 years; adults aged ≥65 years; persons with chronic pulmonary conditions (including asthma); persons with cardiovascular disease (except hypertension alone); persons with renal, hepatic, or hematologic (including sickle cell) disease; persons with metabolic disorders (including diabetes mellitus); persons with neurologic and neurodevelopmental conditions (including disorders of the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves and muscles, such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy [seizure disorders], stroke, intellectual disability [mental retardation], moderate to severe developmental delay, muscular dystrophy, or spinal cord injury); persons with immunosuppression, including that caused by medications or by human immunodeficiency virus infection; women who are pregnant or ≤2 weeks postpartum; persons aged <19 years who are receiving long-term aspirin or salicylate-containing medications; American Indian/Alaska Natives; persons with morbid obesity (i.e., body-mass index ≥40); and residents of nursing homes and other chronic-care facilities.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

References

- Rolfes MA, Flannery B, Chung J, et al. Effects of influenza vaccination in the United States during the 2017–2018 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis 2019. Epub February 2, 2019.

- Arriola C, Garg S, Anderson EJ, et al. Influenza vaccination modifies disease severity among community-dwelling adults hospitalized with influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:1289–97. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Jackson ML, Chung JR, Jackson LA, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during the 2015–2016 season. N Engl J Med 2017;377:534–43. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Blanton L, Dugan VG, Elal AIA, et al. Update: influenza activity—United States, September 30, 2018–February 2, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:125–34.

- Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP, et al. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:942–51. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Skowronski DM, Leir S, Sabaiduc S, et al. Interim estimates of 2018/19 vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, Canada, January 2019. Euro Surveill 2019;24:1900055. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Australian Government Department of Health. Information brief: 2018 influenza season in Australia. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health; 2016. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-surveil-ozflu-flucurr.htm/$File/2018-Season-Summary.pdfpdf iconexternal icon

- Flannery B, Reynolds SB, Blanton L, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against pediatric deaths: 2010–2014. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20164244. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Thompson MG, Kwong JC, Regan AK, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy: a multi-country retrospective test negative design study, 2010–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2018. Epub October 11, 2018.

- Udell JA, Zawi R, Bhatt DL, et al. Association between influenza vaccination and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk patients: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2013;310:1711–20. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

* Sex was unknown for one patient, race/ethnicity for 11 patients, and self-rated health status for two patients.

† Defined as having received ≥1 dose of influenza vaccine ≥14 days before illness onset. A total of 78 participants who received the vaccine ≤13 days before illness onset were excluded from the study sample.

§ The chi-square statistic was used to assess differences between the numbers of persons with influenza-negative and influenza-positive test results, in the distribution of enrolled patient and illness characteristics, and in differences between groups in the percentage vaccinated.

¶ Patients were categorized into one of four mutually exclusive racial/ethnic populations: white, black, other race, and Hispanic. Persons identifying as Hispanic might have been of any race. Persons identifying as white, black, or other race were non-Hispanic.

** Percentage for which lineage information was available (n = 8).

†† Percentage for which subtype information was available (n = 394).

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

* Vaccine effectiveness was estimated as 100% x (1 – odds ratio [ratio of odds of being vaccinated among outpatients with influenza-positive test results to the odds of being vaccinated among outpatients with influenza-negative test results]); odds ratios were estimated using logistic regression.

† Adjusted for study site, age group, sex, race/ethnicity, self-rated general health, number of days from illness onset to enrollment, and month of illness (4-week intervals) using logistic regression.

§ Statistically significant at p<0.05.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6806a2 ]

Suggested citation for this article: Doyle JD, Chung JR, Kim SS, et al. Interim Estimates of 2018–19 Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness — United States, February 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:135–139. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6806a2external icon.

Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Cocaine and Psychostimulants with Abuse Potential — United States, 2003–2017 [mm6817a3]

Weekly / May 3, 2019 / 68(17);388–395

Mbabazi Kariisa, PhD1; Lawrence Scholl, PhD1; Nana Wilson, PhD1; Puja Seth, PhD1; Brooke Hoots, PhD1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?

Overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants continue to increase. During 2015–2016, age-adjusted cocaine-involved and psychostimulant-involved death rates increased by 52.4% and 33.3%, respectively.

What is added by this report?

From 2016 to 2017, death rates involving cocaine and psychostimulants increased across age groups, racial/ethnic groups, county urbanization levels, and multiple states. Death rates involving cocaine and psychostimulants, with and without opioids, have increased. Synthetic opioids appear to be the primary driver of cocaine-involved death rate increases, and recent data point to increasing synthetic opioid involvement in psychostimulant-involved deaths.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Continued increases in stimulant-involved deaths require expanded surveillance and comprehensive, evidence-based public health and public safety interventions.

- pdf icon [PDF]

In 2016, a total of 63,632 persons died from drug overdoses in the United States (1). Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine, psychostimulants with abuse potential (psychostimulants), or both substances combined increased 42.4% from 12,122 in 2015 to 17,258 in 2016.* Psychostimulants with abuse potential include drugs such as methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), dextroamphetamine, levoamphetamine, methylphenidate (Ritalin), and caffeine. From 2015 to 2016, cocaine-involved and psychostimulant-involved death rates increased 52.4% and 33.3%, respectively (1). A total of 70,237 persons died from drug overdoses in the United States in 2017; approximately two thirds of these deaths involved an opioid (2). CDC analyzed 2016–2017 changes in age-adjusted death rates involving cocaine and psychostimulants by demographic characteristics, urbanization levels, U.S. Census region, 34 states, and the District of Columbia (DC). CDC also examined trends in age-adjusted cocaine-involved and psychostimulant-involved death rates from 2003 to 2017 overall, as well as with and without co-involvement of opioids. Among all 2017 drug overdose deaths, 13,942 (19.8%) involved cocaine, and 10,333 (14.7%) involved psychostimulants. Death rates increased from 2016 to 2017 for both drug categories across demographic characteristics, urbanization levels, Census regions, and states. In 2017, opioids were involved in 72.7% and 50.4% of cocaine-involved and psychostimulant-involved overdoses, respectively, and the data suggest that increases in cocaine-involved overdose deaths from 2012 to 2017 were driven primarily by synthetic opioids. Conversely, increases in psychostimulant-involved deaths from 2010 to 2017 occurred largely independent of opioids, with increased co-involvement of synthetic opioids in recent years. Provisional data from 2018 indicate that deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants are continuing to increase.† Increases in stimulant-involved deaths are part of a growing polysubstance landscape. Increased surveillance and evidence-based multisectoral prevention and response strategies are needed to address deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants and opioids. Enhancing linkage to care, building state and local capacity, and public health/public safety collaborations are critical components of prevention efforts.

Drug overdose deaths were identified in the National Vital Statistics System multiple cause-of-death mortality files,§ using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) underlying cause-of-death codes X40–X44 (unintentional), X60–X64 (suicide), X85 (homicide), or Y10–Y14 (undetermined intent). Among deaths with drug overdose as the underlying cause, the type of drug is indicated by the following ICD-10 multiple cause-of-death codes: cocaine (T40.5); psychostimulants with abuse potential (T43.6); opioids (T40.0–T40.4, and T40.6)¶; and synthetic opioids other than methadone (T40.4). Some deaths involved more than one type of drug; these deaths were included in the rates for each drug category. Thus, categories were not mutually exclusive.**

Age-adjusted death rates†† were examined for the period 2016– 2017 for cocaine and psychostimulants. Death rates were stratified by age group, sex, race/ethnicity, urbanization level,§§ U.S. Census region,¶¶ and state. State-level analyses were conducted for 34 states and DC, all of which had adequate drug-specificity data recorded on death certificates for 2016 and 2017.*** Analyses comparing changes in death rates from 2016 to 2017 used z-tests when deaths were ≥100 and nonoverlapping confidence intervals based on a gamma distribution when deaths were <100.††† Trends in age-adjusted cocaine-involved and psychostimulant-involved death rates from 2003 to 2017 were analyzed overall, and with and without any opioids and synthetic opioids, using Joinpoint regression.§§§ Changes presented represent statistically significant findings unless otherwise specified.

In 2017, among 70,237 drug overdose deaths that occurred in the United States, 13,942 (19.8%) involved cocaine, representing a 34.4% increase from 2016 (Table). Nearly three fourths (72.7%) of cocaine-involved deaths in 2017 also involved opioids. Cocaine-involved death rates increased among both sexes and among persons aged ≥15 years, non-Hispanic whites (whites), non-Hispanic blacks (blacks), and Hispanics. The largest relative rate change occurred among females aged 15–24 years (40.0%), and the largest absolute rate change was among males aged 25–44 and 45–64 years (increase of 2.7 per 100,000). Among racial/ethnic groups, the highest rate of cocaine-involved deaths in 2017 occurred in blacks (8.3 per 100,000), who also experienced the largest relative rate change (36.1%) compared with 2016. By urban-rural status, counties in medium metro areas experienced the largest absolute rate increase (1.3 per 100,000) in 2017, whereas the largest relative rate increase occurred in micropolitan counties (57.9%). The Midwest Census region had the largest relative rate increase (43.6%), whereas the highest 2017 rate was in the Northeast (7.0 per 100,000). Death rates involving cocaine increased in 15 states, with the largest relative increases in Wisconsin (84.6%) and Maryland (72.0%), and the largest absolute rate increases in Ohio (3.9) and Maryland (3.6). In 2017, the highest death rates were in DC (17.6) and Ohio (14.0).

During 2003–2017, rates for all cocaine-involved deaths peaked initially in 2006, decreased during 2006–2012, and increased again during 2012–2017. Rates of overdose deaths involving cocaine and any opioid increased from 2013 to 2017, and those involving cocaine and synthetic opioids increased from 2012 to 2017 (Figure 1). Cocaine-involved death rates without any opioid decreased from 2006 to 2012 and then increased from 2012 to 2017, whereas cocaine-involved death rates without synthetic opioids increased from 2003 to 2006, decreased from 2006 to 2010, and then increased from 2010 to 2017 (Figure 1).

In 2017, a total of 10,333 deaths involving psychostimulants occurred, representing 14.7% of drug overdose deaths and a 37.0% increase from 2016 (Table). During 2016–2017, the age-adjusted rate for psychostimulant-involved deaths increased by 33.3%. Approximately half (50.4%) of psychostimulant-involved deaths also involved opioids in 2017. Psychostimulant-involved death rates increased among both sexes and among persons aged ≥15 years, whites, blacks, non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN), non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islanders (A/PI), and Hispanics. The largest relative rate increase occurred among females aged 25–44 years (48.0%). Among racial/ethnic groups, the largest relative rate increase occurred among whites (40.0%), whereas AI/AN experienced the largest absolute rate increase (1.6 per 100,000) and the highest death rate (8.5) in 2017. Counties in medium metro areas experienced the largest absolute rate increase (1.3 per 100,000), and the largest relative rate increase (46.4%). Among Census regions, both the largest relative increase (63.2%) and the largest absolute rate increase (1.2) occurred in the Midwest, whereas the highest psychostimulant-involved death rate (5.3) occurred in the West. Death rates increased in 17 states, with the largest relative increases in Ohio (130.4%) and West Virginia (94.3%), and the largest absolute rate increases in West Virginia (6.6 per 100,000) and Kentucky (3.3). In 2017, the highest death rates were in West Virginia (13.6 per 100,000) and Alaska (9.1).

During 2003–2017, rates for all psychostimulant-involved deaths increased from 2010 to 2017. Death rates involving psychostimulants and any opioid increased from 2003 to 2010, followed by sharper increases from 2010 to 2015 and from 2015 to 2017. Death rates involving psychostimulants and synthetic opioids increased from 2010 to 2015, followed by a sharper increase from 2015 to 2017 (Figure 2). Rates of psychostimulant-involved deaths without any opioid involvement increased from 2008 to 2017, and rates without synthetic opioid involvement increased from 2008 to 2017 (Figure 2).

[ Top of page | Top of mm6817a3 ]

Discussion

Deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants have increased in the United States in recent years; among 70,237 drug overdose deaths in 2017, nearly a third (23,139 [32.9%]) involved cocaine, psychostimulants, or both. From 2016 to 2017, death rates involving cocaine and psychostimulants each increased by approximately one third, and increases occurred across all demographic groups, Census regions, and in several states. In 2017, nearly three fourths of cocaine-involved and roughly one half of psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths, respectively, involved at least one opioid. After initially peaking in 2006, trends in overall cocaine-involved death rates declined through 2012, when they began to rise again. The 2006–2012 decrease paralleled a decline in cocaine supply coupled with an increase in cost.¶¶¶ Similar patterns in death rates involving both cocaine and opioids were observed, with increases for cocaine- and synthetic opioid-involved deaths occurring from 2012 to 2017. From 2010 to 2017, increasing rates of deaths involving psychostimulants occurred and persisted even in the absence of opioids. Drug overdoses continue to evolve along with emerging threats, changes in the drug supply, mixing of substances with or without the user’s knowledge, and polysubstance use (3–8). In addition, the availability of psychostimulants, particularly methamphetamine, appears to be increasing across most regions.**** In 2017, among drug products obtained by law enforcement that were submitted for laboratory testing, methamphetamine and cocaine were the most and third most frequently identified drugs, respectively.†††† Previous studies also found that heroin and synthetic opioids (e.g., illicitly-manufactured fentanyl) have contributed to increases in stimulant-involved deaths (3,9,10). Current findings further support that increases in stimulant-involved deaths are part of a growing polysubstance landscape. Although synthetic opioids appear to be driving much of the increase in cocaine-involved deaths, increases in psychostimulant-involved deaths have occurred largely without opioid co-involvement; however, recent data suggest increasing synthetic opioid involvement in these deaths.

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, at autopsy, substances tested for and circumstances under which tests are performed vary by time and jurisdiction. Therefore, recent improvements in toxicologic testing might account for some reported increases. Second, 15% and 12% of death certificates in 2016 and 2017, respectively, did not include mention of specific drugs involved. The percentage of death certificates with at least one drug specified varied widely by state, ranging from 54.7% to 99.3% in 2017, limiting comparisons across states. Third, potential racial misclassification might lead to underestimates for certain groups, primarily AI/AN and A/PI.§§§§ Finally, certain trend analyses were limited, given small numbers of deaths and the inability to calculate stable rates among some stimulant-opioid drug combinations before 2003.

Preliminary 2018 data indicate continued increases in drug overdose deaths.¶¶¶¶ The rise in deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants and the continuing evolution of the drug landscape indicate a need for a rapid, multifaceted, and broad approach that includes more timely and comprehensive surveillance efforts to inform tailored and effective prevention and response strategies. CDC currently funds 45 states and DC for opioid surveillance***** and/or prevention activities.††††† The contribution of opioids to increases in stimulant-involved overdose deaths underscores the importance of continued opioid overdose surveillance and prevention measures, including existing efforts to expand naloxone availability to persons at risk for drug overdose. CDC is expanding drug overdose surveillance efforts to include stimulants and is implementing multiple, evidence-based opioid prevention efforts, such as enhancing linkage to care, building state and local capacity, and public health/public safety collaborations.§§§§§ Because some stimulant deaths are also increasing without opioid co-involvement, prevention and response strategies need to evolve accordingly. Increased efforts are required to identify and improve access to care for persons using stimulants, implement upstream prevention efforts focusing on shared risk and protective factors that address substance use/misuse, and improve risk reduction messaging (e.g., not using alone). Continued collaborations among public health, public safety, and community partners are critical to understanding the local illicit drug supply and reducing risk as well as linking persons to medication-assisted treatment and risk-reduction services.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6817a3 ]

Corresponding authors: Mbabazi Kariisa, mkariisa@cdc.gov, 404-498-1560; Lawrence Scholl, lzi8@cdc.gov, 404-498-1489.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6817a3 ]

1Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6817a3 ]

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6817a3 ]

† https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm.

§ https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_public_use_data.htm.

¶ T40.0 (opium), T40.1 (heroin), T40.2 (natural/semisynthetic opioids), T40.3 (methadone), T40.4 (synthetic opioids other than methadone), and T40.6 (other and unspecified narcotics).

** A death involving both cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential (e.g., methamphetamine) would be included in both the cocaine and the psychostimulant with abuse potential death rates.

†† Age-adjusted death rates were calculated by applying age-specific death rates to the 2000 U.S. Census standard population age distribution https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_04.pdfpdf icon.

§§ Categories of 2013 NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm): Large central metro: Counties in metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) of ≥1 million population that 1) contain the entire population of largest principal city of the MSA, or 2) have their entire population contained in the largest principal city of the MSA, or 3) contain at least 250,000 inhabitants of any principal city of the MSA; Large fringe metro: Counties in MSAs of ≥1 million population that did not qualify as large central metro counties; Medium metro: Counties in MSAs of populations of 250,000–999,999; Small metro: Counties in MSAs of populations less than 250,000; Micropolitan (nonmetropolitan counties): counties in micropolitan statistical areas; Noncore (nonmetropolitan counties): nonmetropolitan counties that did not qualify as micropolitan.

¶¶ Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

*** State-level analyses comparing death rates from 2016 to 2017 included 34 states and DC that met the following criteria: 1) >80% of drug overdose death certificates named at least one specific drug in 2016 and 2017; 2) change from 2016 to 2017 in the percentage of death certificates reporting at least one specific drug was <10 percentage points; and 3) ≥20 deaths occurred during 2016 and 2017 in at least one drug category examined. States whose reporting of any specific drug or drugs involved in an overdose changed by ≥10 percentage points from 2016 to 2017 were excluded because drug-specific overdose numbers and rates might have changed substantially from 2016 to 2017 as a result of changes in reporting.

††† Z-tests were used if the number of deaths was ≥100, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Nonoverlapping confidence intervals based on the gamma method were used if the number of deaths was <100 in 2015 or 2016. Note that the method of comparing confidence intervals is a conservative method for statistical significance; caution should be observed when interpreting a nonsignificant difference when the lower and upper limits being compared overlap only slightly. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/NVSR/NVSR61/NVSR61_04.pdfpdf icon.

§§§ For all analyses, a p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/external icon.

¶¶¶ https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs38/38661/cocaine.htmexternal icon.

§§§§ https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_172.pdfpdf icon.

¶¶¶¶ https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm.

***** https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/foa/state-opioid-mm.html.

††††† https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/states/state_prevention.html; https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/foa/ddpi.html.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6817a3 ]

References

- Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA, Bacon S. Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants—United States, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:349–58. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1419–27. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Al-Tayyib A, Koester S, Langegger S, Raville L. Heroin and methamphetamine injection: an emerging drug use pattern. Subst Use Misuse 2017;52:1051–8. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- O’Donnell JK, Gladden RM, Seth P. Trends in deaths involving heroin and synthetic opioids excluding methadone, and law enforcement drug product reports, by Census region—United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:897–903. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths—27 states, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:837–43. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Somerville NJ, O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, et al. Characteristics of fentanyl overdose—Massachusetts, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:382–6. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Peterson AB, Gladden RM, Delcher C, et al. Increases in fentanyl-related overdose deaths—Florida and Ohio, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:844–9. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Mattson CL, O’Donnell J, Kariisa M, Seth P, Scholl L, Gladden RM. Opportunities to prevent overdose deaths involving prescription and illicit opioids—11 states, July 2016–June 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:945–51. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- McCall Jones C, Baldwin GT, Compton WM. Recent increases in cocaine-related overdose deaths and the role of opioids. Am J Public Health 2017;107:430–2. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Jones CM, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Changes in synthetic opioid involvement in drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2010–2016. JAMA 2018;319:1819–21. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

[ Top of page | Top of mm6817a3 ]

Source: National Vital Statistics System, Mortality File. https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

* Deaths are classified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD–10). Drug overdose deaths are identified using underlying cause-of-death codes X40–X44, X60–X64, X85, and Y10–Y14. Rates are age-adjusted using the direct method and the 2000 U.S. standard population, except for age-specific crude rates. All rates are per 100,000 population.

† Drug overdose deaths, as defined, that have cocaine (T40.5) as a contributing cause.

§ Drug overdose deaths, as defined, that have psychostimulants with abuse potential (T43.6) as a contributing cause.

¶ Categories of deaths are not exclusive because deaths might involve more than one drug. Summing of categories will result in more than the total number of deaths in a year.

** Drug overdose deaths, as defined, that have any opioid (T40.0–T40.4, and T40.6).

†† Data for Hispanic origin should be interpreted with caution; studies comparing Hispanic origin on death certificates and on census surveys have shown inconsistent reporting on Hispanic ethnicity. Potential race misclassification might lead to underestimates for certain categories, primarily American Indian/Alaska Native non-Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander non-Hispanic decedents. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_172.pdfpdf icon.

§§ By 2013 urbanization classification https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm.

¶¶ Analyses were limited to states meeting the following criteria: For states with very good to excellent reporting, ≥90% of drug overdose deaths mention at least one specific drug in 2016, with the change in drug overdose deaths mentions of at least one specific drug differing by <10 percentage points between 2016 and 2017. States with good reporting had 80% to <90% of drug overdose deaths mention of at least one specific drug in 2016, with the change in the percentage of drug overdose deaths mentioning at least one specific drug differing by <10 percentage points between 2016 and 2017. States included also were required to have stable rate estimates, based on ≥20 deaths, in at least one drug category (i.e., cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential) in both 2016 and 2017.

*** Absolute rate change is the difference between 2016 and 2017 rates. Percentage change (i.e., relative change) is the absolute rate change divided by the 2016 rate, multiplied by 100. Nonoverlapping confidence intervals based on the gamma method were used if the number of deaths was <100 in 2016 or 2017, and z-tests were used if the number of deaths was ≥100 in both 2016 and 2017. Note that the method of comparing confidence intervals is a conservative method for statistical significance; caution should be observed when interpreting a nonsignificant difference when the lower and upper limits being compared overlap only slightly. Confidence intervals for 2016 and 2017 rates of cocaine-involved deaths for Asian/Pacific Islanders overlapped only slightly: (0.35–0.54), (0.53–0.76) Confidence intervals of 2016 and 2017 rates of deaths involving psychostimulants with abuse potential for Virginia overlapped only slightly: (0.71–1.13), (1.10–1.60).

††† Statistically significant (p-value <0.05).

§§§ Data with <10 deaths are not reported. Rates based on <20 deaths are not considered reliable and not reported.

[ Top of page | Top of mm6817a3 ]

FIGURE 1. Age-adjusted rates* of drug overdose deaths† involving cocaine§ with and without synthetic opioids other than methadone (synthetic opioids) and any opioids¶ — United States, 2003–2017**,††